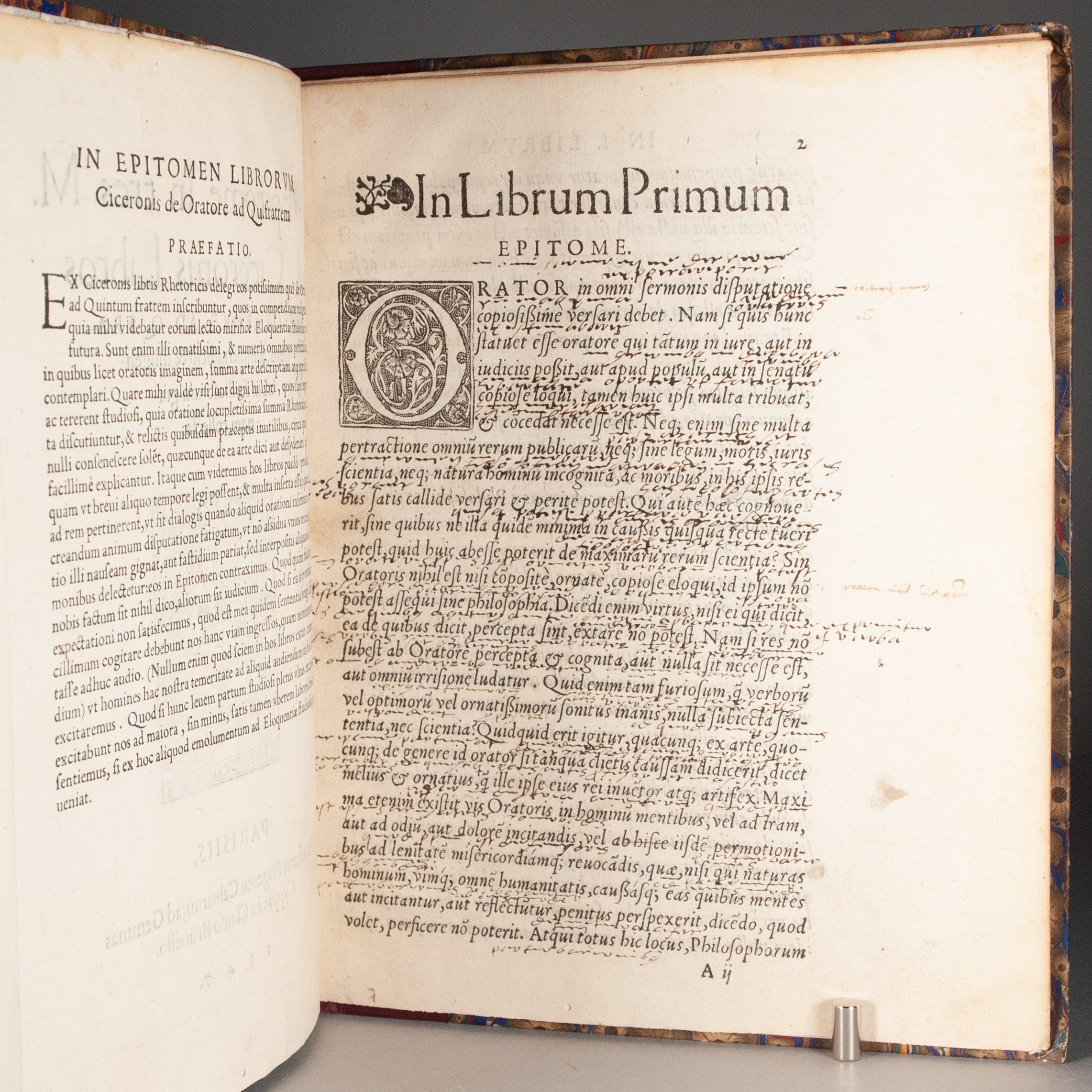

Annotated Cliff's Notes

Annotated Cliff's Notes

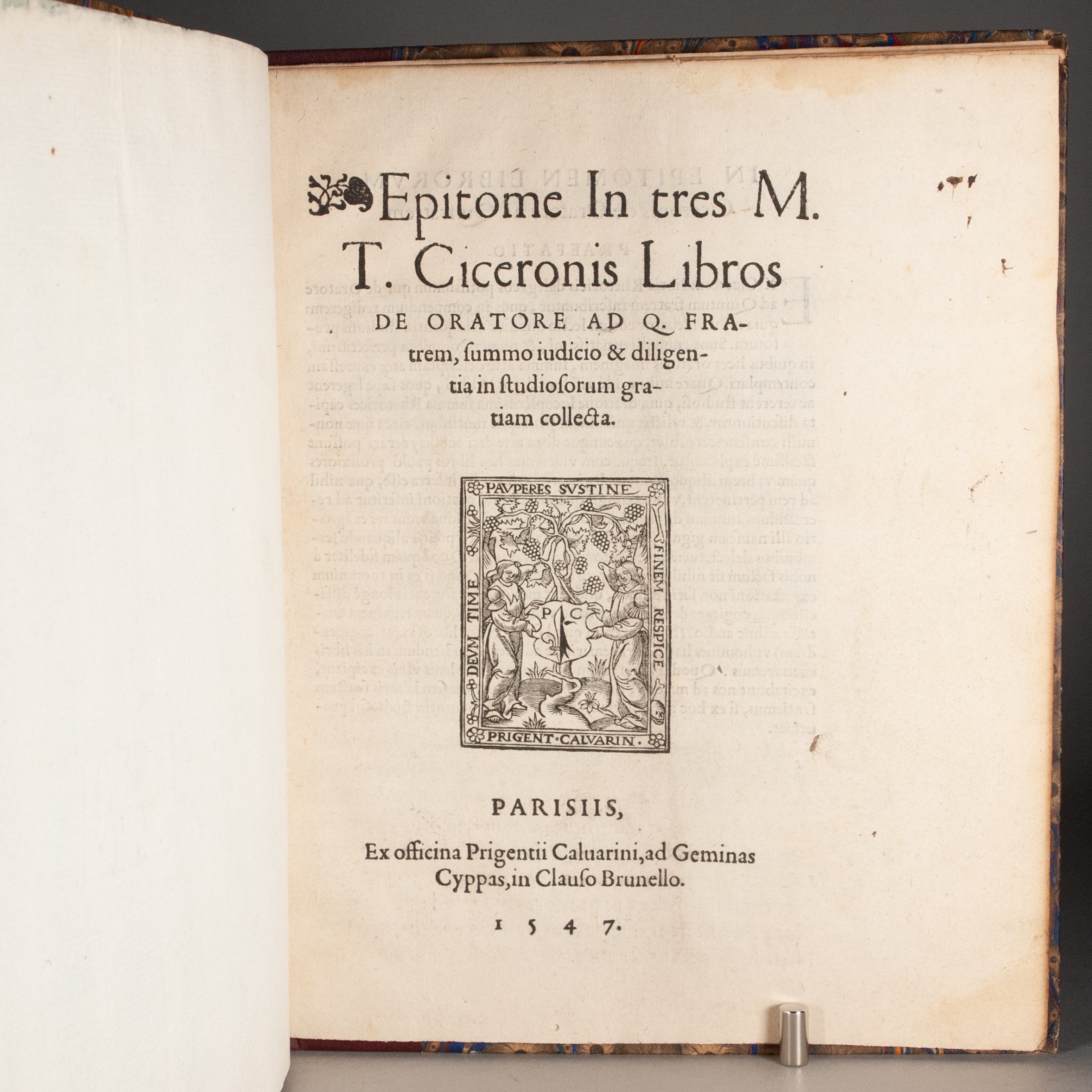

Epitome in tres M.T. Ciceronis libros de oratore ad Q. Fratrem, summo judicio & diligentia in studiosorum gratiam collecta

