Annotated, hand-colored, pricked and pounced

Annotated, hand-colored, pricked and pounced

Le blason des armoiries, auquel est monstree la maniere de laquelle les anciens et modernes ont usé en icelles; traicté, contenant plusieurs escus differens, par le moyen desquels on peut discerner les autres, & dresser ou blasonner les armoiries; reveu, corrigé, amplifié par l'auteur avec augmentation de plusieurs armoiries, tant anciennes que modernes

by Jérôme de Bara | with contributions from François Béroalde de Verville and Pierre Manson

Lyon: Jean de Gabiano and Samuel Girard, 1604

Large fragment, 206 of 260 pages: p. 35-181, 183-201, 206-207, 210-247 | 8vo | E^4(-E1) F-2B^4 2C^4(-2C1,2,4) 2D-2G^4 2H^4(-2H4) | 232 x 143 mm

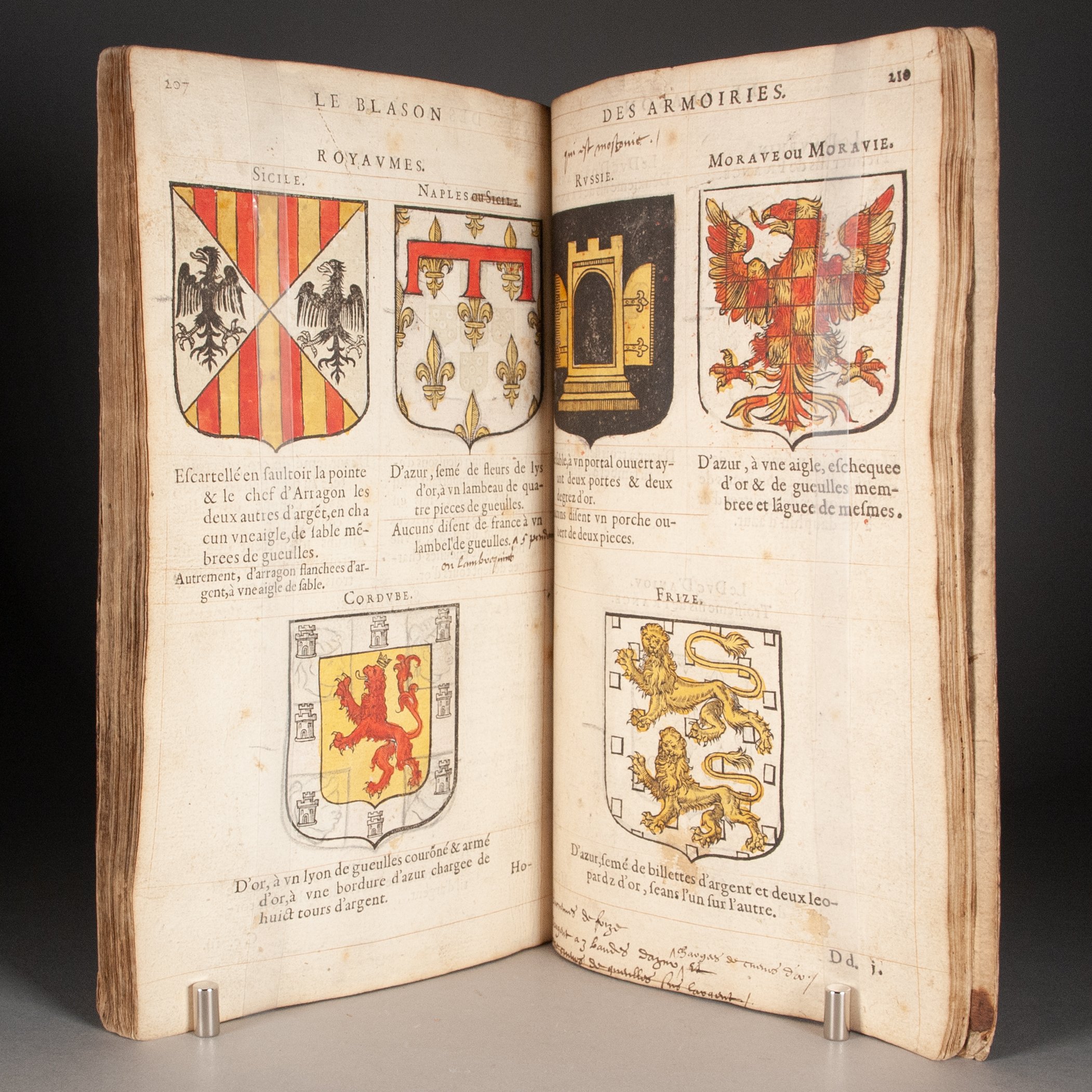

