Children's board book

Children's board book

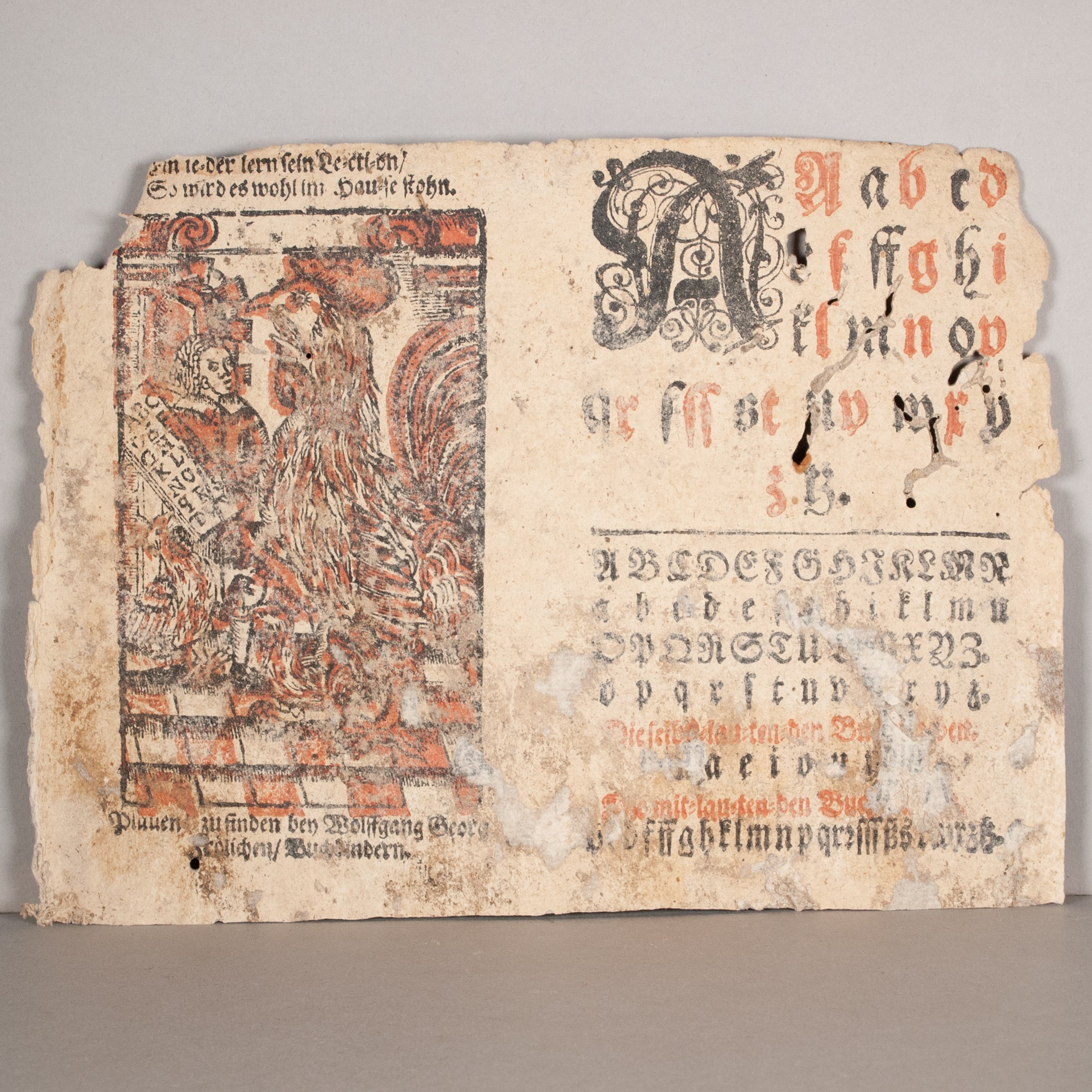

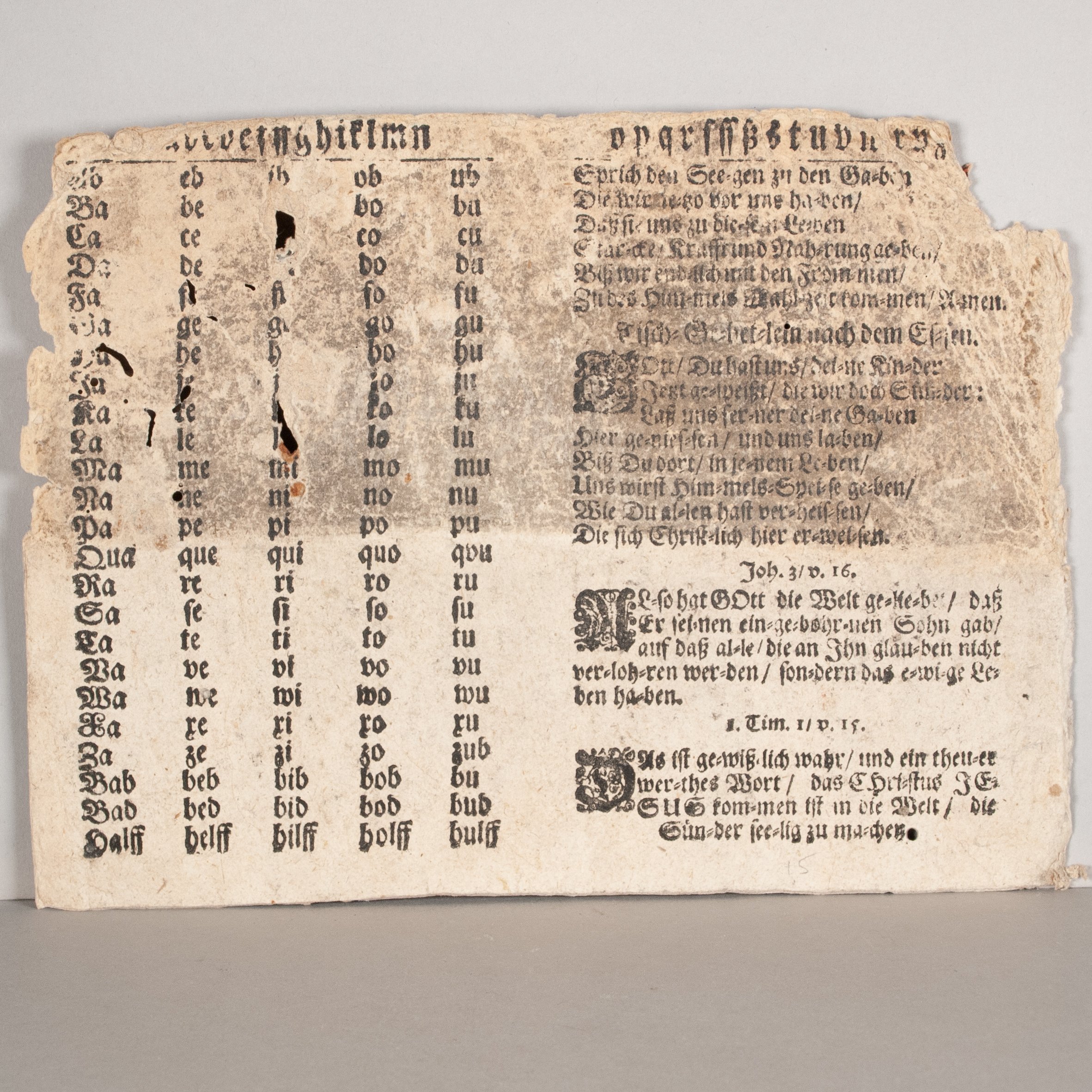

A a a b c d... [ABC Buchlein | ABC Book]

Plauen: Wolffgang Georg Fröhlich, [18th century?]