by Cicero

Paris: Prigent Calvarin, 1547

12 leaves | 4to | A-C^4 | 216 x 170 mm

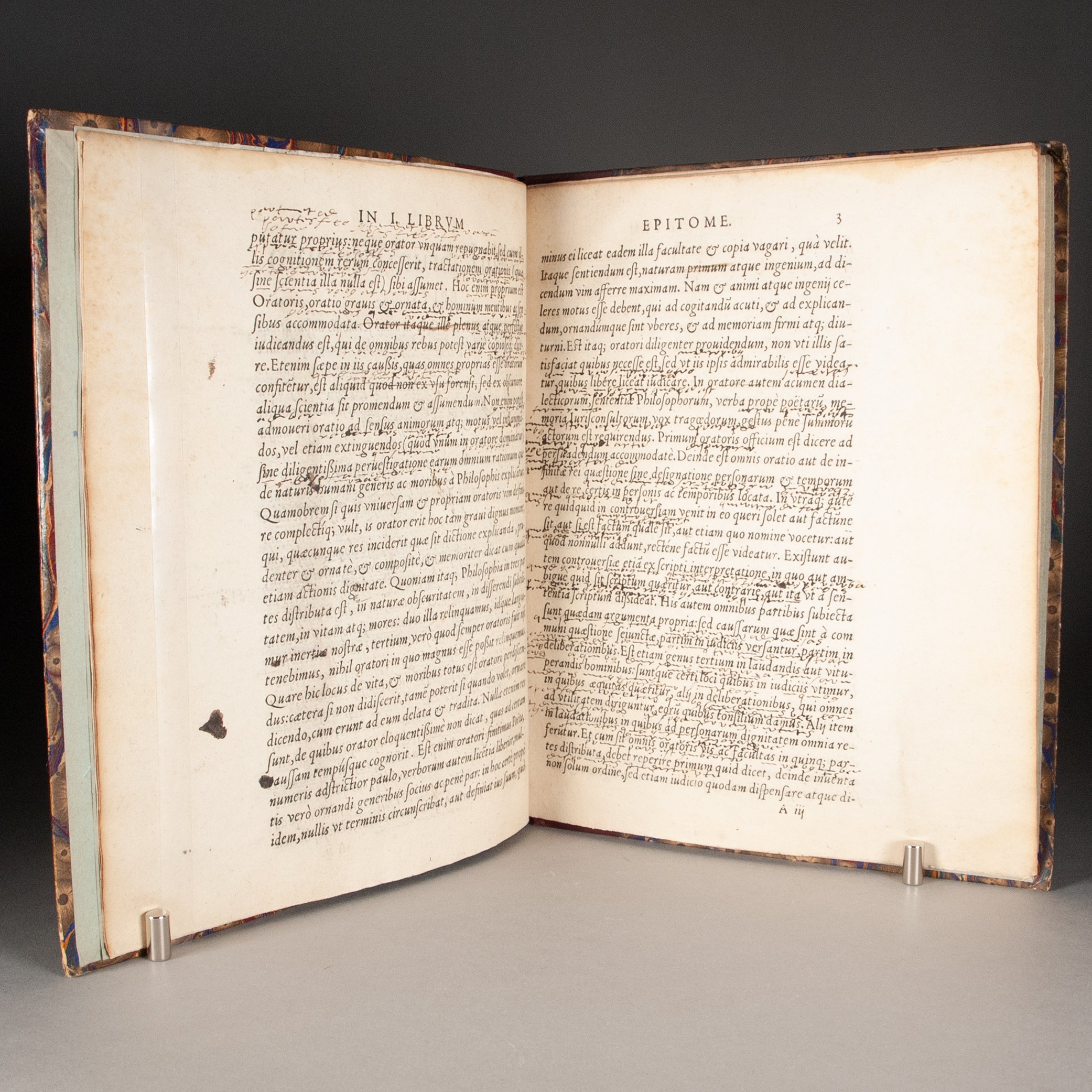

A rare, early epitome of Cicero's De Oratore intended for the Paris student market, its preface hoping the compact text will benefit students of eloquence (eloquentiae studiosis profutura). We find Calvarin editions of 1546 and 1549, and two editions of 1543 (one unattributed, one printed by Michel de La Guierche). Calvarin seems to have been especially drawn to the publication of epitomes, as we also find from his press a 1537 epitome of Erasmus's De copia verborum; a 1537 epitome of Cato; a 1541 epitome of Boethius on arithmetic; a 1542 epitome of Rudolphus Agricola's De inventione dialectica; and a 1548 epitome of Aristotle on discourse. This quarto format was quite popular among academic publishers in Paris at the time. Similarly sized pieces were frequently bound together and often show signs of extensive engagement by students. ¶ While epitomes and abridgements have their own ancient roots, the printing press is sometimes blamed for the proliferation of these shortcuts to learning. Such books were relatively uncommon in the earliest days of print. The first thirty-odd years of the European press were largely characterized by unaccompanied original texts. Even commentaries didn't take off until the mid 1480s. But FINDING ONE'S WAY IN AN ENDLESSLY EXPANDING TEXTUAL LANDSCAPE became increasingly difficult as the decades wore on. Of course, larger books were more expensive, too, which must have rendered alternatives like this 24-page epitome more attractive still. What's more, the genre had an established role in the classroom. Writing one's own epitomes was considered a useful pedagogical method, for students to "produce their own summaries as a way to secure their understanding of a subject and to exercise their rhetorical flexibility," though "there is also evidence that teachers provided their students with readymade epitomes" (Chloe). ¶ If anyone warranted a shortcut to content, surely it was Cicero. Whether in speech or letter writing, he was the model to emulate. Then as now, rhetoric and oratory, the capacity to move others to action, were vital to gaining and maintaining power and influence. There must have been a real demand for a fast path to the master orator's advice. Certainly our compiler thought so— perhaps Calvarin himself?—who "saw that these books were a little longer than they could be read in a short time, and that many things were inserted which had nothing to do with the matter" (videremus hos libros...quae nihil ad rem pertinerent). It's a telling justification, one that SPEAKS TO STUDENTS' ENDURING DESIRE TO ACQUIRE KNOWLEDGE FASTER AND WITH LESS EFFORT. ¶ While epitomes and their ilk clearly became popular, they were not universally embraced. "Indeed, early print genres such as the abridgment, epitome or printed commonplace book, whose purpose was to facilitate a reader's access to information, were in general a site of intense concern for those who felt they compromised the integrity of knowledge or professional practice" (Cormack and Mazzio). Socrates worried that reliance on the written word would erode one's memory. And the National Council of Teachers of English recently suggested decentering the book in school curricula. The more things change, right? ¶ We locate no other copies of this edition, but it's been indexed by Google Books, so it likely exists somewhere else.

