"Perhaps the greatest scandal...in French theater"

"Perhaps the greatest scandal...in French theater"

Sammelband of six French plays from the age of Molière

Paris, 1662-1683

6 plays in 1 volume | 12mo | 139 x 85 mm

A composite volume containing six rare comedies from the age of Molière:

Thomas Corneille. Le festin de pierre; comedie, mise en vers sur la prose de feu Mr de Moliere. Paris: Sign of St. Louis (Thomas Guillain and/or Jean Ribou?), 1683. [4], 115, [1] p. | pi^2 A-I^6 K^4. First edition.

Noël Le Breton de Hauteroche. Crispin musicien; comedie. Paris: Pierre Promé, 1674. [6], 136 p. | pi^4(-pi4?) A-L^8/4. First edition.

Le soldat Poltron; comedie. Paris: Jean Ribou, 1668. 48 p. | A-D^6. First edition.

Jean de Rotrou. Les sosies; comedie. Paris: Gabriel Quinet, 1668. [2], 92 p. | pi1 A-G^6 H^4. Possibly the second edition, after the first of 1638, but one of three editions (or issues) published in Paris the same year.

François Doneau. La cocue imaginaire; comedie. Paris: Jean Ribou, 1662. [12], 35, [1] p. | ã^6 A-C^6. Probably the third edition, after Ribou editions of 1660 and 1661; another edition of 1662, based on the present, has VIII, 26 p.

Charles Chevillet de Champmeslé. Les grisettes; comedie. Paris: Pierre Le Monnier, 1671. [4], 77, [1] p. | pi^2 A-F^8/4 G^4(-G4?). Second edition, but sometimes called the first, having been so reduced from its three-act first appearance that one might reasonably consider it a different work.

The headliner here is the first edition of Corneille’s Festin de Pierre, first performed in 1677. Corneille, younger brother of the much more famous Pierre, adapted his Festin de pierre from Molière’s Dom Juan. In truth, it’s a rather family-friendly version, stripped of its more risqué exchanges. Thus it stands as “perhaps the greatest scandal in the history of the French theater” (DeJean). Elements of Molière’s original production incensed the censors—which of course did nothing to quell popular demand. “In 1674, a year after Molière’s death, the long suppressed work was obviously still hot property.” But nobody could get their hands on a copy. (It didn’t appear in print until 1682, and even then heavily censored.) Thomas Corneille, however, managed to obtain a manuscript copy from Molière’s widow, “the one play whose publication had never been allowed.” Corneille struck the offensive bits and found great success with it. “Indeed, until the mid nineteenth century it continued to be staged instead of any text more closely linked to Molière’s, despite the fact that more authentic texts soon became available.” ¶ While the others may be more obscure, they surely have their own places in the history of French drama. Hauteroche’s Crispin was among a small group of plays that “prefigure the parodic procedures that inform Dancourt’s opera parodies,” a successful series of farces, and “alluded to the shift of power that had taken place in the Paris opera scene” (Powell). ¶ Le soldat Poltron still mystifies scholars. A note on our title page calls Claude de La Rose (aka Rosimond) the author, but this seems to have been debunked. “Fournel concludes that the play is so poor that the question of its authorship has no importance” (Lancaster). The play’s context is the 1667-1668 War of Devolution, when France invaded territories in the Northeast held by Spain. ¶ Les sosies, which takes as its subject the Greek legend of Amphitryon, is the oldest play in the group, first performed in 1636, and a theme Molière later explored in his own Amphitryon. Rotrou’s play was tapped for related stage productions in 1650 and 1653, refreshed with elaborate stagecraft and a new ballet context, respectively. “These precedents showed the vitality of the theme and also its adaptability, which offered Molière the further possibility of producing scenes relying heavily on clever machinery—the ‘pièce en machine’ had become quite popular, and Molière was always ready to utilize the latest techniques” (Forehand). ¶ Our Cocue imaginaire was Ribou’s shameless attempt to profit from the success of Molière’s Sganarelle, ou, Le cocu imaginaire. “This Cocuë imaginaire, which was never performed, was thus a new fraudulent calculation of Ribou. F. Doneau was content to render [démarquer] Sganarelle scene by scene, and often verse by verse, and even hemistich by hemistich” (Mongrédien). ¶ The final play in the volume, Champmeslé’s Les grisettes, is perhaps the least familiar in the group. “The principal merit of Champmeslé’s comedies,” according to 19th-century bookseller J. Techener, “consists above all in the faithful portrait of the little absurdities of bourgeois society.” The play did draw on some elements of Molière’s Dom Juan, so perhaps it’s fitting closure. ¶ All of these are scarce. We find a few North American copies of Corneille’s Festin de pierre, and this Crispin musicien at Harvard, but none for the other four plays. Of Les sosies, in fact, we find no copies at all.

