Plague prophylactic printed by an apothecary

Plague prophylactic printed by an apothecary

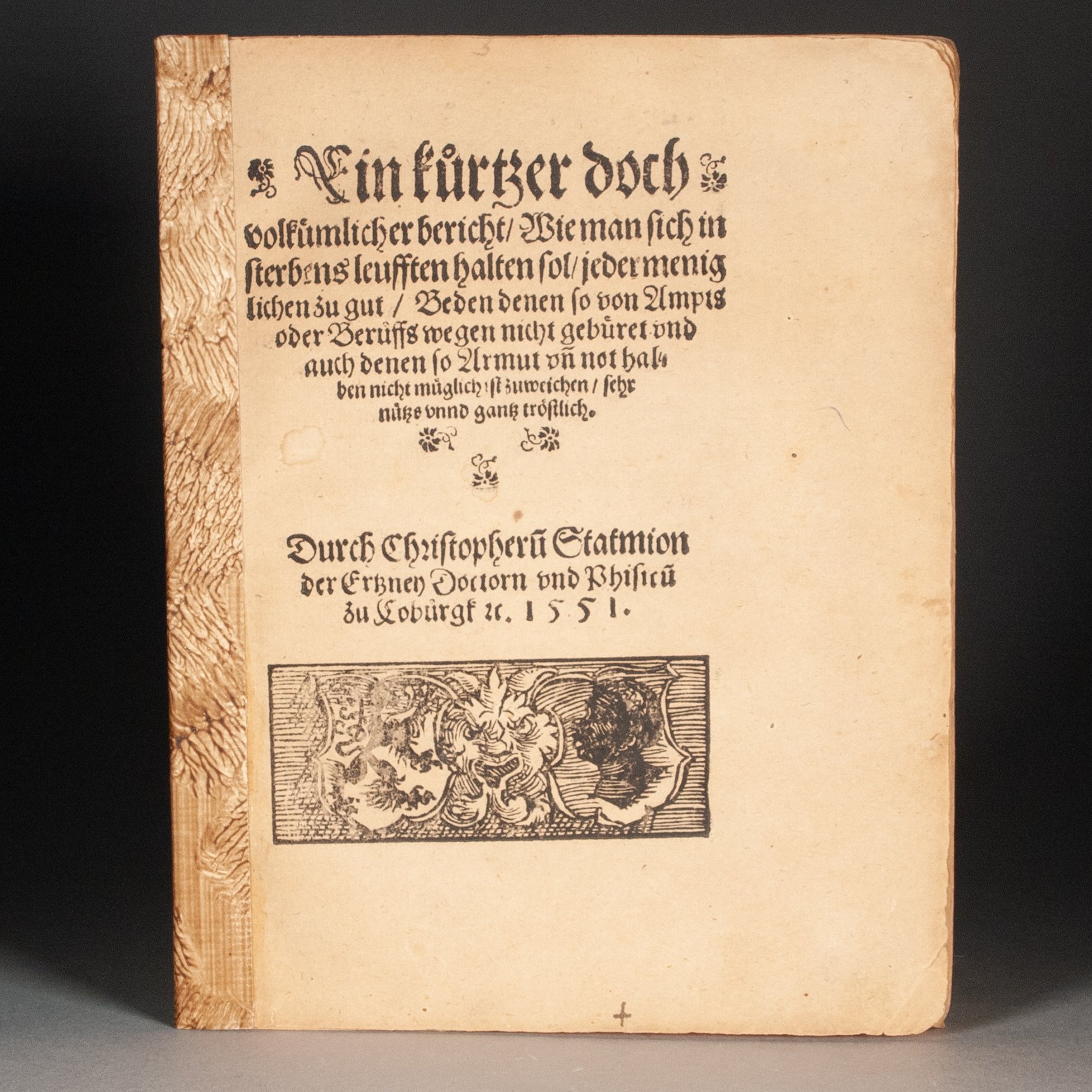

Ein kürtzer doch volkümlicher bericht, wie man sich in sterbens leufften halten sol, jedermeniglichen zu gut, Beden denen so von Ampts oder Berüffs wegen nicht gebüret und auch denen so Armut un[d] not halben nicht müglich ist zuweichen, sehr nützs unnd gantz tröstlich

by Christoph Mass (Christophorus Stathmion)