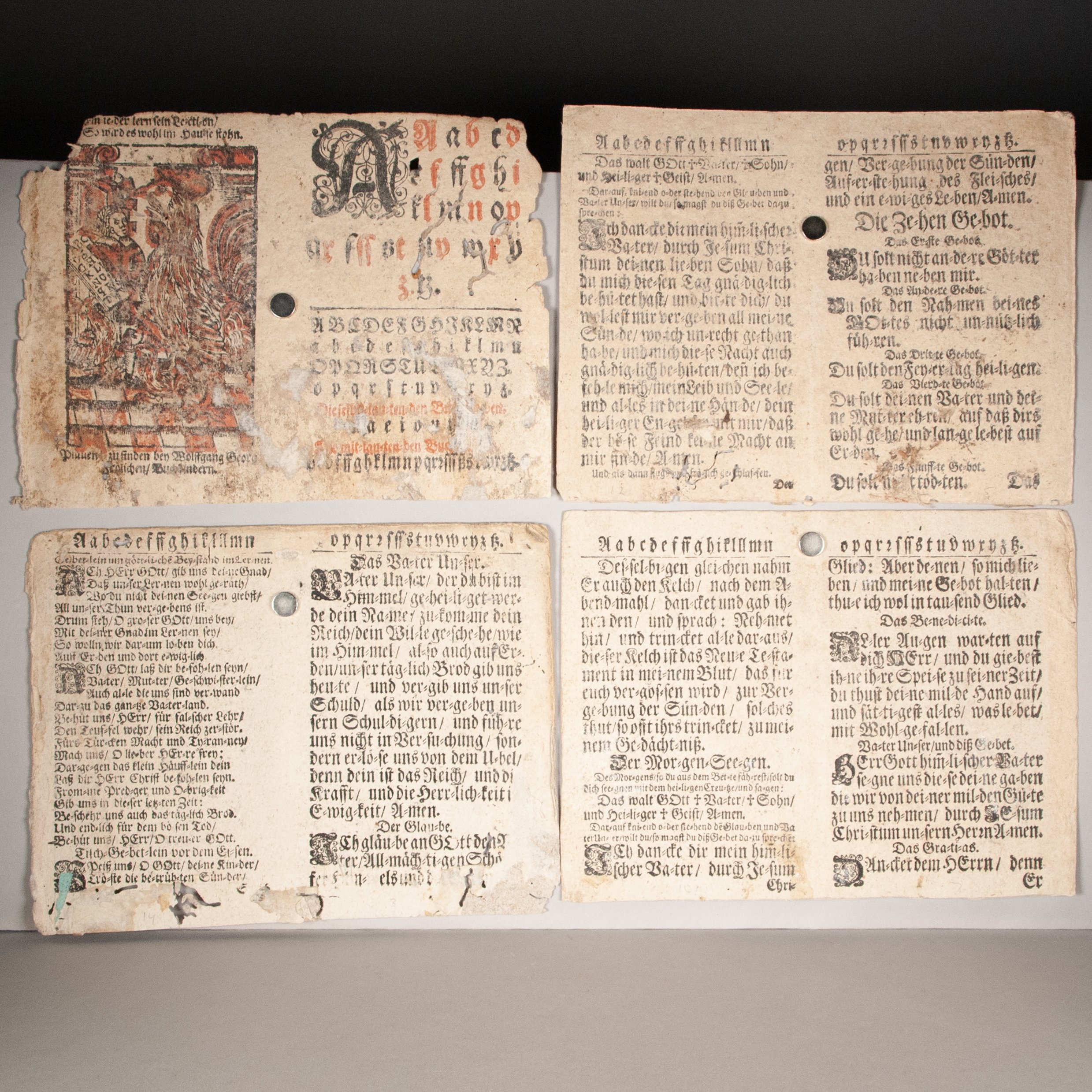

[16] p. | 8vo | [A]^8 | 157 x 204 mm (as bifolia)

