Students' annotated Cicero

Students' annotated Cicero

In epistolas M. Tullii Ciceronis, quae familiares vocantur, Paulli Manutij commentarius; cum duplici rerum & verborum indice; cui additus est alter eiusdem ad M. Brutum & Quinctum fratrem

by Cicero | commentary by Paolo Manuzio (Paulus Manutius)

Frankfurt: Andreas Wechel, 1580

[8], 951, [1] p. | 8vo | *^4 a-z^8 A-2N^8 2O^4 | 162 x 102 mm

Title notwithstanding, this volume contains only Cicero’s Epistulae ad Familiares (with Manuzio’s commentary). The letters to Atticus and Quintus appeared in a subsequent volume, but one continuing our pagination. In 1580, Wechel produced a minor mess of issues of this work, with USTC hosting three records for various permutations. The frequency with which this particular volume has been cataloged as a standalone work suggests each volume might well have been available individually. WorldCat, for example, reports nine holdings across four records for standalone copies matching our pagination (246426791, 630750704, 16285429, 165391957). This would hardly have been unusual—the first volume would likely have been ready sooner anyway—and the publisher here admits to delays. In his letter to the reader, Wechel remarks that a lack of time (temporis angustia) prevented him from also including Cicero’s Epistulae ad Atticum, slated for a further volume still. ¶ Each of Cicero’s letters is here followed by Manuzio’s explanatio and argumentum. The explanatio, which could be quite long, expands on the grammar, classical references, and additional context. His argumentum, typically shorter, elucidates Cicero’s rhetoric, doubtless with the intention of helping his readers adapt Cicero’s rhetorical skills to their own correspondence. “Written rather than oral texts,” Anthony Grafton writes, “apparently personal and informal rather than public and theatrical, these offered the student a vast range of models of prose rather than the highly formal one of Cicero’s oratory. They also seemed more appropriate models for young men whose future tasks would involve far more document preparation than public speaking. Accordingly, students at early stages of their education, from Strasbourg to Rome, spent large amounts of time reading, translating, and imitating Cicero’s letters.” To be sure, Paul Grendler found Cicero’s Epistulae ad Familiares to be the single most frequently taught classical text in Venice during the 1587-1588 school year. And Wechel did intend this edition for students, as “a service to the young,” printed in small type “so that it would be portable and better suited to daily use” (title verso). He laments that the original Aldine edition could only be bought by wealthier individuals (a ditioribus emi posse) or found in distinguished libraries (splendidas in ferri bibliothecas). Wechel must be referring to the 1579 folio Aldine edition, the dedication from which he reprints here.