Coburg: Cyriacus Schnauss, 1551

[80] p. | 4to | A-K^4 | 189 x 148 mm

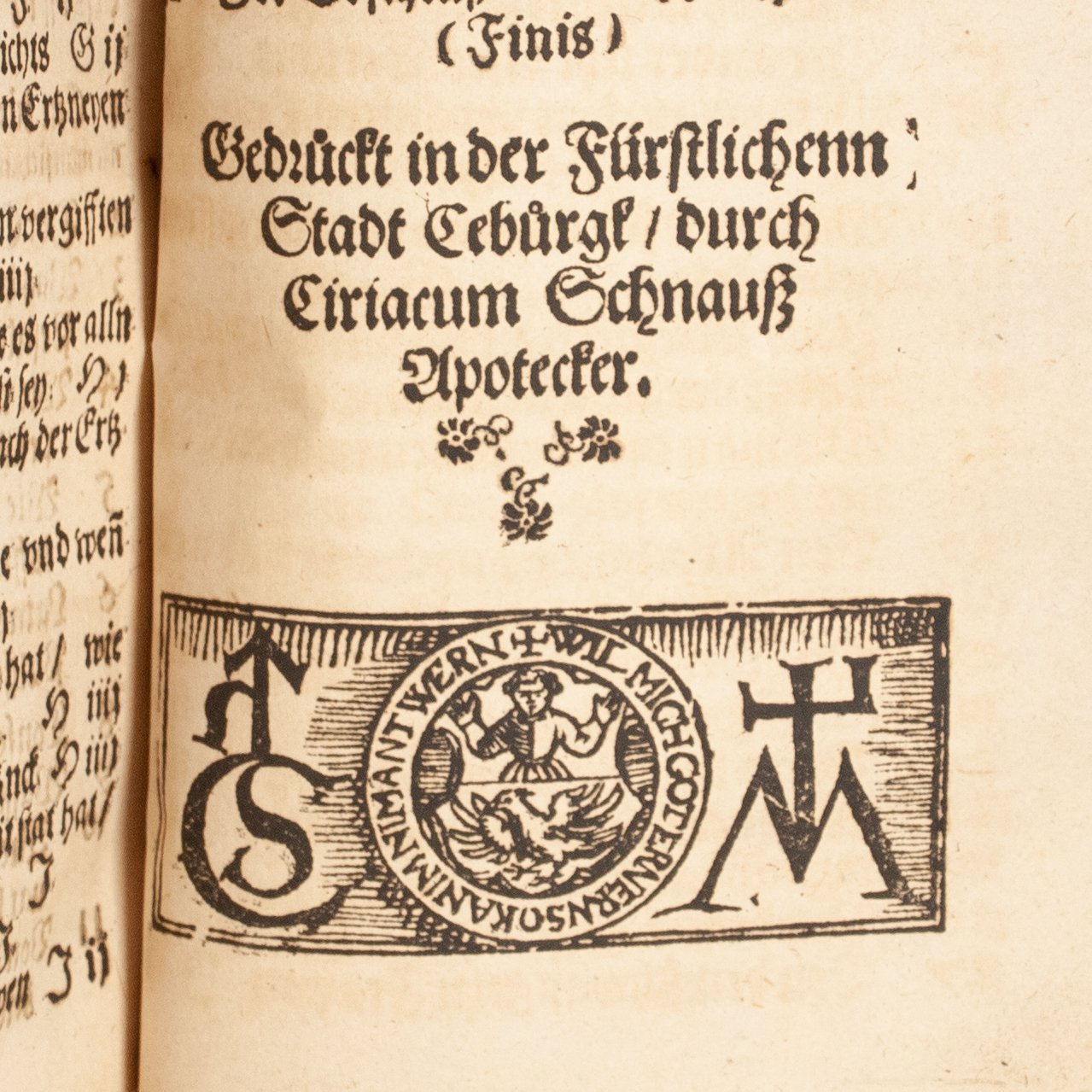

First and only edition of this guide to avoiding plague by Coburg's official city physician. Mass was by all accounts a respected man of science. Joachim Heller even gifted him a 1543 first-edition copy of Copernicus's De revolutionibus. He mostly trafficked in the astrologically informed, almanac-adjacent practica, annual prognostications that provided monthly advice for living your best, healthiest life. The present work is similar in spirit, if rather more startling. In his dedication, Mass warns of an "awful death or plague" (gemeinen Sterben oder Pestilentze) slated to beset the area, a prediction he notes can also be found in his latest prognostication. Of course, when facing imminent death, what could possibly be more useful than instructions for avoiding that death? Plague tracts like this were sometimes issued by local authorities, which might well have been the case here. Not only was Mass the town physician, but he dedicated the pamphlet to the city's officials and the title woodcut portrays the city arms. ¶ At a glance, the title rings of the Ars moriendi and similar late medieval guides to dying well, which focused on preparing your soul for death. But make no mistake, this is a medical guide. First things first, you must understand what causes the illness. "The first and most important cause of plague is the air that we breathe" (B1v). Mass covers astrological causes, too, and then explains how one can avoid plague-infected air. Several medicinal recipes follow, after which we find preventative measures to be taken in churches, schools, the town hall and other common spaces, followed by instructions to heads of households on protecting the air at home. If air is the primary external cause of plague, the author then comes to the primary internal cause: an excess of phlegm (Schleymen) in the body, especially in the lungs. And so follows advice on avoiding this. He goes on to discuss how to handle the infected, what to administer as remedies, how and when to let blood, specific instructions for pregnant women (Schwangern Frawen), how to handle people with boils, and other caretaking instructions. ¶ In the colophon, the printer identifies himself as an apothecary (Apotecker). While such a joint printer-apothecary role might seldom be made so explicit in a colophon, it wasn't an unusual trade combination. In Britain at least, “the sale of medicines was by far the commonest of ‘non-book-trade’ trades pursued by members of the book trade" (Isaac). Beneath the colophon is a woodcut with two devices: one, a CS monogram (our printer?); the other, an M surmounted by a cross (the author functioning also as publisher?). Whatever the case, this is early modern medical book synergy at its finest: The