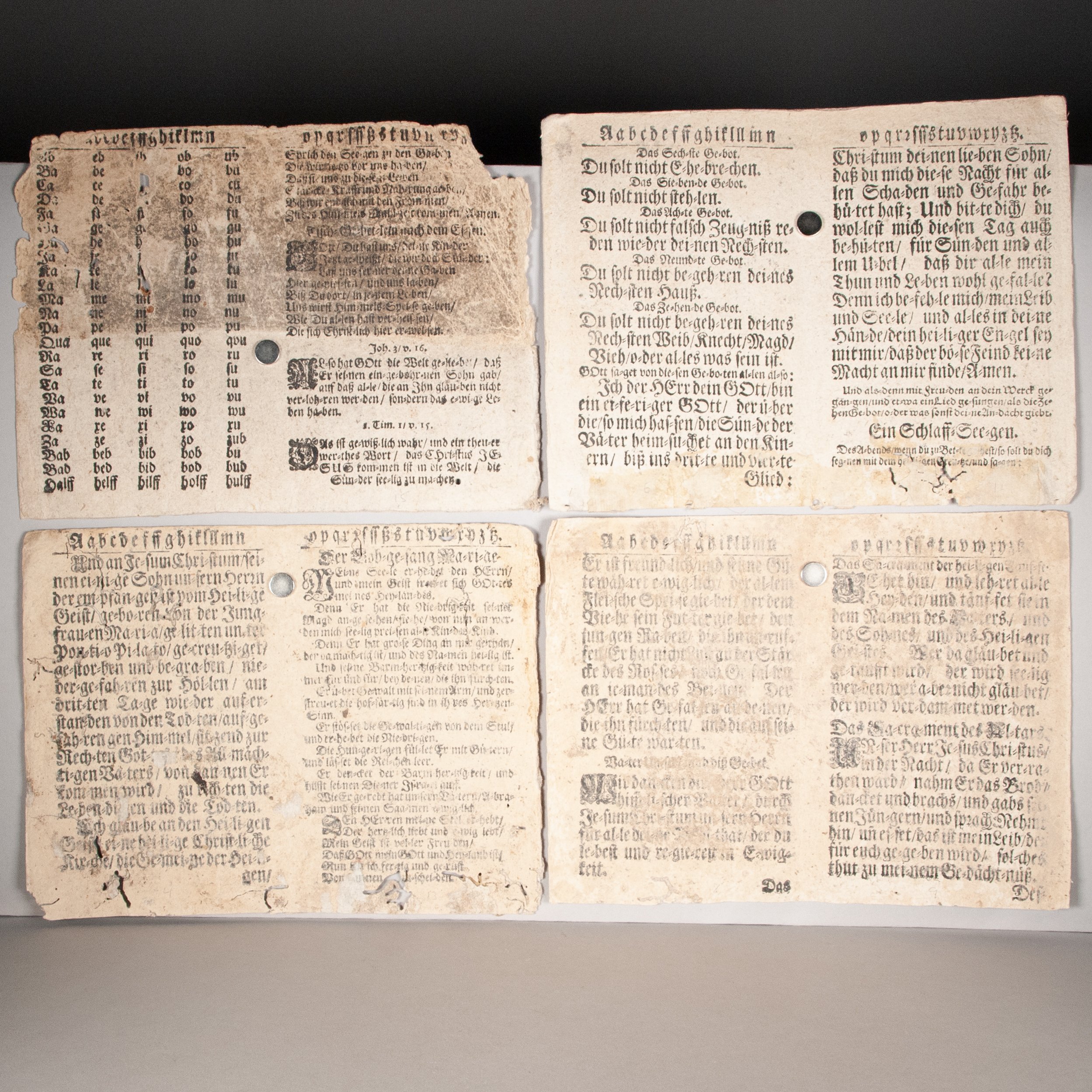

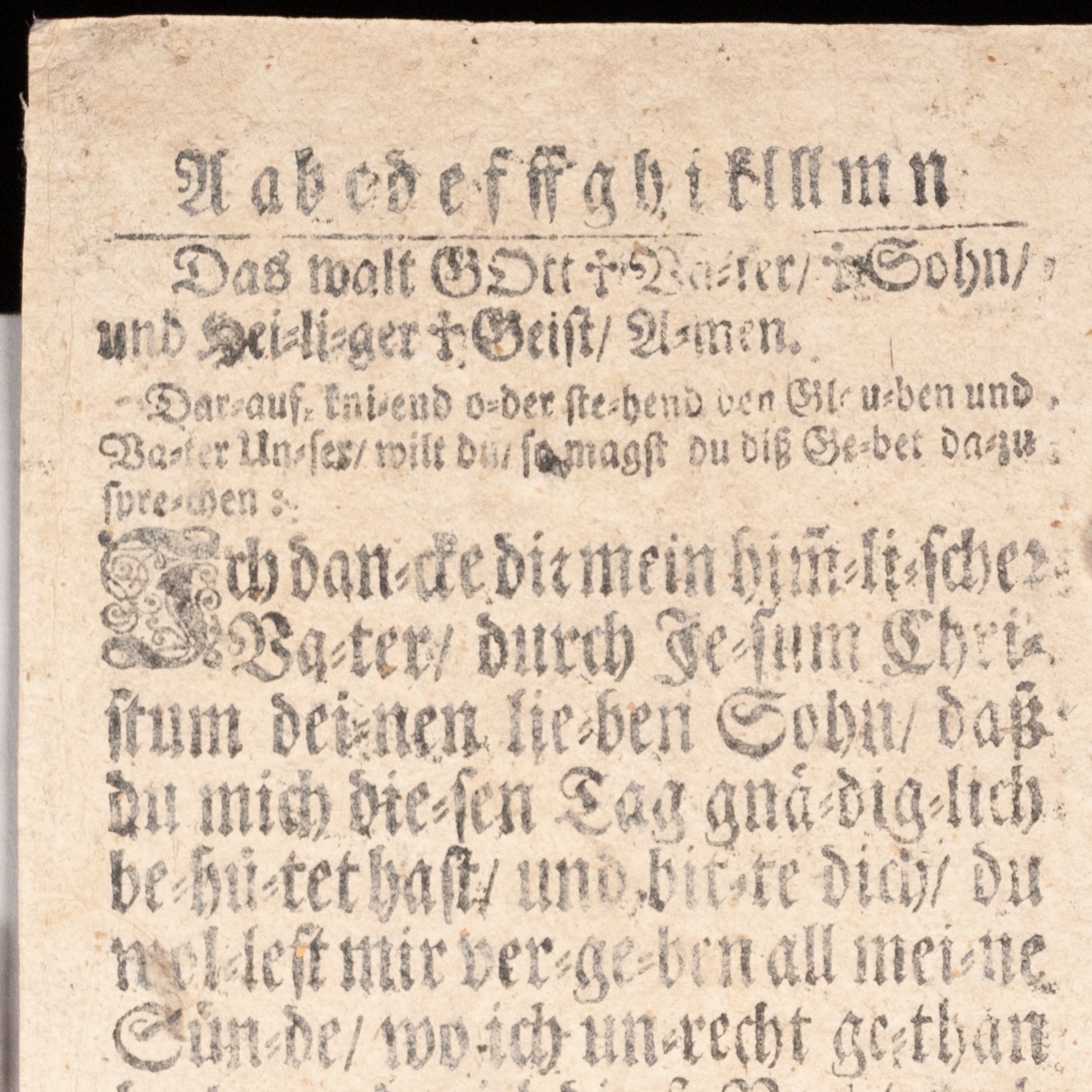

An astonishing example of an 18th-century children's primer printed entirely on thin pasteboard. While not quite as sturdy as the pages of today’s board book, the intent was no doubt the same: to provide a durable book that could better withstand the rough handling of children. It’s an enchanting object, something that calls to mind a more evolved, multi-page hornbook—which was, after all, the original durable print for learning the alphabet. The layout of our title readily calls to mind that captivating educational tool. The second page contains a syllabary, and the third page the Lord’s Prayer, both of which became common hornbook features. Remaining space is here filled with German prayers, each word hyphenated syllabically to facilitate learning. A complete alphabet runs across the top of every two-page spread, and the closing page contains a large woodcut of a rooster instructing a young student with a hornbook. We suspect this illustration was inspired by the wildly popular Dutch Haneboek, named after the cock woodcut found on the title page of so many editions, and which became popular after the Synod of Dort (1618-1619) insisted that children’s primers be based upon it. ¶ Despite the colophon, we've been unable to trace our publisher: Wolffgang Georg Fröhlich, a bookbinder in Plauen, Germany. While our Frölich could admittedly have commissioned this from a printer outside his own friendly confines, it’s worth noting that Plauen didn’t have its own press until 1670, so we’re disinclined to date our little primer before the late 17th century. The layout of our title and the illustrated final page are hallmarks of the 18th-century editions we’ve seen, while 17th-century editions we’ve encountered generally have simpler title pages. That said, the Cotsen Collection contains a strikingly similar Halle edition dated 1703, with a red and black ABC title and full-page rooster above the colophon on the final page, so we wouldn't rule out the possibility of late-17th-century production. See also