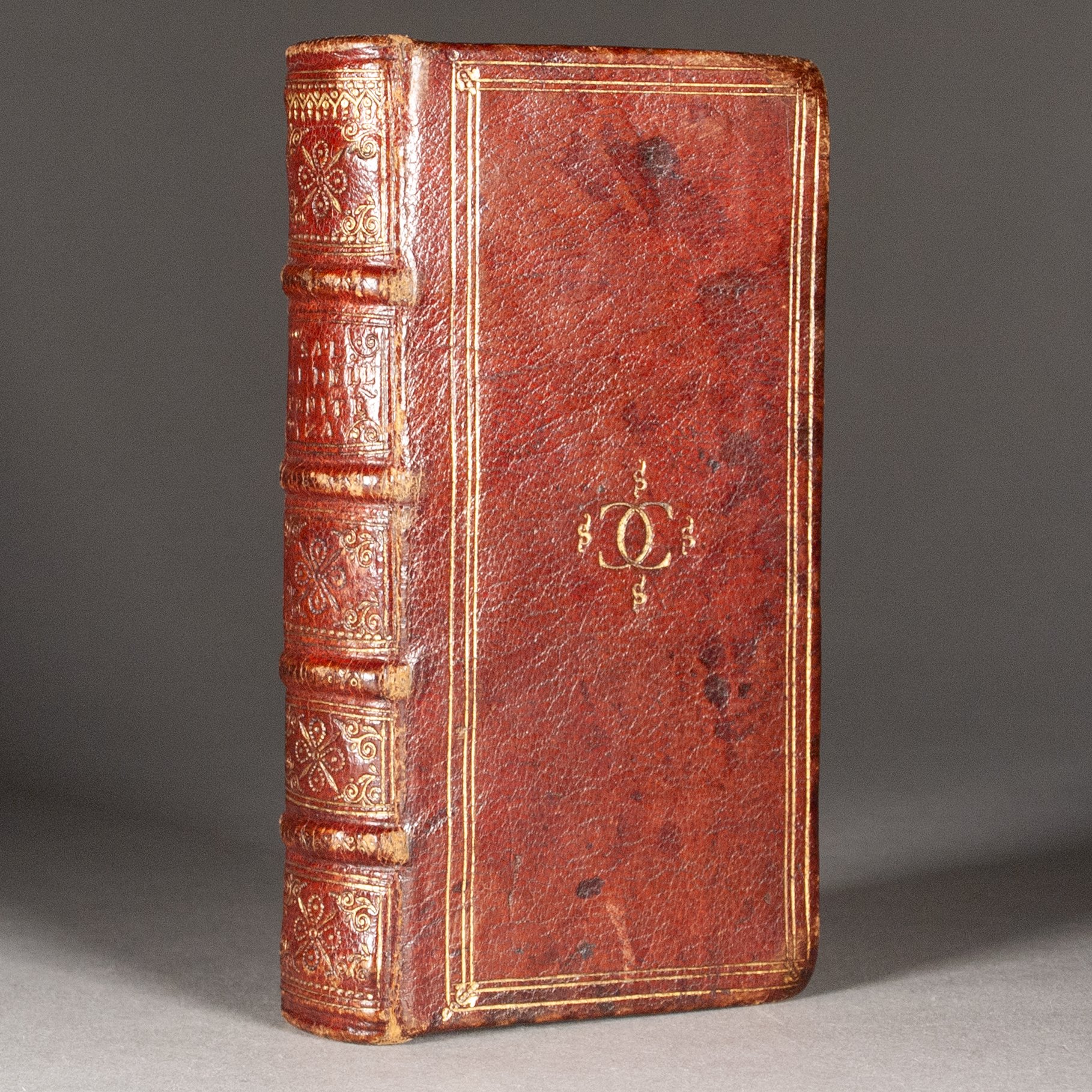

Vicious Italian's banned books abroad | French S-fermé binding

Vicious Italian's banned books abroad | French S-fermé binding

