Annotator as industrious private scholar

Annotator as industrious private scholar

De gestis Romanorum libri quatuor, a mendis accuratissimè repurgati, unà cum adnotationibus Ioan. Camertis, quae commentarii vice in omnem Romanam historiam esse possunt; cui addita sunt & alia eiusdem argumenti, quae sequens recenset pagina

by Lucius Annaeus Florus | edited by Johannes Camers (Giovanni Ricuzzi)

Paris: Chrétien Wechel, 1542

[40], 326, [2] p. | 8vo | aa-bb^8 cc^4 A-V^8 X^4 | 173 x 103 mm

A nice little Paris edition of this frequently printed 2nd-century account of Roman history, largely drawn from Livy and first printed in 1471. Florus stands out as “the first African author whose prose work in Latin has survived” (Guédon). His book covers the founding of Rome through 9 CE and is commonly considered a condensed version of Livy—epitome often appears in the title—though facts were sometimes sacrificed at the altar of rhetorical effect. Today, if valued at all, it’s often for his potential use of Livy’s lost chapters. “However insignificant he is now, Florus was once a mainstay of the classical education…Throughout sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England and Europe, the Epitome was prized as an educational tool in its own right” (Jensen). In a classroom context, he might serve as a kind of introduction to Roman history (conveniently peppered with exemplary rhetoric) before students would move on to more advanced historians like Livy, Plutarch, and Tacitus. ¶ The 1518 Vienna edition is commonly cited as the first prepared by Johannes Camers, though at least some of his scholarship did accompany an edition in 1511. The Italian native was a professor in Vienna and prepared scholarly apparatus for a number of Latin works. Our printer, Chrétien Wechel, had a shop in the university quarter of Paris, and this edition could well have been meant to satisfy the academic market. He did quite a business both printing and publishing, “all on a considerable scale, comparable only to such enterprises as those of Estienne or Vascosan” (Armstrong). The present edition adds two other brief works at end: De Historia Romanorum Libellum by Festus (perhaps an epitome of his larger Roman history), plus a work on the lineage of Augustus, here attributed to Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus but really an anonymous medieval production. The book opens with an extensive index.