a Leipzig edition by Friedrich Köhl, with which our edition has textual and typographic parallels throughout, again with a strikingly similar black-and-red rooster woodcut on the final page. BSB catalogers date this Köhl edition between 1728 and 1777, a range we can perhaps narrow slightly: Köhl didn't take over Justus Reinhold's press until 1731; and after 1763, his imprints may have been more likely to include the name of his partner and son-in-law, Christian Philipp Dürr, who succeeded him in 1771. For other similar editions, see VD17 14:680954H, ca. 1700, again with similar title layout, textual content, and large rooster woodcut on the final page; and lot 783 in Reiss & Sohn’s sale 219 (23-24 April 2004), a 1768 edition with very similar title design. But these, it should be noted, were all printed on regular paper. ¶ We find precious few examples issued on board. The Library of Congress reports a 1694 ABC book printed on pasteboard. Gumuchian’s #160 sounds very much like ours: printed on board (carton), the first and last page in black and red, the final page with a woodcut of a teaching rooster. Theirs was printed in Halle by the widow of Christoph Salfeld, which could place it as early as 1703. Gumuchian’s #3 was similar, too, a Breslau imprint also on carton. Cotsen #4 is a ca. 1750 Pomeranian edition on "thick, unwatermarked gray paper, imposed in 8vo." The University of Michigan reports a 19th-century Kleiner Kinder grösste Freude"printed on board pages,” though this could just as well belong to the midcentury, when the machine-press age began producing more board books (and novelty children’s books of all kinds). ¶ At a glance, this does look like a run-of-the-mill case of printed waste used to make pasteboard for binding. That was our initial reaction, too. But the closer you look, the harder that is to maintain. Rather than sheets of printed waste later glued together—how we typically encounter print preserved in pasteboard—these appear to be the higher grade of pasteboard, produced by couching one sheet of freshly made paper directly atop the next: “pressure, not