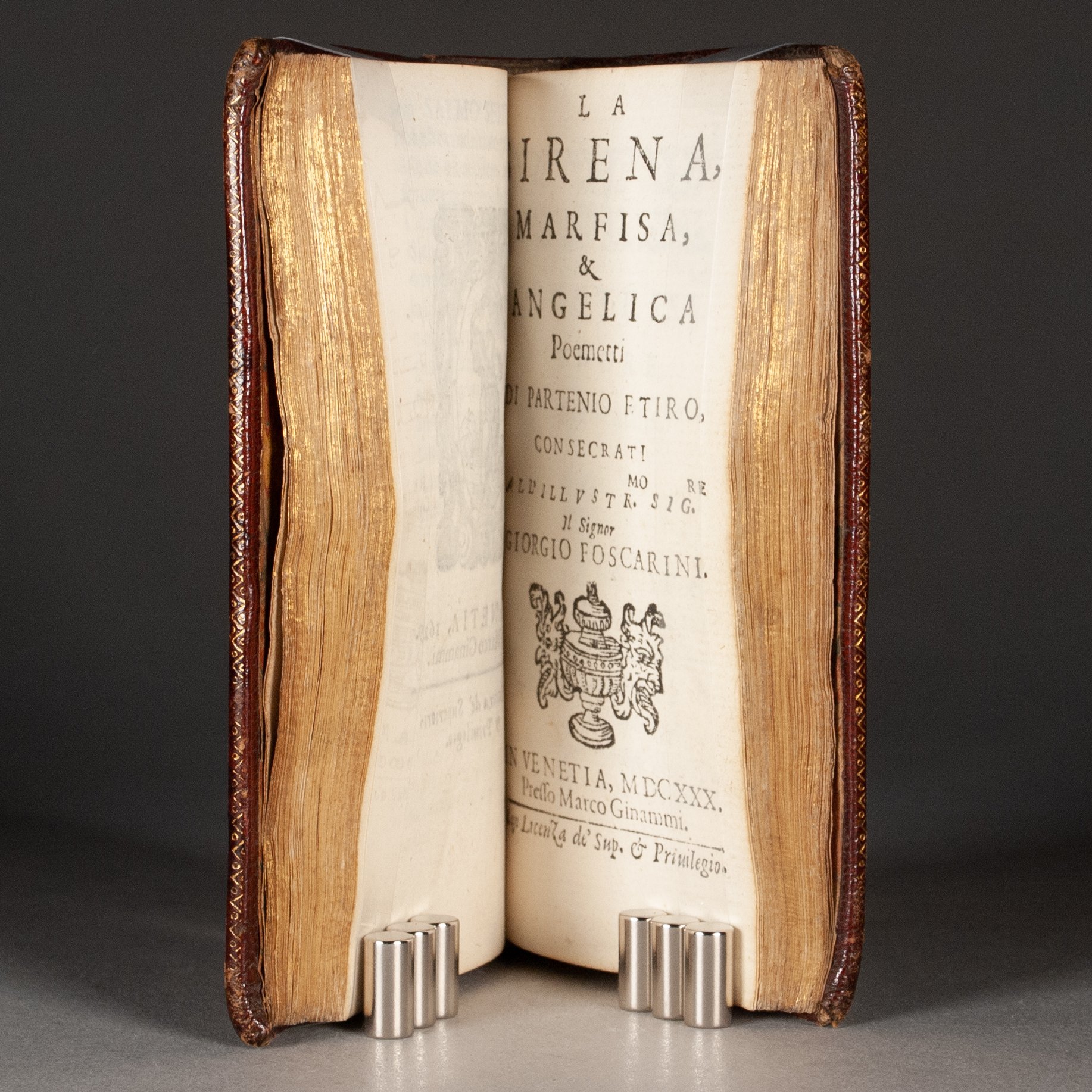

Parafrasi sopra i sette salmi della penitenza di David de Partenio Etiro [bound with] La sirena Marfisa & Angelica poemetti di Partenio Etiro