PROVENANCE: An early owner has inked on each title what they seem to have thought was the date of the play’s first performance. Crispin with faint penciled markings throughout. Early list of contents handwritten on a front fly-leaf. Old description of the volume clipped from a bookseller’s catalog and tipped to a rear fly-leaf. Front paste-down bears the bookplate of Dr. Ernest Desnos (1852/1853-1925).

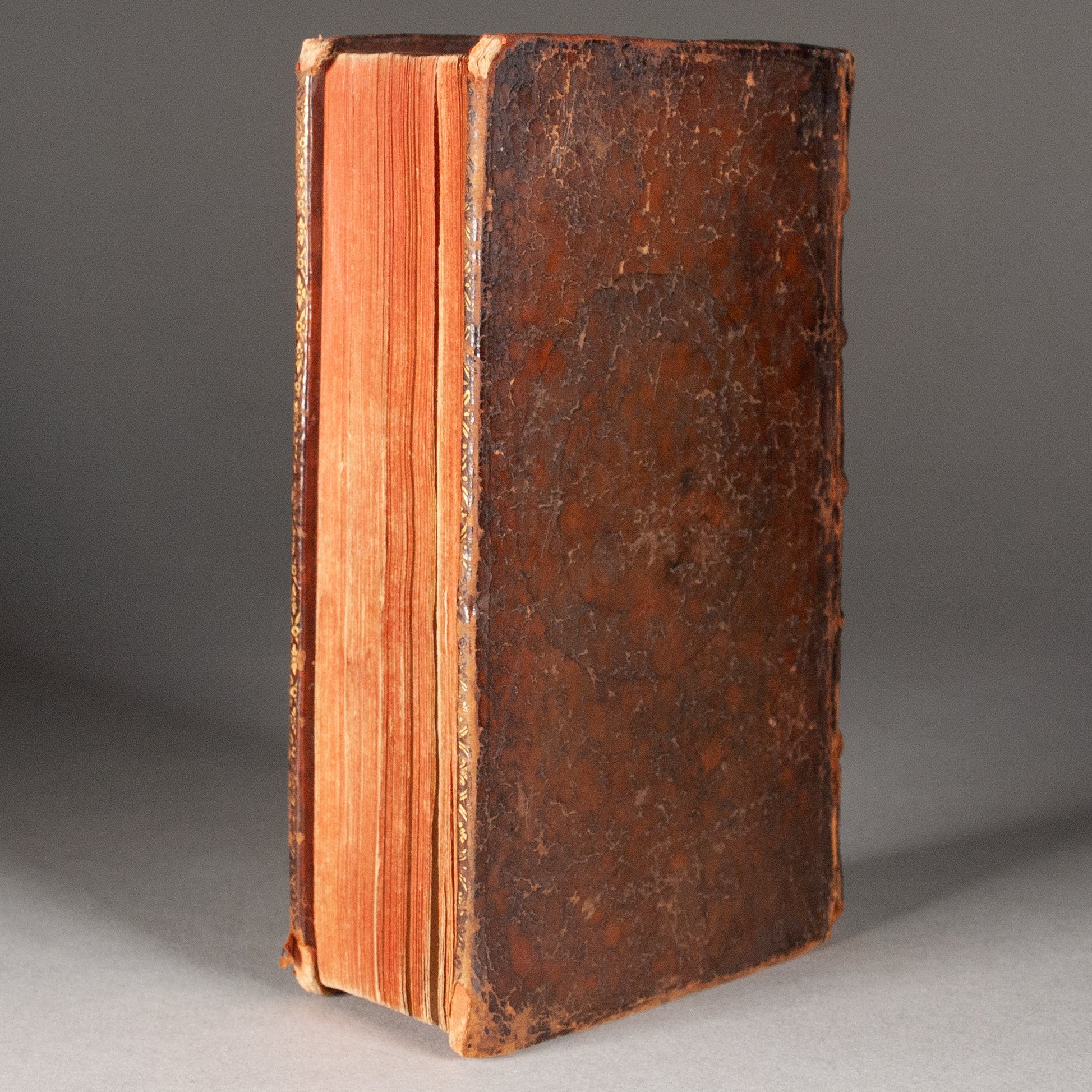

CONDITION: Early brown leather, the spine tooled in gold and with a leather label (Festin de Pierre); marbled endpapers; red edges. ¶ All plays cropped close, occasionally shaving a headline; E gathering of Pierre dampstained in the lower right, and maybe half a dozen leaves with large tears affecting text, A4 perhaps the worst, more than 3” long (partially repaired and with minor textual loss); Cocue dampstained and a bit ragged at the edges, the lower margin wormed, sometimes touching text; upper corner of Grisettes title torn away, affecting a single letter. Extremities worn, with the tailcap mostly chipped away, the headcap partially so; leather covering the joints split about an inch from the bottom, but all cords intact and the binding remains very strong; superficial surface crackling in the leather, perhaps just dry, perhaps a mottling solution gone wrong; once used as a coaster, with a ring on the rear board.

REFERENCES: Joan DeJean, “The Work of Forgetting: Commerce, Sexuality, Censorship, and Molière’s Le Festin de Pierre,” Critical Inquiry 29.1 (Autumn 2002), p. 59-65; Mouhy, Abrége de l’histoire du théatre François (1780), v. 1, p. 195 (Festin de Pierre, “performed on 12 February 1677, printed in 1683, in-12”); John S. Powell, “The Opera Parodies of Florent Carton Dancourt,” Cambridge Opera Jounral 13.2 (July 2001), p. 88-89 (on Crispin: “In this play, the master of the house is both a singer and harpsichordist, and his household servants display varying degrees