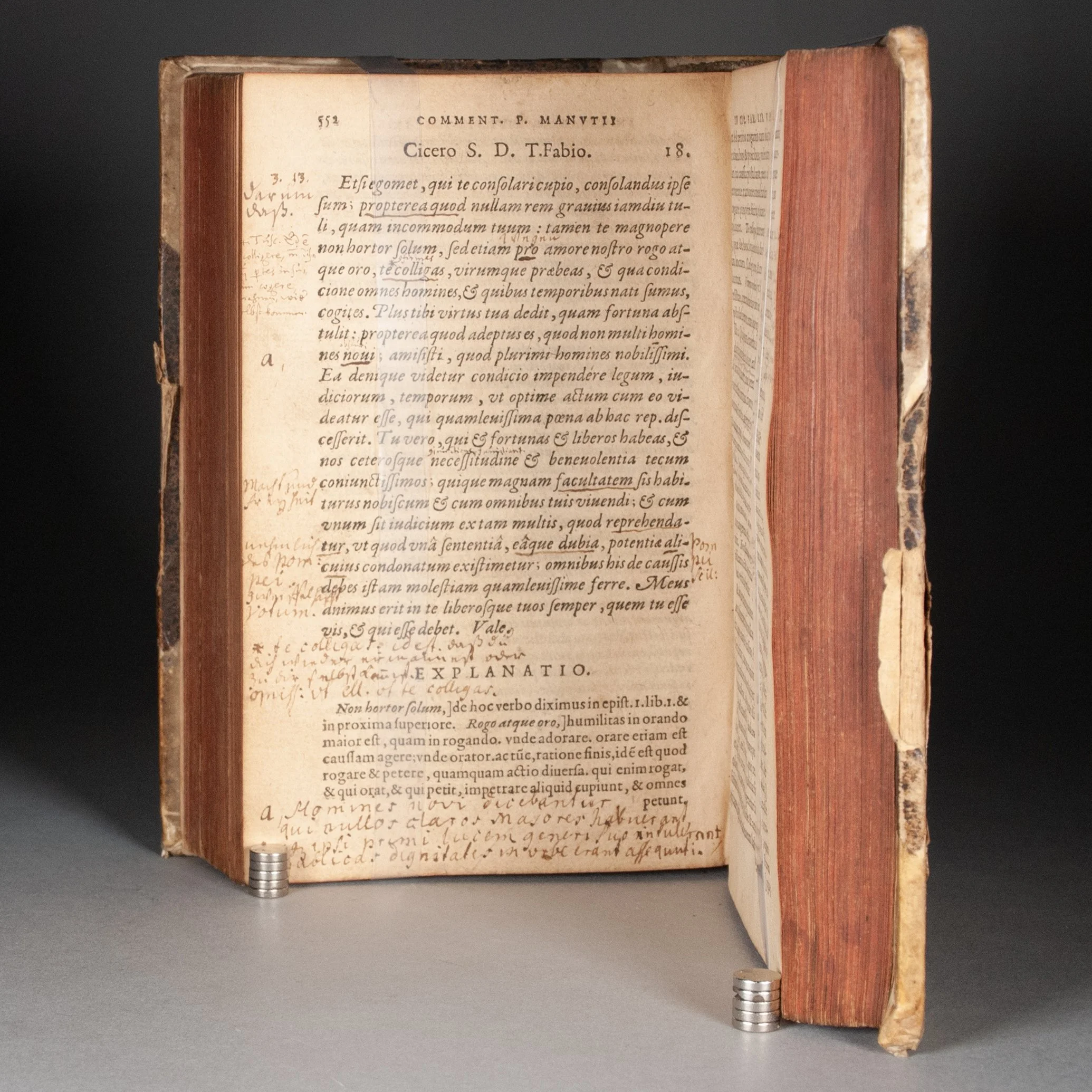

PROVENANCE: Annotated throughout by several early readers over the years, occasionally and not heavily, showing different levels of engagement. Many annotations are of the finding aid or nota bene variety, topical keywords simply pulled from the printed text and jotted down in the margin. There are occasional efforts at more sustained engagement. A longer note on p. 308 ends, Est alias bona epistola, ex qùam licet non [diffi…?] imitari (possibly something like, “It is another good letter, which may be imitated with little difficulty”). There are occasional interlinear annotations, which, as is often the case, betray a reader trying to make sense of the text. See especially p. 554-561 and 613-617, where, for example, a reader has scrawled the synonym deliberandum above Cicero’s considerandum (p. 561), one among many clarifying notes. Even the underlining is revealing, where we find readers noting just the kind of correspondence skills Cicero was meant to help develop. On p. 56, for example, an early reader has underlined part of Manuzio’s argumentum: “And a perfect recommendation generally consists of three parts: for with respect to he who is recommended, he is to be shown friendship, fairness in the matter, and our devotion.” When making one’s way in the world depended so much on others’ recommendations, skill in the matter would have been vital. ¶ A few early ownership signatures on the title, front fly-leaf, and final blank page of the Mosengeil family—one on the title, for example, of Arnold Johann Mosengeil, perhaps dated 1738. Ink stamp on the front fly-leaf of one Karl Schneider from Altenberg, near Wetzlar, a town north of Frankfurt.

CONDITION: Eighteenth-century half parchment and sprinkled boards; edges stained red. ¶ Title page detached (but present); scattered soiling; scattered mild dampstaining, mostly marginal; several millimeters shaved from the leaves, truncating the earliest marginalia (though the printed text still allows much of this to be inferred), but leaving intact the later marginalia; ink stain at top of first two leaves; small hole in the title, affecting only the first letter. Paper covering the boards torn and peeling; binding rubbed and soiled.

REFERENCES: VD16 C3020 (part of C3053); USTC 665636 (the two-volume set); H.M. Adams, Catalogue of Books Printed on the Continent of Europe 1501-1600 in Cambridge Libraries, C1933 ¶ Anthony Grafton, Bring out Your Dead: The Past as Revelation (Harvard, 2001), p. 109-110; Paul F. Grendler, Schooling in Renaissance Italy: Literacy and Learning, 1300-1600 (Johns Hopkins, 1989), p. 206; Frédéric Barbier, Gutenberg’s Europe (Polity, 2017), p. 19 (how important was letter writing: “we should remember that by the beginning of the fifteenth century the greatest Italian merchants wrote as many as 10,000 letters per year”)

Item #502