by Pietro Aretino

Venice: Marco Ginammi, 1629 and 1630

202, [2]; 168 p. | 24mo | A-H^12 I^6; A-G^12 | 121 x 60 mm

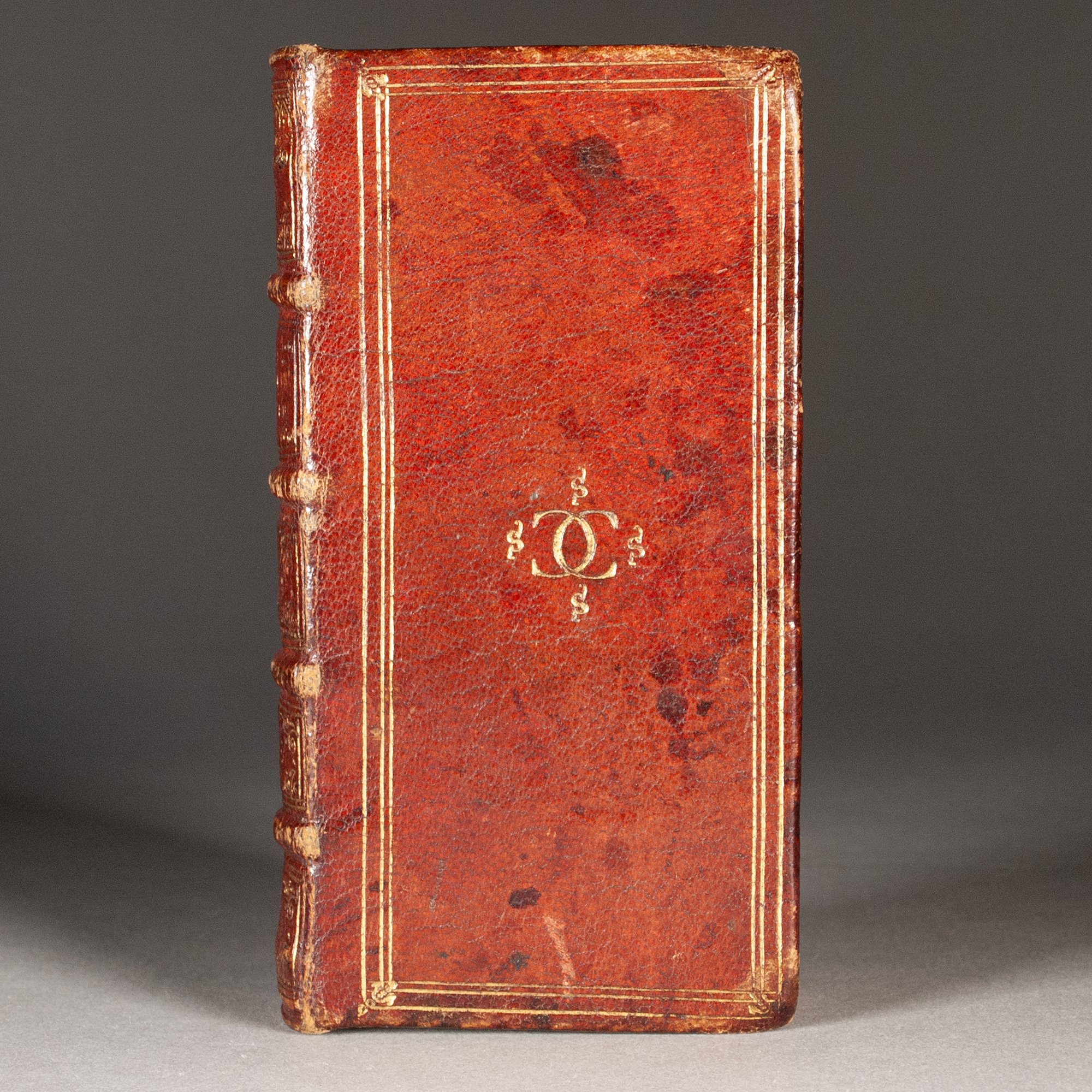

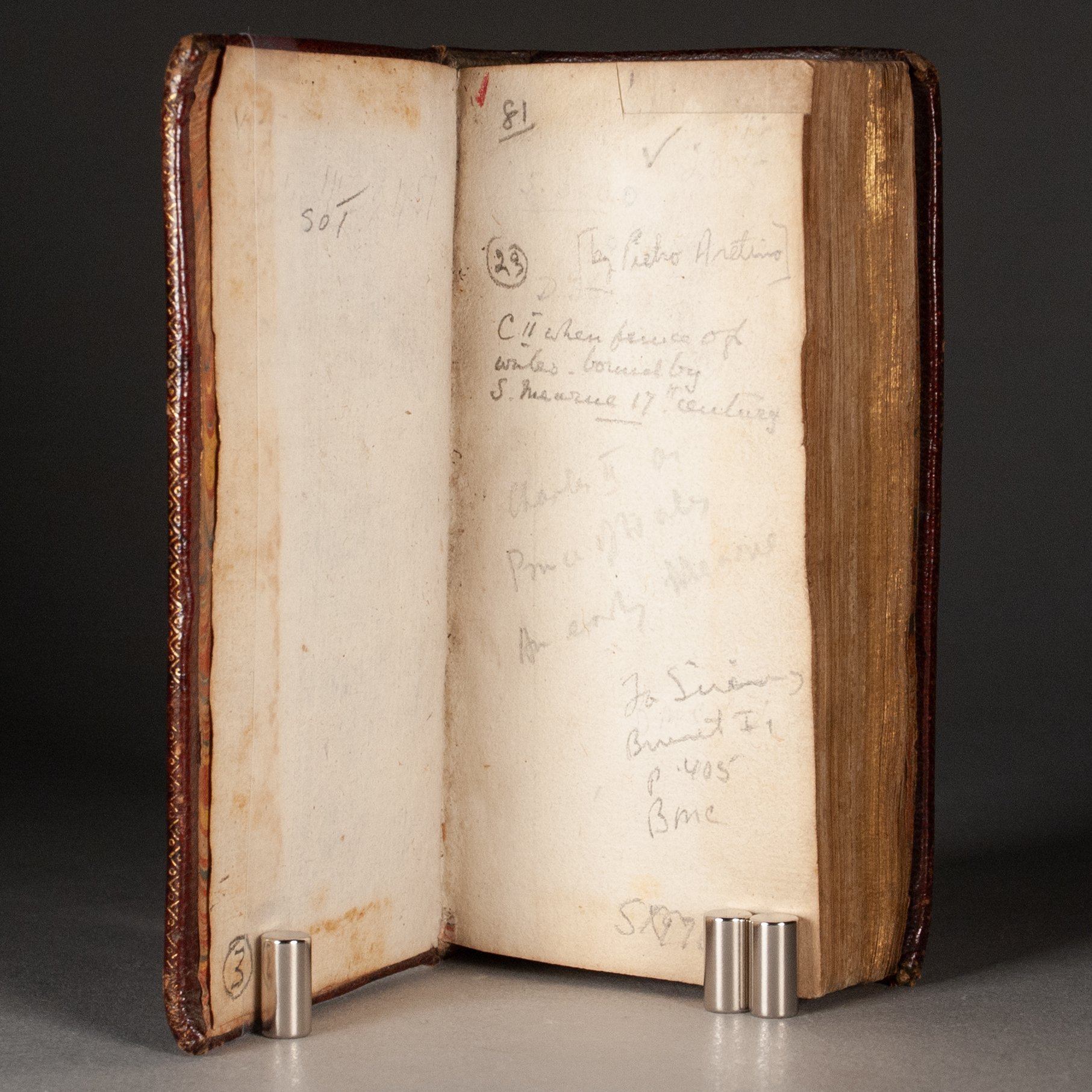

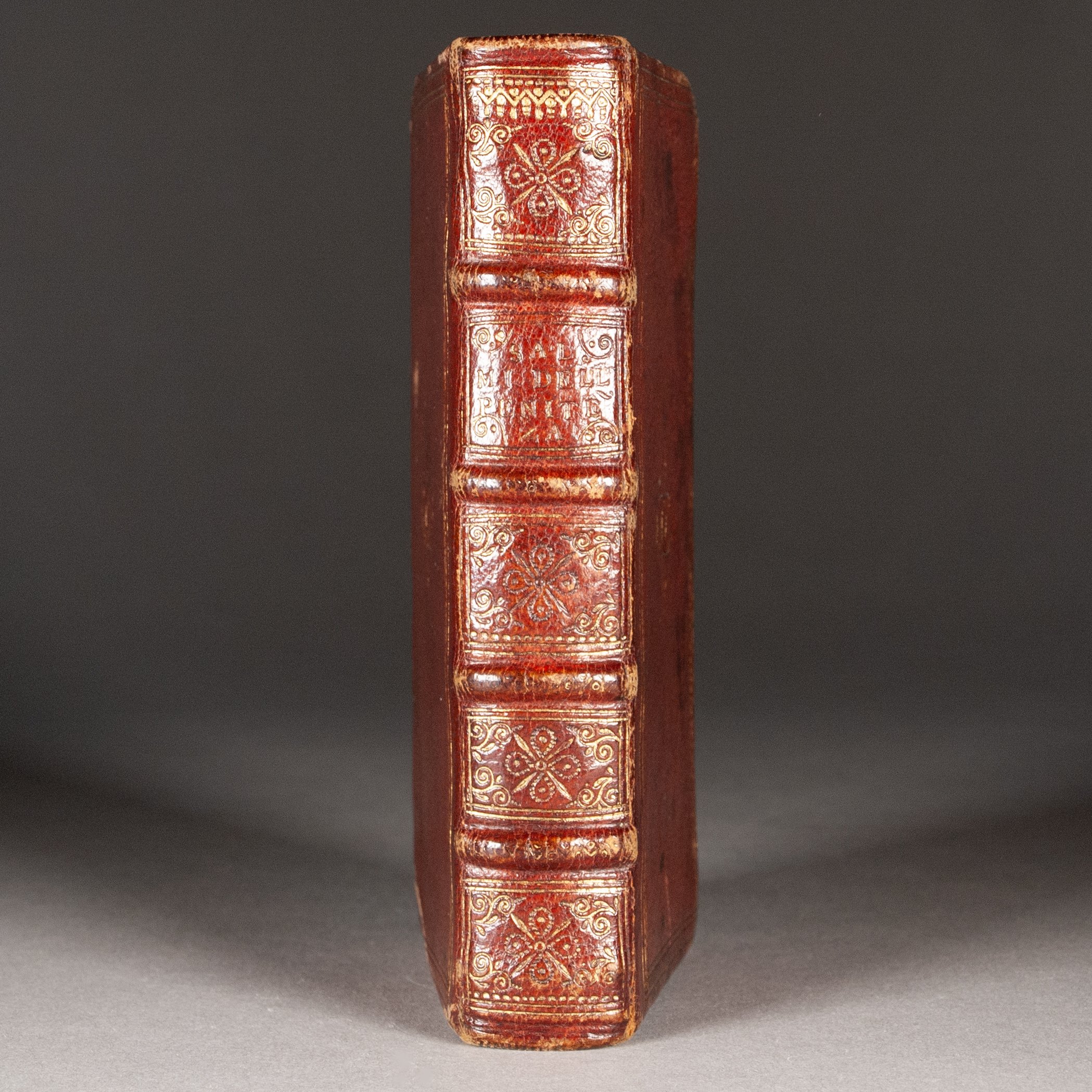

A later edition of Aretino's Sette salmi, first published in 1534, here bound with a combined edition of three other Aretino poems: Stanze in lode di Madonna Angela Sirena (1537), Marfisa (1535), and D'Angelica (1535). Aretino was a vicious writer, "perhaps the most gifted satirist, pornographer and literary blackmailer of any age" (Steinberg), and responsible for some of "the earliest notorious sexual writings in the vernacular" (Crawford). He allegedly drove one target of his pen to suicide. While Aretino would not have called himself a Protestant, he was in favor of reforming the Church. Given his output, reputation, and confessional ambiguity, it may come as no surprise that the Catholic Church banned his entire corpus in its inaugural Index Librorum Prohibitorum. That ban remained in effect when our editions were published. Even this seemingly innocuous Italian rendition of the Penitential Psalms exhibited dubious influence. Thomas Wyatt's English (and rather more Protestant) version is little more than a translation of Aretino's. For all that, our printer, Marco Ginammi, here dedicated his edition of the Sette Salmi to a Sister Cornelia in the local San Girolamo monastery. ¶ At the time our editions were published, the Republic of Venice was making it difficult for the Vatican to enforce its book bans. Ginammi took good advantage of this period of reduced Roman surveillance. His thinly veiled pseudonym for Aretino must have been his own invention, as we find it only on his editions. On the surface, it's an absurdly simplistic attempt to evade inquisitorial discipline, but perhaps that was the joke. "Ginammi probably mocked a powerless Holy Office with these transparent anagrammatic pseudonyms" (Grendler). Obstructed in Venice, the Inquisition tried to contain the problem. "Unable to halt the traffic into Venice or to take effective action against the local bookmen, Rome could only try to stop the distribution of banned works elsewhere" (Grendler). At least in this case, as in so many others, that effort failed. Here in a contemporary French binding, our copy is a plain reminder of Rome's repeated failure to police both local production and international distribution of illicit material. ¶ In a well preserved and eminently French contemporary binding, done in the s fermé style popular during the later years of the 16th century and first half of the next. Its hallmark is the peculiar S with a line through it, a rendition of the letter's gothic ancestor. It was a thoroughly French emblem, used not just on bindings but across media. Individuals commonly combined it with their signatures on documents, for example, on account of which it's thought to have taken on the symbolic meaning of a personal seal (S for sigillum), and by extension an emphasis of ownership in contexts like this. In time, it came to signify loyalty or fidelity, virtues that were broadly interpreted—fidelity to one's faith, to one's lover, etc. Lavish semé bindings sometimes blanket their covers with repeating monograms and s fermés, but they more commonly manifest like ours:four s fermés surrounding a monogram. ¶ Penciled notes on the front fly-leaf (and a relatively recent bookseller's description) call this an early binding by Samuel Mearne, widely considered 17th-century England's greatest binder. The assertion presents a rather romantic origin story, but one worth exploring, if only because the notes there scribbled will likely endure as an elephant in the room. Mearne did produce bindings for Charles II tooled with an interlocking double C cipher much like this. However, his cipher was typically positioned in the corners of the boards or on the spine, not in the center of the board, and it was invariably surmounted by a crown. Such bindings date from 1660, following the Restoration of Charles II. Just prior to that, in the late 1650s, during those final years of the Commonwealth, Charles II and Samuel Mearne were in Holland at the same time. "Though we have at present no direct evidence of the fact, it appears probable that Mearne was employed in some capacity by Charles, and did some services for him, otherwise there would be no reason for his receiving a court appointment immediately on Charles' restoration" (Duff). ¶ The theory, then, is that Mearne made this binding for Charles II during those later Interregnum years, before his restoration, hence the absence of the crown above the cipher. In that case, beyond their more established meanings, we suppose the S's might also stand for the House of Stuart. It all sounds plausible enough, but Charles II was hardly the only person to use the interlaced double C cipher (Coco Chanel, anyone?), nor was he even the first to surmount it with a crown. Charles IX of France did so a full century earlier. In addition to Charles IX, we find the interlocking double C cipher also used by the Comte Charles de Mansfelt, and especially by Catherine of Bourbon. All this to say, unless more compelling evidence comes to light, we'll assign this binding to Mearne's apocrypha.

PROVENANCE: The s fermé binding was a favorite style of the Bourbons, used by at least three generations of the family. Rather than Charles II, then, we'd start with members of the Bourbon family whose dates can be reconciled with our imprints. In addition to Catherine, Christine Marie de France and husband Victor Amadeus used a cipher of their combined initials on some of their books, Christine's share represented by a pair of interlaced C's.

