Custom-built trilingual New Testament

Custom-built trilingual New Testament

I'LL JUST MAKE IT MYSELF

THE FIRST PRINTED GREEK-LATIN-ENGLISH NEW TESTAMENT (IN A MANNER OF SPEAKING)

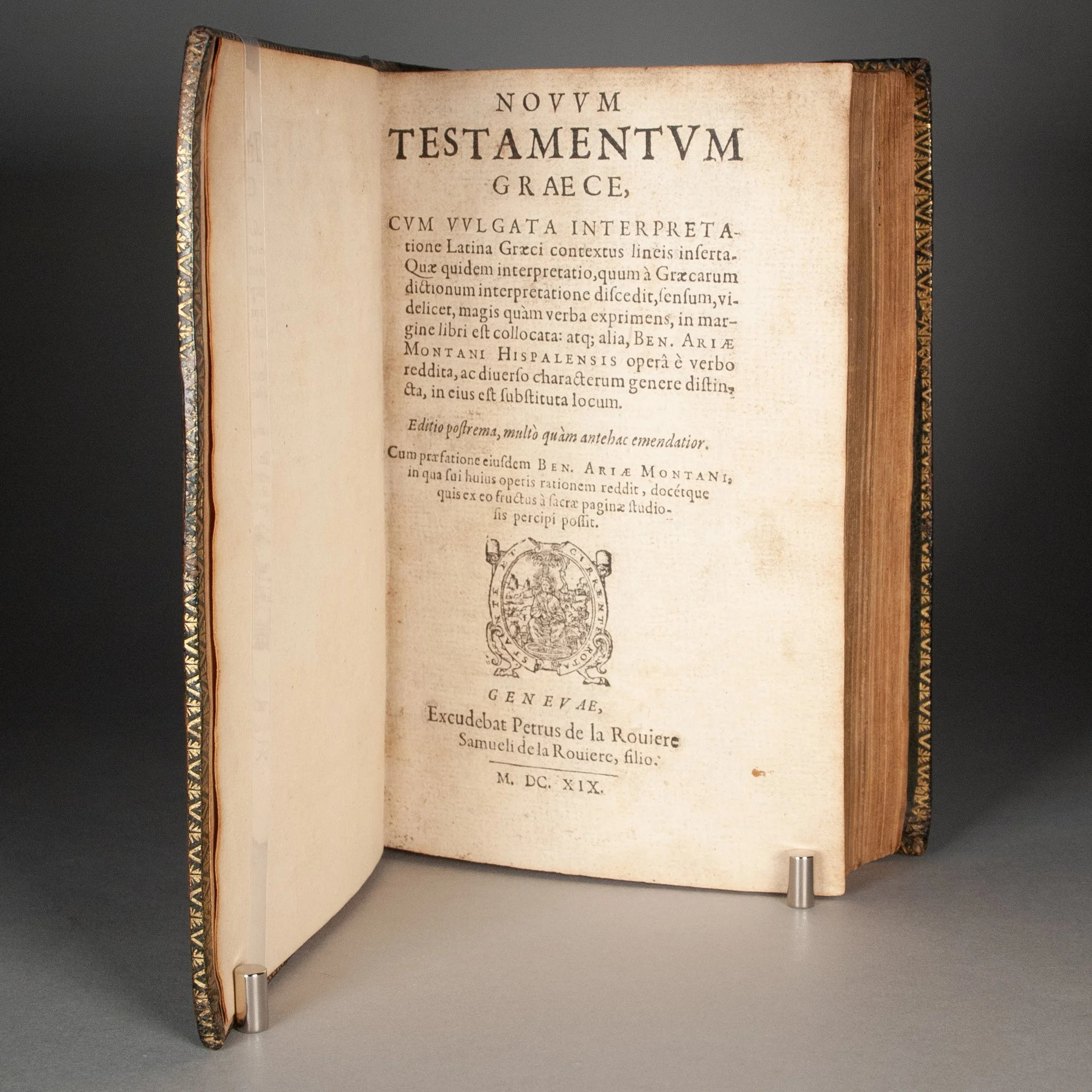

[Custom trilingual New Testament assembled from] Novum Testamentum Graece cum vulgata interpretatione Latina Graeci contextus lineis insertaquae quidem interpretatio [and an unidentified edition of the King James Version]