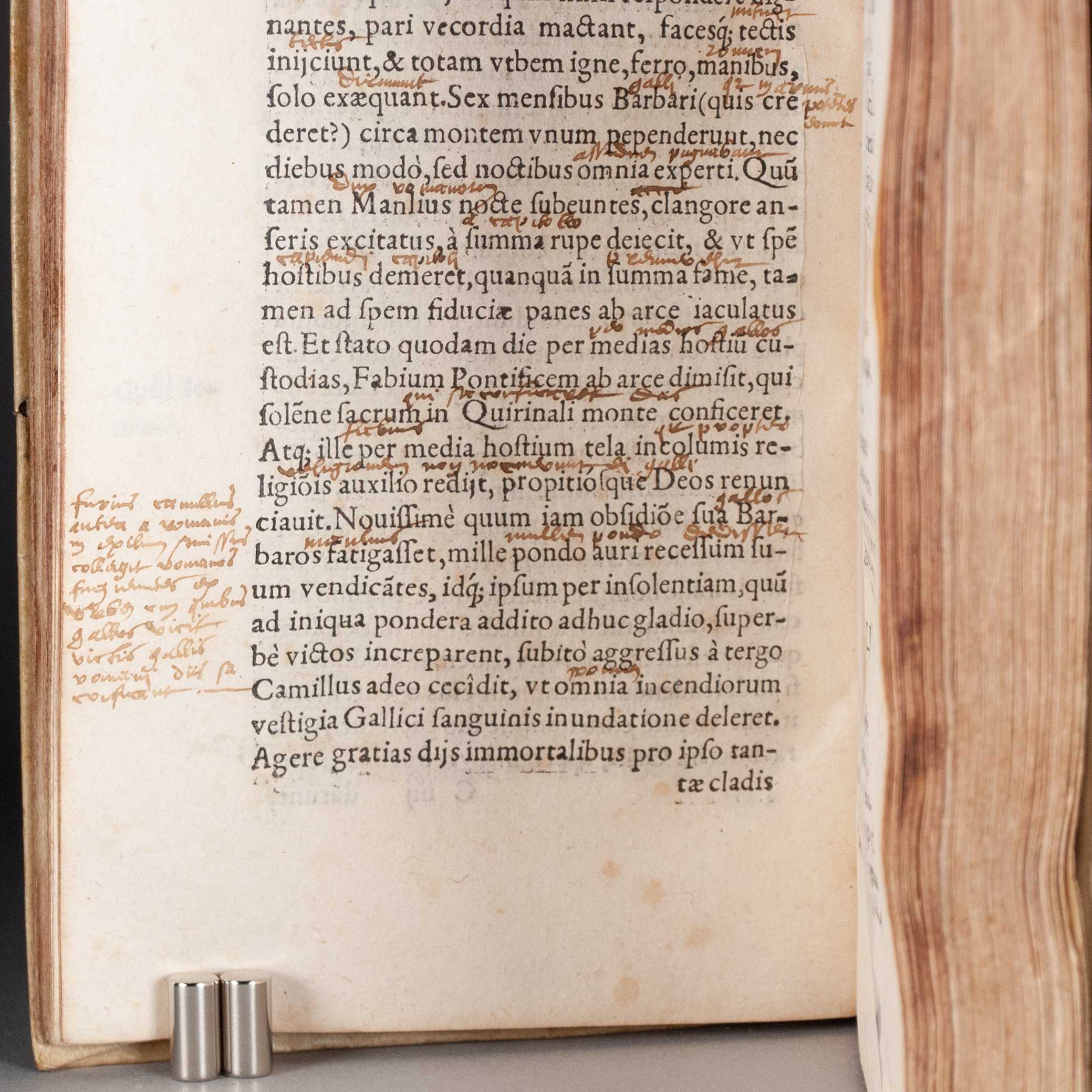

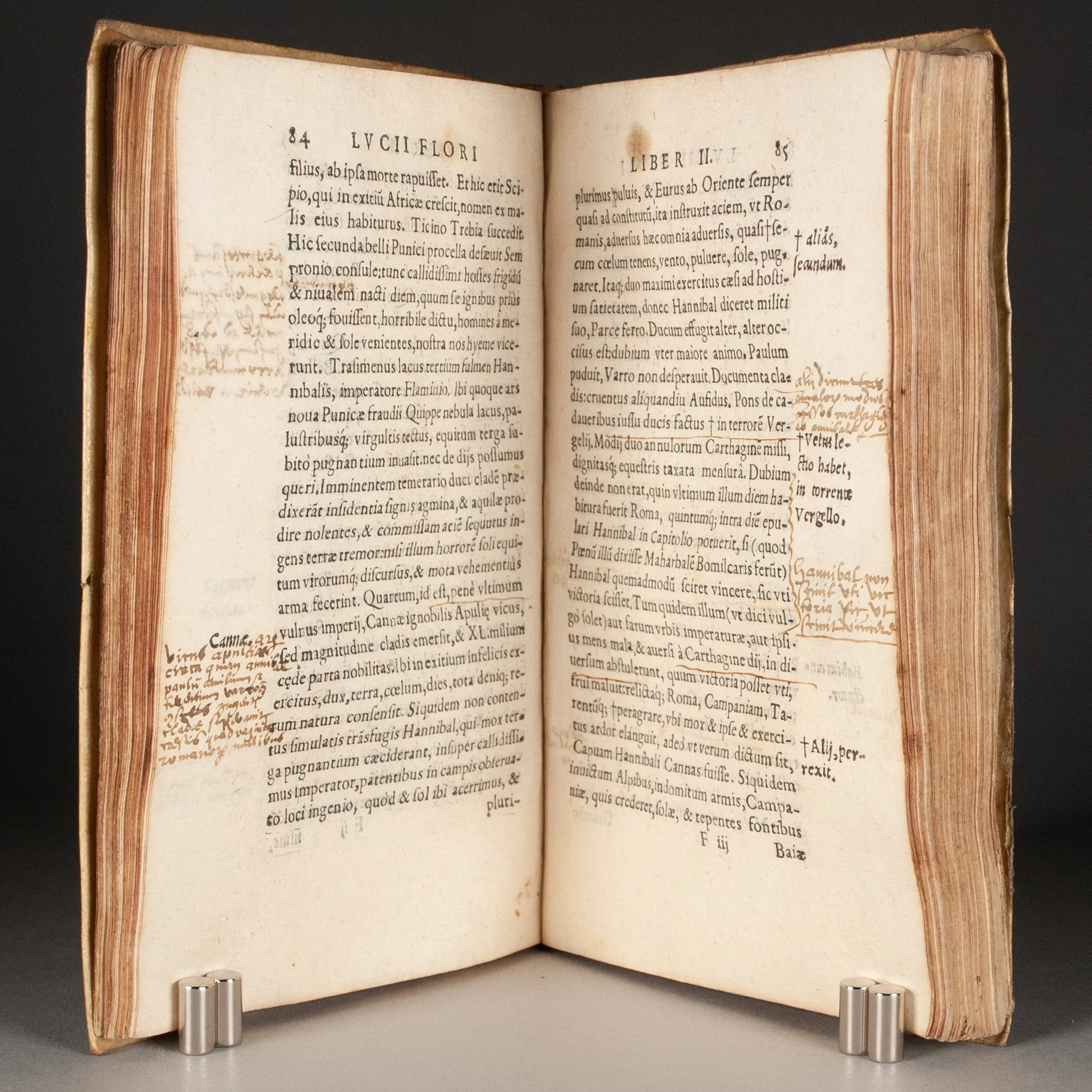

PROVENANCE: While some early annotated books bear the hallmarks of student use in a structured class setting, others present more as the work of independent study. Such is the case here, we believe—and private study guided, at least in part, by the editor’s citations for further reading, which we’re sure he would have appreciated. We have here two or three early readers at work, if not one working on multiple occasions. We count some 115 discrete marginalia, plus many interlinear glosses, concentrated in the first two books of Florus and the De Progenie Augusti at end. Most are several words long, a minority just a word or two, and many run to multiple lines in the margins. Most of these identify the reader’s desired takeaway from the printed text. Noted in the margin of p. 24, for example: “Romulus, first king of the Romans” (Romulus rex primus romanorum). Summary annotations like this abound. There’s another in the margin of p. 26 that rather intrigues us: “Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus, husband of Lucretia, first consul after the expulsion of the king” (Lucius Tarquinius collatinus maritus lucretiae primus consul post regis expulsionem). Here, while Florus’s text does mention the creation of consuls, he doesn’t actually name Collatinus as one of the first, much less his wife (though Lucretia is mentioned two pages later in Camers’s notes). It’s possible this book was used in a class setting, and that our annotator simply copied dictation from a teacher. Or that the information appears elsewhere in the book and was copied to this particular margin, where are reader thought it might be useful. Still, there’s evidence that our reader (or at least one of them) was consulting outside sources to augment their understanding of the subject. Camers made this easy, stuffing his notes with citations for other relevant sources. But our annotator has gone a step further and added page numbers for some of these sources in the margin. On 29, for example: Plutarchus in vita publicola pa 256. A note at the foot of p. 26 ends pag. 256. Just as Camers would have hoped, our reader has ventured outside the present text to digest the important nuggets of Roman history. Plutarch, cited frequently, appears to have been our annotator’s favorite source. He’s nearly exclusive; only on p. 314 did we find another source cited, pa. 128 of something, though we can’t make it out. We don’t mean to suggest any of this is somehow extraordinary. Such cross references were a common kind of marginalia, and