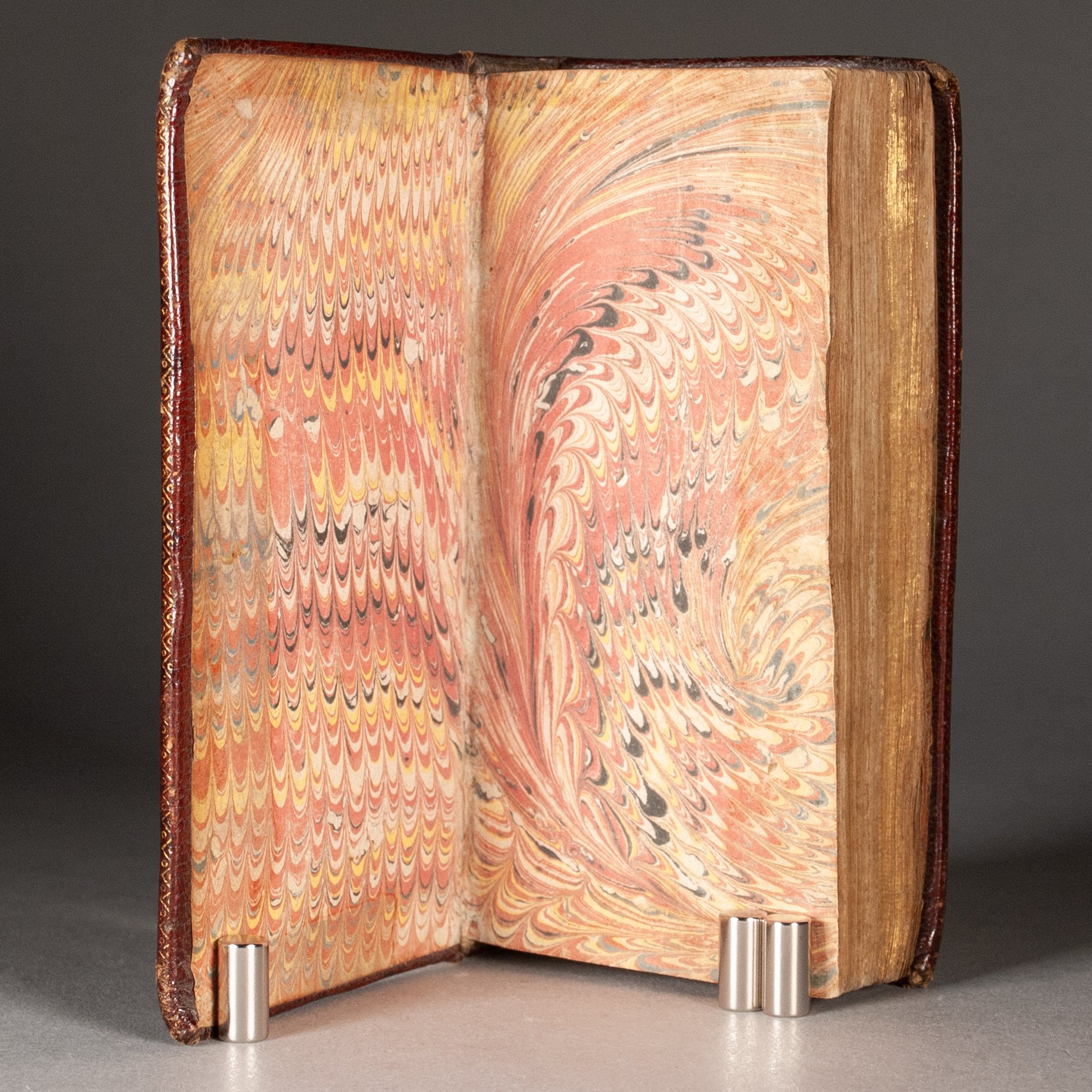

CONDITION: Contemporary French reddish-brown goatskin tooled in gold, the spine with quatrefoil and small vine tools; edges gilt and marbled endpapers. Our marbled endpapers, too, are not unlike the small comb pattern found on a 1627 Paris imprint (see Wolfe). ¶ Small 1 cm closed tear in the first title leaf, not affecting text; upper corner of C1 in Marfisa clipped, affecting the page number. Extremities just gently bumped and worn; upper corner of front fly-leaf excised. Really a handsome, well preserved book.