of musical talent”); Henry Carrington Lancaster, A History of French Dramatic Literature in the Seventeenth Century: Part III the Period of Molière 1652-1672 (Johns Hopkins, 1936), v. 1, p. 334-335 (on Poltron: “The play is a farce, written with apparent haste for an audience that had recently witnessed preparations for the War of Dévolution, had seen officers providing their own equipment, soldiers who lacked the valor of which they boasted, and girls who were temporarily attracted by dreams of military prowess. The plot is slight.”); Walter E. Forehand, “Adaptation and Comic Intent: Plautus’ ‘Amphitruo’ and Molière’s ‘Amphitryon,’” Comparative Literature Studies 11.3 (Sept 1974), p. 205; W.L. Wiley, “Molière and Plautus: The Legend of Amphitryon,” Romance Notes, vol. 15, suppl. 1 (1973), p. 112 (“There are certainly some similarities between Rotrou’s Les Sosies (especially in its pièce à machine adaptation) and Molière’s Amphitryon, as Paul Mesnard has pointed out; but it is doubtful that Molière’s ‘first thought was of Rotrou, his second of Plautus,’ as H.C. Lancaster has suggested”); Georges Mongrédien, “’Le Cocu imaginaire’ et ‘La Cocuë imaginaire,’” Revue d’histoire littéraire de la France 72.5/6 (Sep/Dec 1972), p. 1028 (cited above, but the entire article offers a fascinating account of the dramatic fraud); Librairie J. Techener, Description bibliographique des livres choisis en tous genres (Paris, 1858), v. 2, p. 367, #10861; Lancaster, History of French Dramatic Literature, v. 1, p. 767 (“When Champmeslé brought out a second edition of his play, he reduced it to one act and changed the title”); M. Fuchs, Review of Joseph-Frédéric Privitera’s Charles Chevillet de Champmeslé, Revue d’histoire littéraire de la France 46.3/4 (1939), p. 247 (“Les Grisettes, M. Privitera tells us, was inspired by the Précieuses, with the addition of elements taken from Don Juan, from Bourgeois Gentilhomme, from Avare”)

Item #547