obviously one encouraged by the additional printed apparatus. But we get particularly excited when page numbers are cited, lending annotations a more specific intertextual materiality otherwise absent. If one were so inclined, one might well be able to identify the particular edition of Plutarch our reader had at hand. ¶ This might today strike us as a great deal of trouble to pick up bits and pieces of ancient history. For a long time, however, an understanding of history was all but essential for those wishing to thrive in cultured society. Eighteenth-century Parisian elites, for example—peers and parlement officers alike—consumed history above any other genre, generously exceeding its share of book production writ large. “Even though the various groups of nobles did not read exactly the same sorts of history, history nevertheless provided them all with a base for their particular culture, rooting their aristocratic ambitions in the past and justifying them” (Chartier). And let’s not forget the politicians. “Political reading, in the Renaissance, meant above all the reading of history—the search, in classical and later texts, for examples of good and evil, prudent and imprudent conduct” (Grafton). Teaching students to find moral examples in classical literature was standard pedagogy anyway. In any case, it’s easy to forget that knowing history was once a requirement to serve the public, or simply to satisfy expectations of the landed and wealthy. You know, compared to those with all the power today. ¶ There’s plenty of underlining and still more evidence of reader engagement than these summary marginal comments, some of which Heather Jackson would call scholia, “a note that introduces information from outside the work that some scholar (usually) has judged relevant to it—a grammatical or textual point, an elucidation, a new illustration, a historical reference, an informing or contradicting authority.” There are briefer comments, simply keywords penned in the margin as a kind of a finding aid, what Jackson calls a rubric. There’s some interlinear glossing, too. We’re fond of p. 40 especially, where Barbaros is twice glossed as Gallos—which is to say, these particular Barbarians were French. “All these forms of interpretative labor mount up, so that a sufficient mass of individual glosses can become a free-standing glossary, a mass of rubrics an index, and a mass of scholia an independent commentary” (Jackson). ¶ Two ownership signatures on the title: one dated 1566 that we can’t make out (Leychirelle?), and a later one at top (Roullet de Valence?). Some faint scribbles on the covers.