PROVENANCE: Here with roughly three pages of early interlinear annotations, demonstrating considerable engagement with the first of Cicero's three books on oratory. It's a cramped hand, but from what we can make out, our reader appears to engage with content rather than grammar and syntax, perhaps transcribing comments provided by a teacher, as was then common practice. Our reader might have had a perfectly good reason for annotating only the first few pages, but we still find a kind of CHARMING, TIMELESS QUALITY TO THE INCOMPLETE EFFORT—the appearance that a student couldn't even work through 24 pages of what are basically Cliff's Notes. Once again, the more things change, right? ¶ Twentieth-century bookplate of Henri Barthélemy on front paste-down, illustrating a compositor in front of his type case.

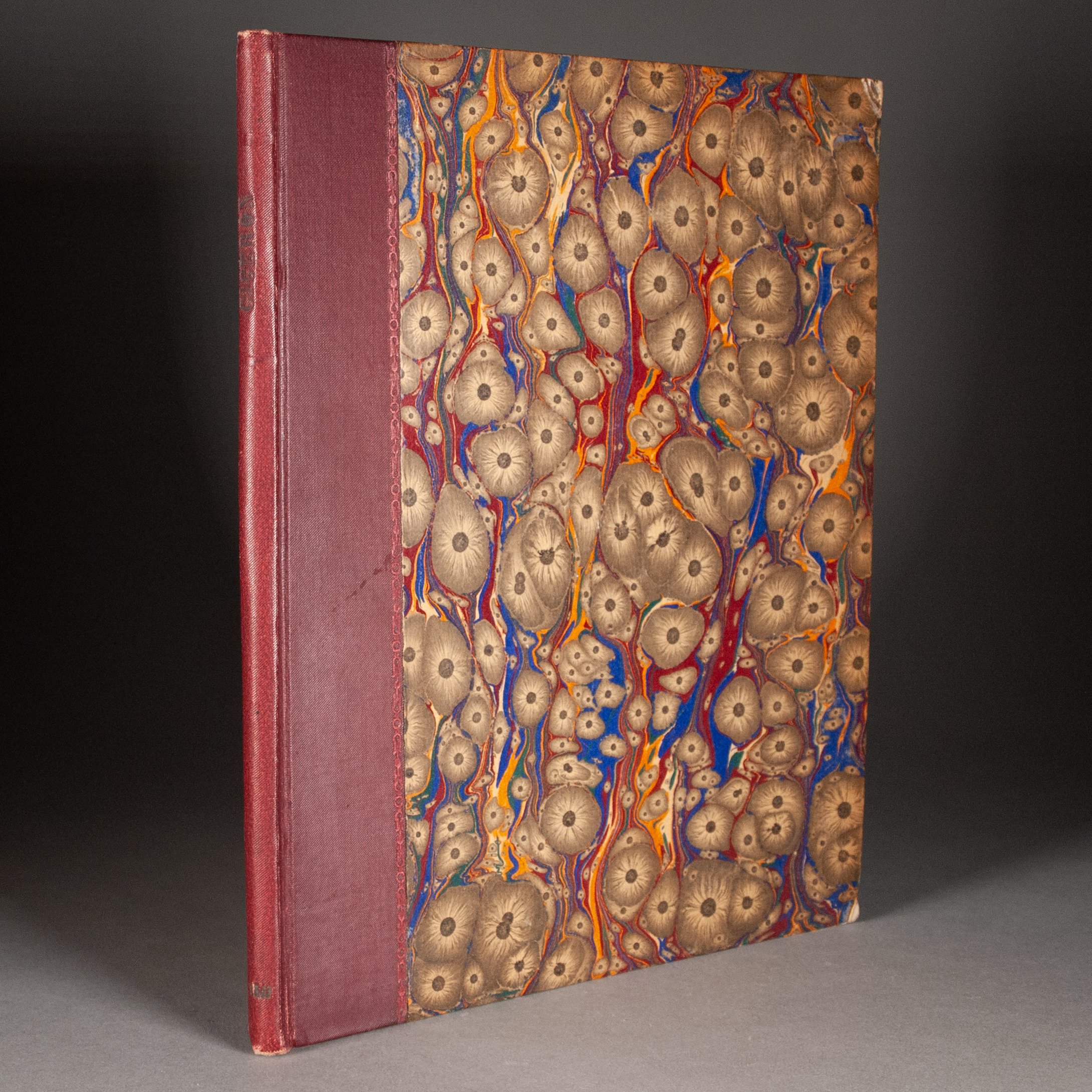

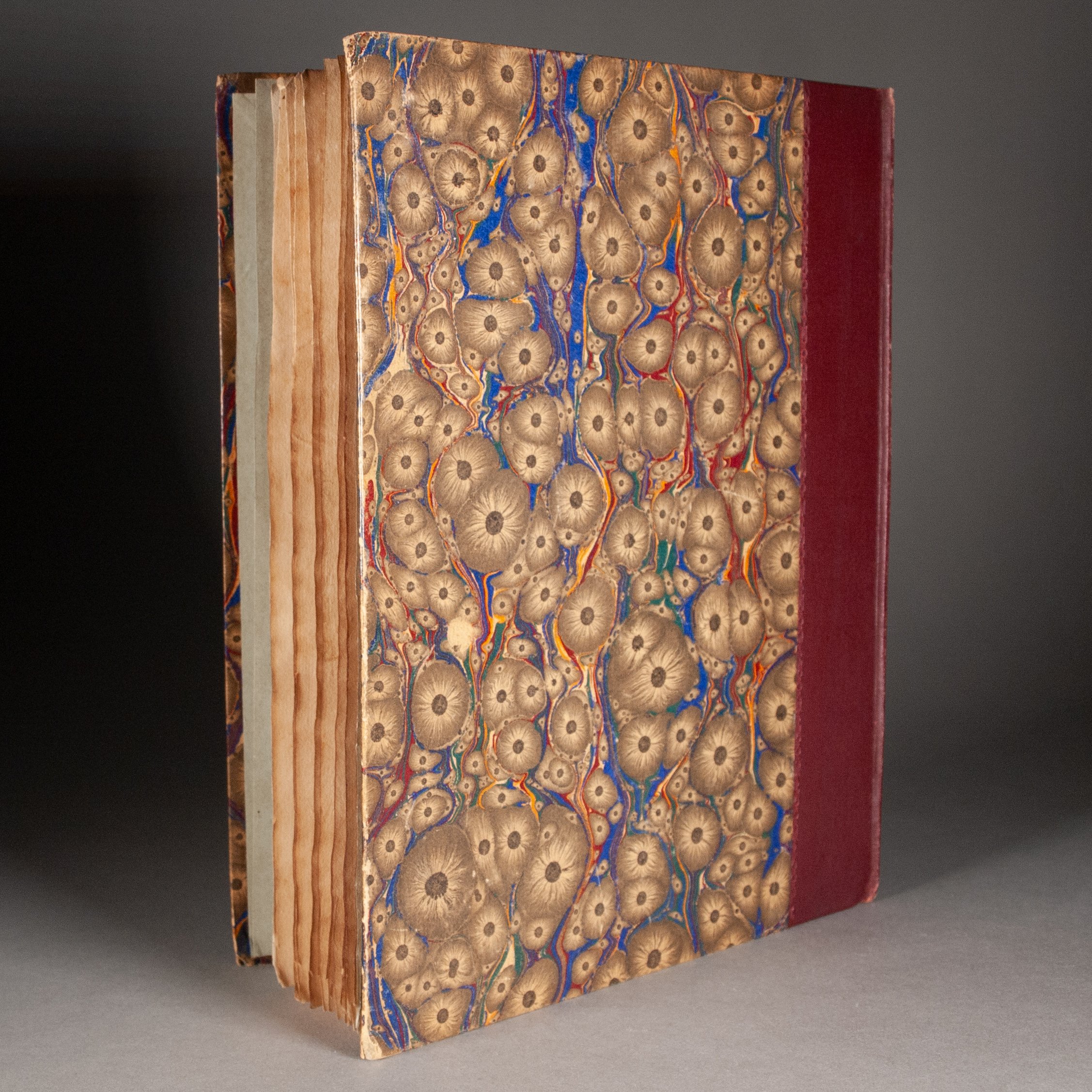

CONDITION: Twentieth-century quarter maroon cloth and marbled boards. ¶ First few leaves a bit soiled, including some ink stains; single small wormhole through the lower margin, nowhere near the text.

REFERENCES: Bradin Cormack and Carla Mazzio, Book Use, Book Theory: 1500-1700 (2005), p. 12 (cited above), 13 ("Epitomes and abridgments came into being as a response to the phenomenon of print itself. Emphasizing the destabilizing effects of the early modern press, Ann Blair has cataloged how authors, printers and readers responded to a disorienting 'information overload' and unwieldy 'over-abundance of books' by producing reference works like dictionaries and concordances and by refining navigational tools within the book such as the index, preface or table of contents."), 44 (a similar