2 volumes | 8vo | 191 x 120 mm

Novum Testamentum Graece, cum vulgata interpretatione Latina Graeci contextus lineis insertaquae quidem interpretatio…Ben. Ariae Montani Hispalensis operâ è verbo reddita, ac diverso characterum genere distincta, in eius est substituta locum; editio postrema, multò quàm antehac emendatior…

edited and translated by Benito Arias Montano

Geneva: Pierre de La Rovière, 1619

[16], 1082, [2] p. | ¶^8 A-3X^8 3Y^6

bound with

[Unidentified edition of the King James New Testament]

[England, 18th century]

[332] p. | A^8(-A1) B^8(-B8) C-X^8 (lacking the title leaf and B8 at least)

A powerful example of one owner’s meddling enterprise to create, from two separately published books, a single book that did not exist. The owner has reassembled an early New Testament in Greek and Latin with an 18th-century edition of the King James Version to create his own trilingual edition. For no more cost, he could have bound the two works separately. They could have sat right next to each other on the shelf, their individual integrity intact. But as the spine title makes clear—Testameutum Trilingue—this owner didn’t want a separate Greek-Latin New Testament and a separate English New Testament. He wanted a trilingual New Testament as a single work. In this case, v. 1 contains the Four Gospels, the English text bound after the Greek and Latin; v. 2 contains the remainder of the New Testament, English again following the Greek and Latin. ¶ This is not simply the composite volume of convenience we see with Sammelbände, several thematically similar texts bound together to economize on binding costs. Nor is it the kind of relatively minor shuffling we might see in such volumes—for example, when the index for the first work might be relocated to the very end of the composite volume. This is the case of someone wanting a specific book, one that had never been published, and creating it for himself from two existing books. To be sure, British publishers had produced plenty of polyglot Bibles. London issued the last of the great polyglots in 1653-1657, final heir of the Complutensian spirit, with English alongside a variety of ancient biblical languages. In the 1710s and 1720s, James Knapton published a series of individual Bible books in Greek and English. Quite a variety of language combinations were available. But according to ESTC, this particular combination—the New Testament in Latin, Greek, and English—had not yet been published. The only biblical text in Latin, Greek, and English that ESTC records is a 1736 selections from the Old Testament (ESTC T139728). ¶ When choosing his Greek-Latin edition, our owner could have done worse. Montano’s has an august history, the work of “the most important Spanish Bible scholar” (Mediano). He prepared it for Plantin’s massive polyglot edition of 1568-1573. Indeed, the King of Spain, who financed the project—if reluctantly, nearly bankrupting Plantin—sent Montano to Antwerp to oversee the entire project. Establishing an accurate New Testament was no small matter. “No other text posed the problem of the Textus Receptus or lectio recepta in so stark a form; and no other text was necessary to salvation. The character of the vulgate established by Erasmus, Beza and Stephanus was so obviously haphazard that thoughtful critics, in countries where it was allowable to do so, had the strongest incentives for questioning its authenticity” (Kenney). Backed by Catholic financing from a Catholic monarch, it’s perhaps unsurprising that Montano’s text found little room on English presses—even if his interpretive work later landed him on the Catholic Index of Prohibited Books—rendering our owner’s juxtaposition with the King James Version all the more striking. ¶ A remarkable case of textual intervention and repackaging, and a relatively late example of a practice we tend to associate with the earlier days of print. Even three centuries after European invention of the press, such meddling spirit endured.