CONDITION: Early limp parchment (probably manuscript waste, faintly visible through the parchment). ¶ Some light foxing, and a very faint dampstain in the lower margin (really only visible in the last couple gatherings, not near any text); a few large ink smears on p. 65. Parchment soiled and spine a trifle cocked; ties gone. A nice, solid copy.

REFERENCES: USTC 140383 ¶ Stéphanie Guédon, “Introduction: The Diversity of Written Sources from Roman Africa,” A Companion to North Africa in Antiquity (Wiley Blackwell, 2022), p. 234 (“His emphasis on virtus and fortuna greatly influenced the structure of his narrative, which takes certain liberties with regard to the historical reality provided by his sources” and the text “illustrates the schism that occurred, more generally speaking, between the rhetoric of the historian and the rhetoric of the orator in Latin sources as of Hadrian’s rule”); Freyja Cox Jensen, “Reading Florus in Early Modern England,” Renaissance Studies 23.5 (Nov 2009), p. 659 (“Florus inspired historical analysis, moralizing marginalia and comparisons with contemporary culture”), 660 (“Florus’ chief value today is usually perceived as being in the clues he gives as to what might be in the parts of Livy which have not survived, that is, everything covering the period from about 280 BC onwards”), 662 (time spent studying Florus “was intended as preparation for the more advanced fourth-year study of history [at Cambridge], which included Livy, Plutarch and Tacitus among others”), 663-664 (“The numerous editions of the Epitome of Florus throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries testify to the importance and popularity of the text…Moreover, the number of editions of the Epitome relative to other classical works increased dramatically from the late-sixteenth century onward”); Elizabeth Armstrong, “The Origins of Chrétien Wechel Re-examined,” Bibliothèque d’humanisme et renaissance 23.2 (1961), p. 343; H.J. Jackson, Marginalia (Yale, 2001), p. 45 (cited above), 87 (“Marking, copying out, inserting glosses, selecting heads, adding bits from other books, and writing one’s own observations are all traditional devices, on a rising scale of readerly activity, for remembering and assimilating text”); Roger Chartier (Lydia G. Cochrane, tr.), The Cultural Uses of Print in Early Modern France (Princeton, 1987), p. 194-195; Anthony Grafton, Commerce with the Classics: Ancient Books and Renaissance Readers (Univ of Mich, 1997), p. 203; Bernard M. Rosenthal, The Rosenthal Collection of Printed Books with Manuscript Annotations (Yale, 1997), p. 12 (“Distinguishing scripts can be a rather treacherous undertaking, because we know that the same person can use several writing styles and that, conversely, different persons can adopt a strikingly similar style suited to a certain topic or circumstance”)

Item #542