annotated quarto for Paris students: "the manuscript annotations (ca. 1560) that fill this book and its margins are probably a student's notes on his professor's lecture"); Wheatley Chloe, "Abridging the Antiquitee of Faery Lond: New Paths through Old Matter in The Faerie Queene," Renaissance Quarterly 58.3 (Fall 2005), p. 861 (cited above; "A more general reading public was also increasingly targeted as a viable market for predigested texts"); Michael Ullyot, The Rhetoric of Exemplarity in Early Modern England (2022), p. 119 ("The necessity of abridgements is evidenced by their ubiquity...These texts provided readers not only with compact summaries of complex subjects and long narratives but also with guidance...on how to interpret those subjects or imitate their models. In this, they could point to ancient traditions of rhetoricians offering their abridgements or miscellanies to economize reading and guide interpretations."); Paul F. Grendler, Schooling in Renaissance Italy (1989), p. 124 (“Cicero’s prose, especially the letters and orations, became canonical in Italian Renaissance Latin schools. Students learned to write like Cicero, and Ciceronian style became the standard.”); Joseph M. Levine, "'Et Tu Brute?' History and Forgery in 18th-century England," Fakes and Frauds: Varieties of Deception in Print and Manuscript (1989), p. 74/76 (“Cicero appealed to everyone in the 18th century as the greatest orator and prose writer of antiquity, a statesman and philosopher who had played a signal role in some of the most notable and best reported events in ancient history. His rhetoric was taught in the schools; his orations and letters were used as models of prose style; his