PROVENANCE: Almost certainly assembled by John Shaw (1750-1824), Greek scholar at Magdalen College, Oxford. His ownership inscription has been mostly obliterated from the front paste-down—Johannis Shaw remains legible enough—but a later inscription on the fly-leaf reports more thoroughly: “Jan. 21, 1824. Presented to me by Joseph Parkinson Esq. one of the executors of Dr. John Shaw, Fellow of Magd. Coll. Oxford, who died on Jan. 14, 1824.” It’s satisfying provenance in this case, a trilingual creation by someone with a serious interest in Greek. Sadly, despite his Oxford credentials and a published edition of Apollonius Rhodius to his name, Shaw was not the most critically acclaimed Hellenist. “Shaw’s Apollonius passed into legend,” and not for good reasons. His continental colleagues were searing. “Daniel Wyttenbach’s review of Shaw in Bibliotheca critica was more elegantly brutal: if, he observed, one were to judge an edition by the elegance of its paper and typefaces, Shaw’s Apollonius would be among the best of its kind; but if one judges it by what it can contribute towards an understanding of the author, it would be generous even to place it among the mediocre.” The Clarendon Press had hoped for strong sales. “After such a critical pasting, however, it is not surprising that by 1804 over two-thirds of the copies remained unsold. As for Shaw himself, he never dared to venture into print again” (Darwall-Smith). Perhaps this bespoke New Testament was the closest he got to producing a new book. ¶ Earlier armorial bookplate on title verso of Peter Killigrew of Arwenack in Cornwall, Knight and Baronet, though we struggle to identify precisely which man this refers to: the 2nd baronet (ca. 1634-1705) or his father (ca. 1593-1668). It seems the style could fit the time period of either one, based on W.J. Hardy’s Book-Plates and James P. Keenan’s Art of the Bookplate. ¶ Some early inked marginal markings in the English text. Penciled ownership inscription on v. 1 fly-leaf of Oxford scholar Eric Jacobsen, 1940s. Bookseller’s ticket on both front paste-downs of Thornton & Son, Oxford.

CONDITION: Eighteenth-century dark morocco, richly tooled in gold, Oxford work, we should think; edges gilt. Some endleaves and blank inserts with a Vryheyt watermark, best visible where the English text lacks leaf B8. Save for this single leaf from the Gospel of St. Matthew, the English New Testament is textually complete. We suspect Shaw used a defective copy—note some tears in its early leaves—and perhaps intended to transcribe the missing text on these two blank leaves inserted where B8 should be. ¶ Closely cropped, shaving some headlines in both texts, and some text at the fore-margin of the English portion; scattered ink stains and light soiling; some scattered marginal tears; title moderately soiled, and occasional foxing. Some light rubbing to the extremities, and the spine of v. 1 a little cocked, but the bindings really look very nice.

REFERENCES: USTC 6702521 and 6702506 (for the Montano New Testament, by all appearances the same book) ¶ E.J. Kenney, The Classical Text: Aspects of Editing in the Age of the Printed Book (Univ of Calif, 1974), p. 99; James Raven and Goran Proot, “Renaissance and Reformation,” The Oxford Illustrated History of the Book (OUP, 2020), p. 165 (on translating the Bible: “Textual differences were often minute, but as daunting and high-profile claims about printed variants ensured, tiny differences in translation and emphasis supported momentous doctrinal dispute.”); Fernando Rodríguez Mediano, “Biblical Translations and Literalness in Early Modern Spain,” After Conversion: Iberia and the Emergence of Modernity (Brill, 2016), p. 84 (cited above); Jeffrey Todd Knight, Bound to Read: Compilations, Collections, and the Making of Renaissance Literature (UPenn, 2013), p. 8 (on earlier interventions, but here the spirit continues: “The readers and writers of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries did not simply think of their books as aggregations of text; they physically aggregated, resituated, and customized them. Out of necessity and desire, they assembled volumes into unique configurations and built new works out of old ones. Models of literary production in the period were perhaps to a surprising degree predicated on the possibility that a text could be taken up and joined to something else.”); Robin Darwall-Smith, “In the Centre and on the Periphery: The Paradox of Classics in Georgian Oxford,” History of Universities, v. XXXV/1 (Oxford Univ, 2022), p. 57-58

Item #689