author predicts an imminent plague, writes a guide to protecting yourself from that plague, then has it printed by a local apothecary, from whom you can obtain the recommended medicines to survive said plague. We don't mean to suggest it was a scam. We fully expect both author and printer genuinely believed the plague was coming, and that both worked from an earnest sense of responsibility to a perhaps terrified community. “This pestilence, whether it was bubonic plague or whether it represented a confluence of afflictions conveniently gathered under the umbrella term of ‘plague,’ dominated European mortality and the European psyche from the fourteenth to the middle of the seventeenth century or longer. It gripped the imagination and sent shivers of fear down the spines of everyone when its presence was documented or when it approached" (Lindemann). ¶ We find a single copy in North America (National Library of Medicine), and our copy its only appearance at auction.

CONDITION: The signatures sewn together, with a simple spine covering of paste paper, but otherwise without covers. ¶ Title leaf a little darkened and a bit ragged at the extremities; small burn hole in fore-margin of D1; some creases and tears in the later rear fly-leaf.

REFERENCES: USTC 644532; VD16 S8645 ¶ Robin B. Barnes, "Astrology and the Confessions in the Empire, c. 1550-1620," Confessionalization in Europe, 1555-1700 (2017), unpaginated ebook ("Stathmion, a producer of hugely popular prognostications as well as more learned works, represented a Melancthonian conception of astrology that was just then achieving nearly doctrinal status among many Lutherans"); Owen Gingerich, An Annotated Census of Copernicus' De Revolutionibus (2022), p. 90, #I.82 (Mass's copy of Copernicus; "A note in the Leipzig matriculation book indicated that he [Mass] was 'a most learned doctor of medicine, physics and mathematics at Coburg in Franconia'"); Peter Isaac, "Pills and Print," Medicine, Mortality and the Book Trade (1998), p. 25 (cited above), 41 (“Before the days of ‘proper’ professional training for pharmacists, it seems to have been universal that members of the book trade also dealt in nostrums—clearly without requiring to demonstrate any understanding of the therapy involved"); Mary Lindemann, Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe (2010), p. 62 (“After the invention of printing in the mid fifteenth century, municipalities and territorial states began issuing short pamphlets dealing with ‘preservation and cure.’ These so-called plague tracts advised on rules of diet and regimen and proposed treatments, such as lancing buboes and then cauterizing wounds. A virtual flood of such advice, often in the form of self-help literature, poured off the presses in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries."), 64 (cited above)

Item #817