adhesive, caused the pulpy layers to cohere” (Miller). The fibrous bonds between our layers have left them far too difficult to separate, and that includes the printed surfaces and those beneath them. All to say, rather than our printed surfaces being simply glued to the layer beneath, the boards themselves must have been put under the press. ¶ Consider the odds, too. Judging by those few areas that have begun delaminating, there is no additional printed matter within, the versos of our printed layers also blank. The chance that we should just happen to find at the surface one side of each bifolium required for the complete text, each from an unperfected proof, and that each side should just happen to be properly backed up to produce a correctly collated codex, is vanishingly small. What's more, when backlit, [A]1 and [A]4 are clearly thinner at the fore-edge. This is consistent with the imposition of a sheet of common octavo, in which the fore-edges of those leaves would have been positioned next to the deckle—hardly definitive on its own, but supporting evidence that each bifolia came from the same sheet of pasteboard. ¶ Note, too, some scattered printing defects, especially on p. [12]. This is a relatively lumpy bifolium, with ink heavier and sloppier atop small lumps in lines 3 and 5. We find a similar phenomenon at the left end of the headline on p. [13], with smudged ink to the lower left of the lowercase 'o', and the portion of the rule directly beneath three times thicker than the rest. These sloppy areas again sit atop small lumps in the board. We would expect protrusions like these to pick up more ink. But the chance that those sloppy spots just happened to later find themselves aligned with lumps in a sheet of pasteboard is infinitesimal. ¶ This edition appears to be unrecorded, and any kind of hand-press board book is plainly rare. We must allow ample room for the vagaries of cataloging habits, and for differences in phrasing across various languages, but we find nothing like this in auction records and only the LC example among North American libraries.