philosophical works were regarded as an encyclopedia of wisdom in all worldly matters; and he could be read by an English in English, French, or the original Latin.”); Ann Blair, “The Rise of Note-Taking in Early Modern Europe,” Intellectual History Review 20.3 (2010; accessed via Harvard’s DASH repository), p. 23-24 (“Note-taking was taught in the wake of humanism in two principal ways. On the one hand adolescents studied the Latin classics (such as Ovid, Vergil and Cicero) under the direction of a master who commented on the text, explaining its grammar, figures of speech and cultural references. This teaching generated printed schooltexts which pupils annotated heavily in the margins, between the printed lines and often on blank pages added for the purpose."); Ann M. Blair, Too Much to Know (2010), p. 248 (on books annotated only at the beginning, "a pattern typical of books that were read sequentially"); H.J. Jackson, Marginalia (2001), p. 100 (“For the collector who acquires an annotated book and for the scholar who wants to use the evidence of marginalia, it seems to me that there is a net gain in abandoning the notion that marginalia are innocent and transparent: if we have to let go a pleasing illusion, we end up with more human drama and come closer to the truth besides. Marginalia are the product of an interaction between text and reader carried on—since books are durable objects—in the presence of silent witnesses.”), 256 ("Marginalia for all their faults stay about as close to the running mental discourse that accompanies reading as it is possible to be, and if we want to understand that process we are better off with them than without them")

Item #667