REFERENCES: USTC 4008281, 4008784 ¶ On the content: Paul F. Grendler, The Roman Inquisition and the Venetian Press, 1540-1605 (1977), p. 284 (cited above), 285 (cited above; "Marco Ginammi, a prominent publisher, flaunted the Index by printing Machiavelli and Aretino"); S.H. Steinberg, Five Hundred Years of Printing (1996), p. 35 (cited above); Katherine Crawford, European Sexualities, 1400-1800 (2007), p. 218 (cited above); William T. Rossiter, "What Wyatt Really Did to Aretino's Sette Salmi," Renaissance Studies 29.4 (Sept 2015), throughout (a good exploration of Aretino's Salmi vis-à-vis Wyatt's translation) ¶ On the binding: Geoffrey D. Hobson, Les reliures à la fanfare; Le problème de l'S fermé (1970), p. 88-89 (the s fermé used in letters), 97 ("was almost entirely the preserve of the French"; most of the few documented examples that belonged to foreigners were likely made in France), 101 (the s fermé surrounding initials was "the most common arrangement"), 102 (on its use like a seal, reinforcing ownership), 106 ("without a doubt, then, the S often signifies constancy in love, or rather fidelity in general"), 111 ("the S was almost exclusively French and was mostly in use between 1580 and 1640, and I believe both of these assertions are correct"), 115 ("it was an emblem of the Bourbons...The letter was used by at least three generations of the Albret-Bourbon family"); Martin Breslauer Inc., Catalogue 103, #38, color plate XI (a binding for Catherine of Bourbon; she "was one of the first to employ the 'closed S' in France, a symbol signifying 'fermesse' and 'fidelité'—in her case fidelity to the Protestant religion"); Maggs Bros. Ltd., Bookbinding in the British Isles...Catalogue 1075 (1987), pt. 1, #47 (a late 16c Parisian binding with a monogram surrounded by four s fermés, this one for English owners; "The 'S fermé' was used extensively in France from the early sixteenth century as a symbol signifying 'fermesse' or loyalty. Apart from bindings it can be found written in books, on letters, and incorporated into embroideries, but it does not appear to have been used at all in England."); Paul Culot, "La reliure en France au XVIe siecle," Italian and French 16th-century Bookbindings (1991), #69 (ca. 1595-1600 French vellum binding with a central monogram surrounded by four s fermés); Bibliothèque de Mme Th. Belin: précieux manuscrits...riches reliures anciennes armoriées (1936), #100, plate XXXVII (a late 16c French fanfare binding with a monogram surrounded by four s fermés); H. George Fletcher, Judging a Book by Its Cover (2023), #3.6 (ca. 1626 French binding with a monogram surrounded by four s fermés); Léon Gruel, Manuel historique et bibliographique de l'amateur de reliures (1887-1905), v. 1, facing p. 24 (reproduction of Charles IX's crowned cipher), facing 134 (reproduction of a binding for Comte Charles de Mansfelt using another interlaced double C monogram); Richard J. Wolfe, Marbled Paper (2018), plate XV.3 (a French small comb pattern using a color palette similar to ours), p. 62 ("there is little evidence that marbling was attempted in Great Britain in the seventeenth century except on an experimental or trial basis"); Hugh Davies, Catalogue of a Collection of Early French Books in the Library of C. Fairfax Murray (1910), v. 1, p. 166, #170 (facing plate pictures a binding with Christine de France and Victor Amadeus's cipher) ¶ On Samuel Mearne: E. Gordon Duff, "The Great Mearne Myth," Papers of the Edinburgh Bibliographical Society 1912-1920 (1921), p. 48 (cited above); Howard M. Nixon, English Restoration Bookbindings (1974), p. 12-13 (summary of Mearne's usual royal binding styles)

Item #828