PROVENANCE: According to our source, these bifolia were removed from the binding of a 17th-century German book.

CONDITION: Four loose bifolia printed on pasteboard, each very nearly a full millimeter thick. If so inclined, one could easily have a bookbinder or conservator fold these down the middle and stitch them through the spine for a finished pamphlet. We’ve lightly penciled page numbers in most lower margins to facilitate navigation. ¶ Soiled and worn, with adhesive and paper residue typical of waste pulled from bindings; scattered worming, affecting text; outermost bifolium with a little loss at the upper outer corners.

REFERENCES: Forum Antiquarian Booksellers, Children’s World of Learning 1480-1880 (1994), pt. 1, p. 1 (on the Haneboek: “an A B C book for the people, so they could learn to read the Bible in the vernacular, remained in popular use for over two centuries, never essentially changing its form or contents. It invariably consisted of one large sheet, folded into 16 unnumbered pages.”); Yann Sordet, Histoire du livre et de l’édition (2021),p. 340 (good summary of the printed abecedarian, noting they were typically single-sheet productions; “Largely distributed by colportage, they fit nicely into the production and distribution networks of popular print”); VIAF ID 103328846 (for Köhl's vitals); P. Deschamps, Dictionnaire de géographie ancienne et moderne a l’usage du libraire (Berlin, 1922), col. 1032 (for Plauen's first press); Gumuchian, Les livres de l’enfance (1979), v. 1, p. 12, #160; A Catalogue of the Cotsen Children's Library (2020), v. 1, p. 3, #1 (the dated 1703 edition), #4 (on thick paper); Julia Miller, Books Will Speak Plain (2010), p. 103 (on pasteboard, cited above); Philip Gaskell, A New Introduction to Bibliography (2012), fig. 50 (common octavo imposition); Andrea Immel, “Children’s Books,” The Book: A Global History (2013), p. 225 (on children’s books: “Like bindings, the text block is not purely utilitarian, but may be adapted to meet the audience’s special requirements or add a playful element. Durability, for instance, was crucial…those on heavy card stock are called board books”); Documentary History of Education in Upper Canada (1895), v. 3, p. 7 (for an 1828 proposal to print a spelling book and math book on pasteboard for a Canadian school); Alfred Ward, Book Production, Fiction, and the German Reading Public 1740-1800 (1974), p. 107 ("the German bookbinder had in fact always been more in touch with the ordinary reader and his tastes than had his colleague, the publisher-cum-dealer")

Item #748