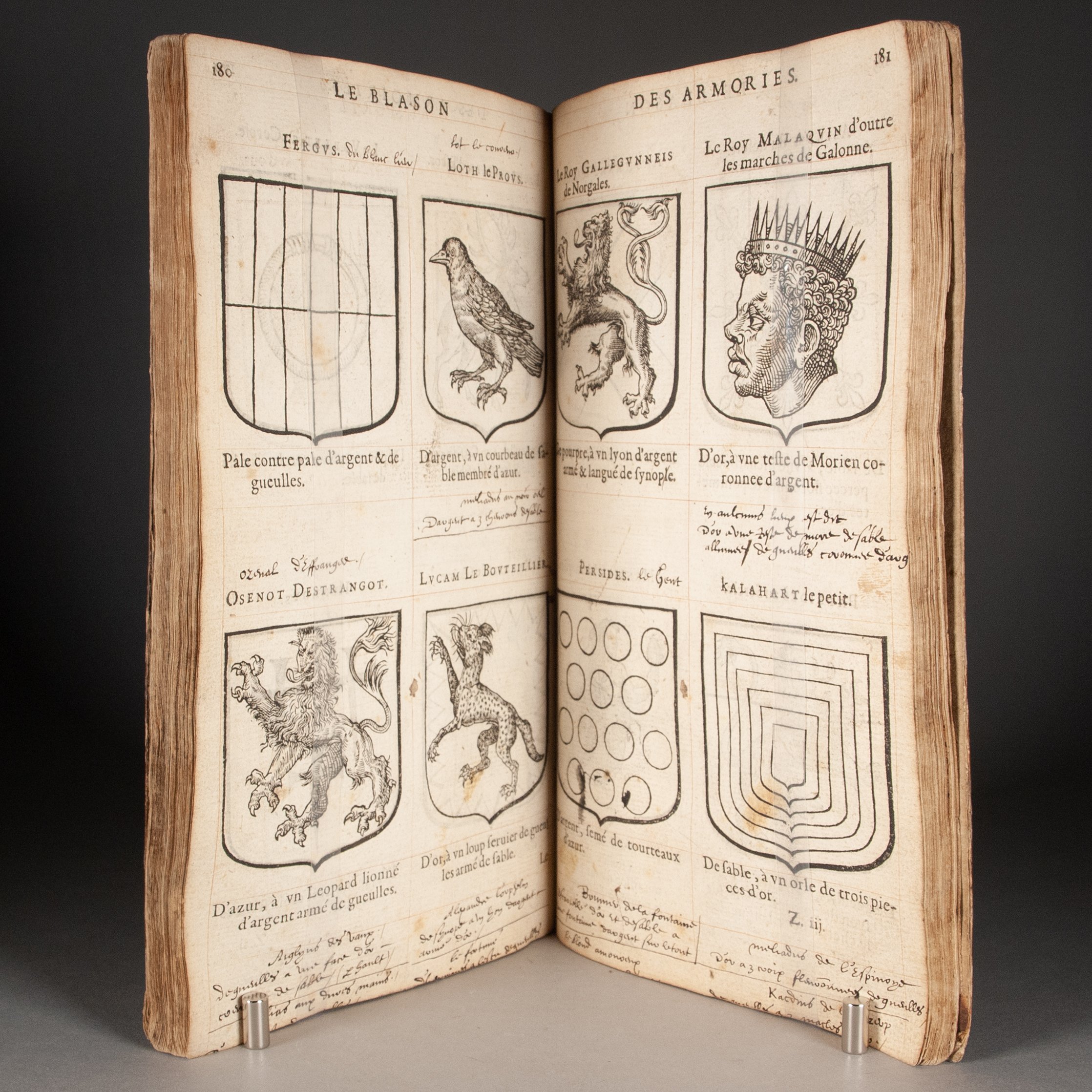

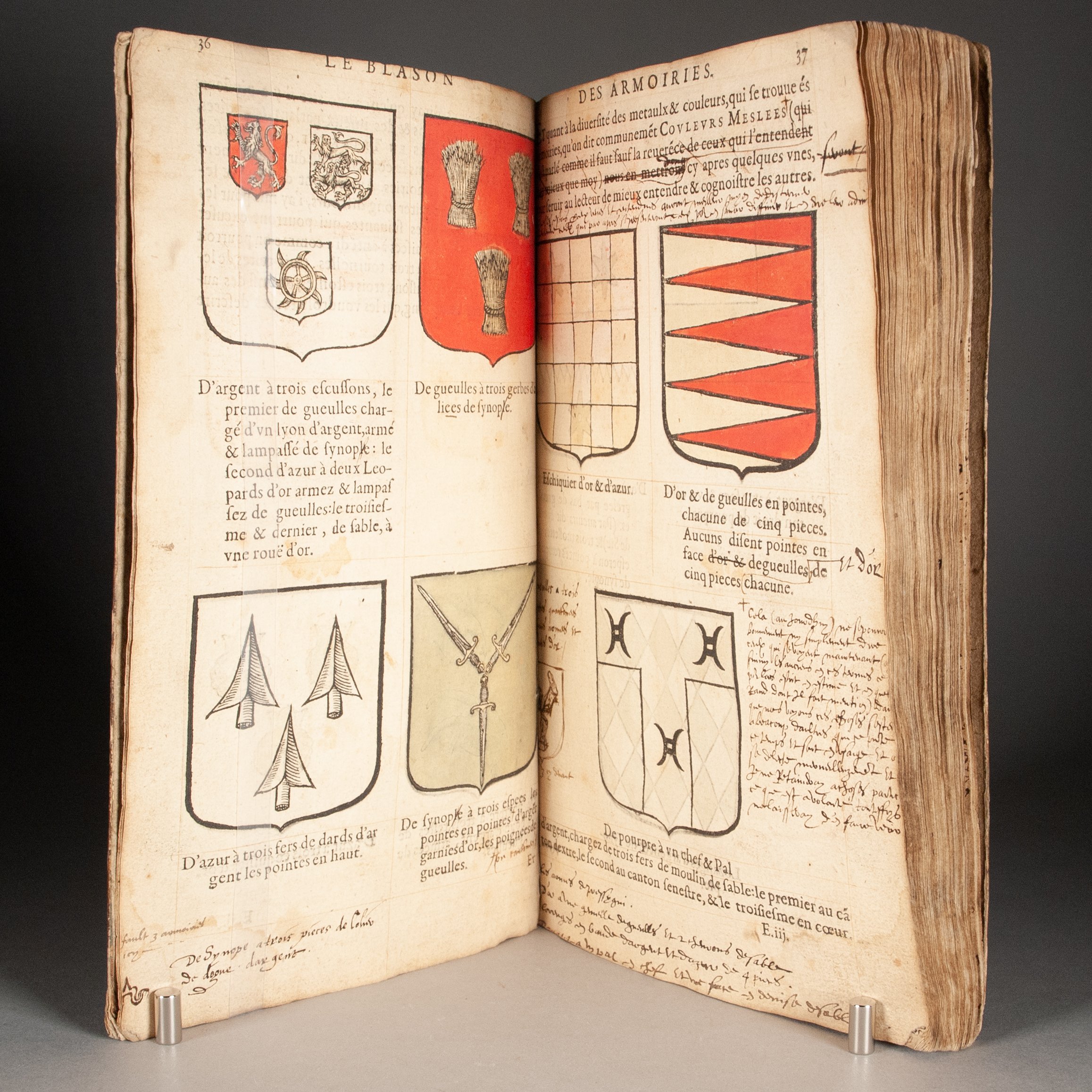

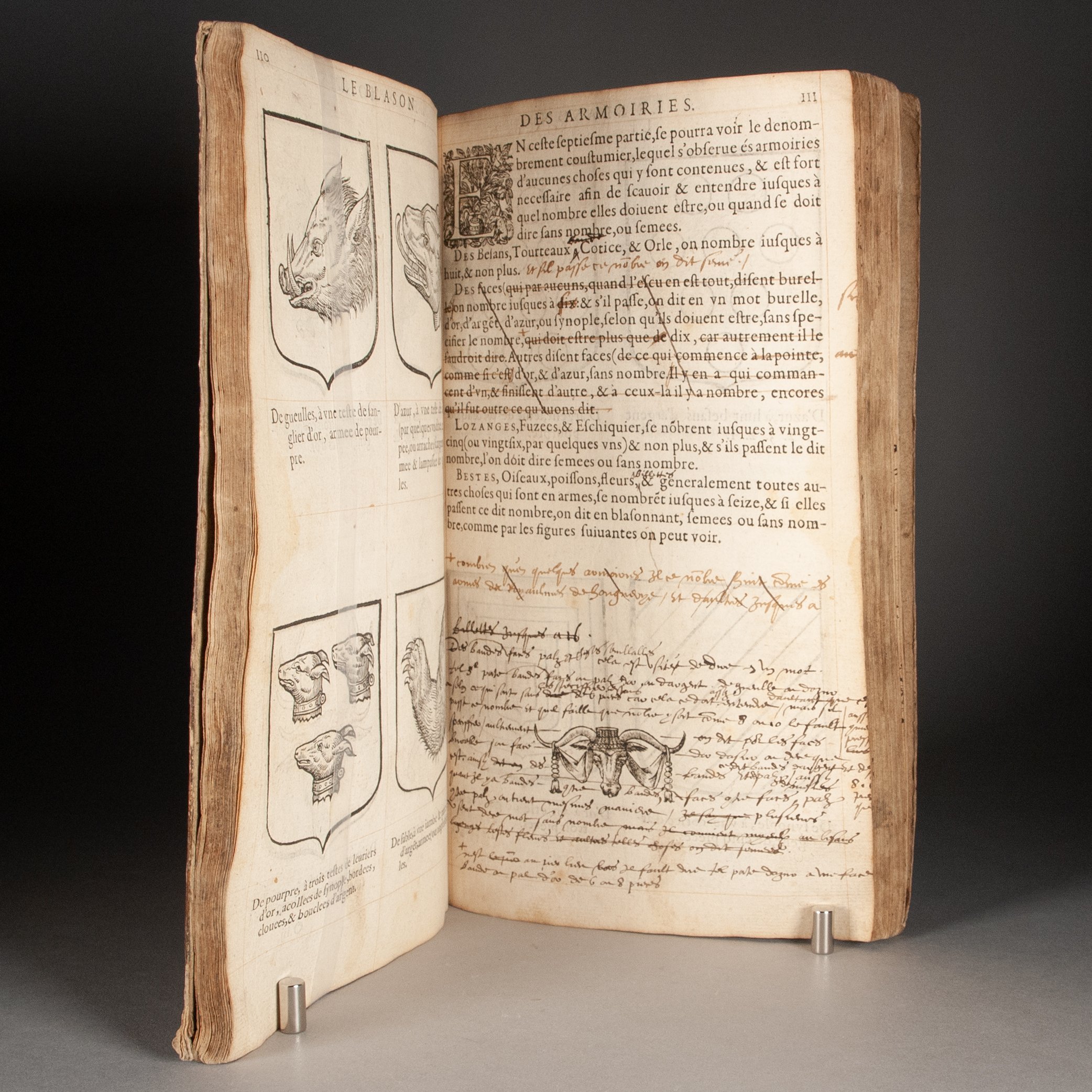

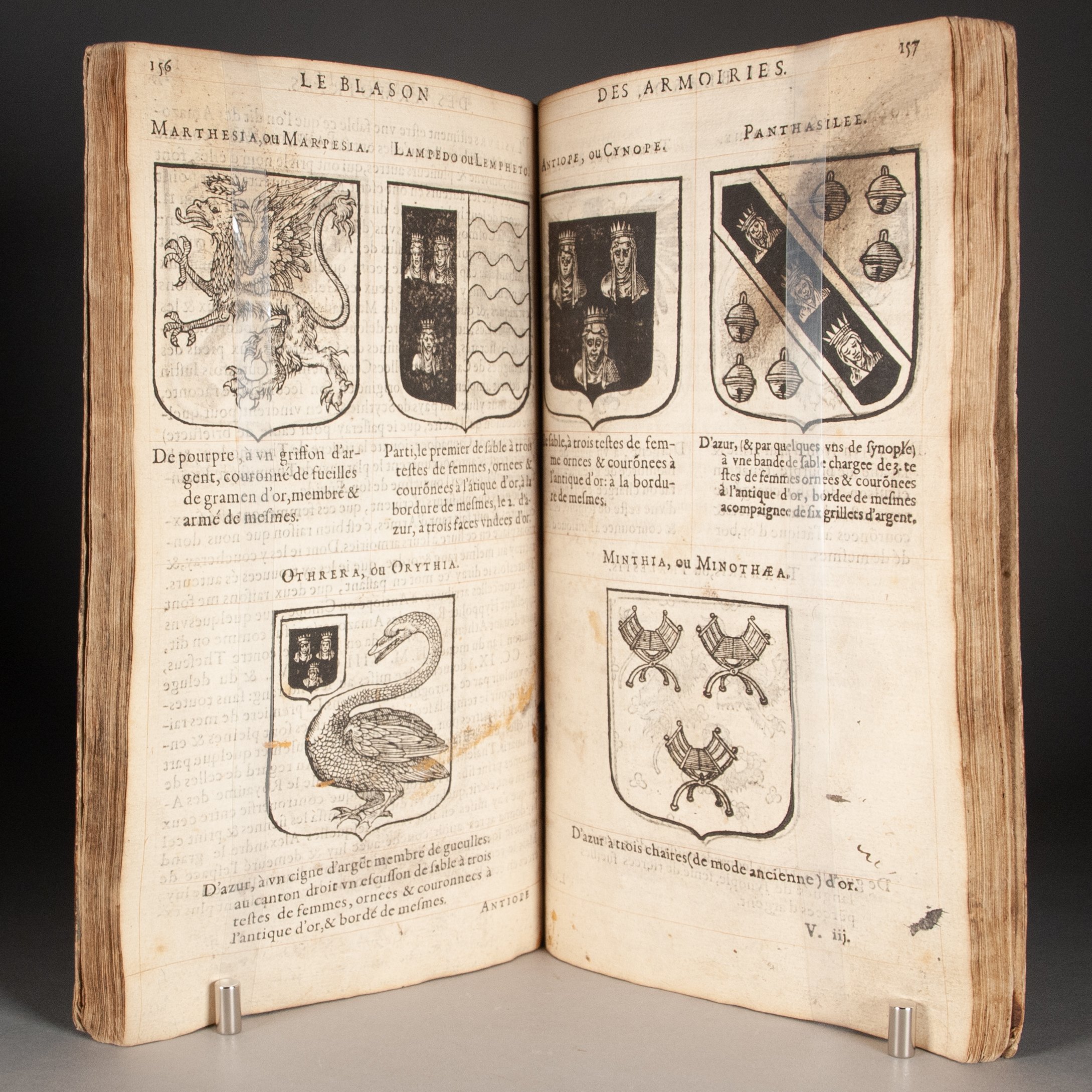

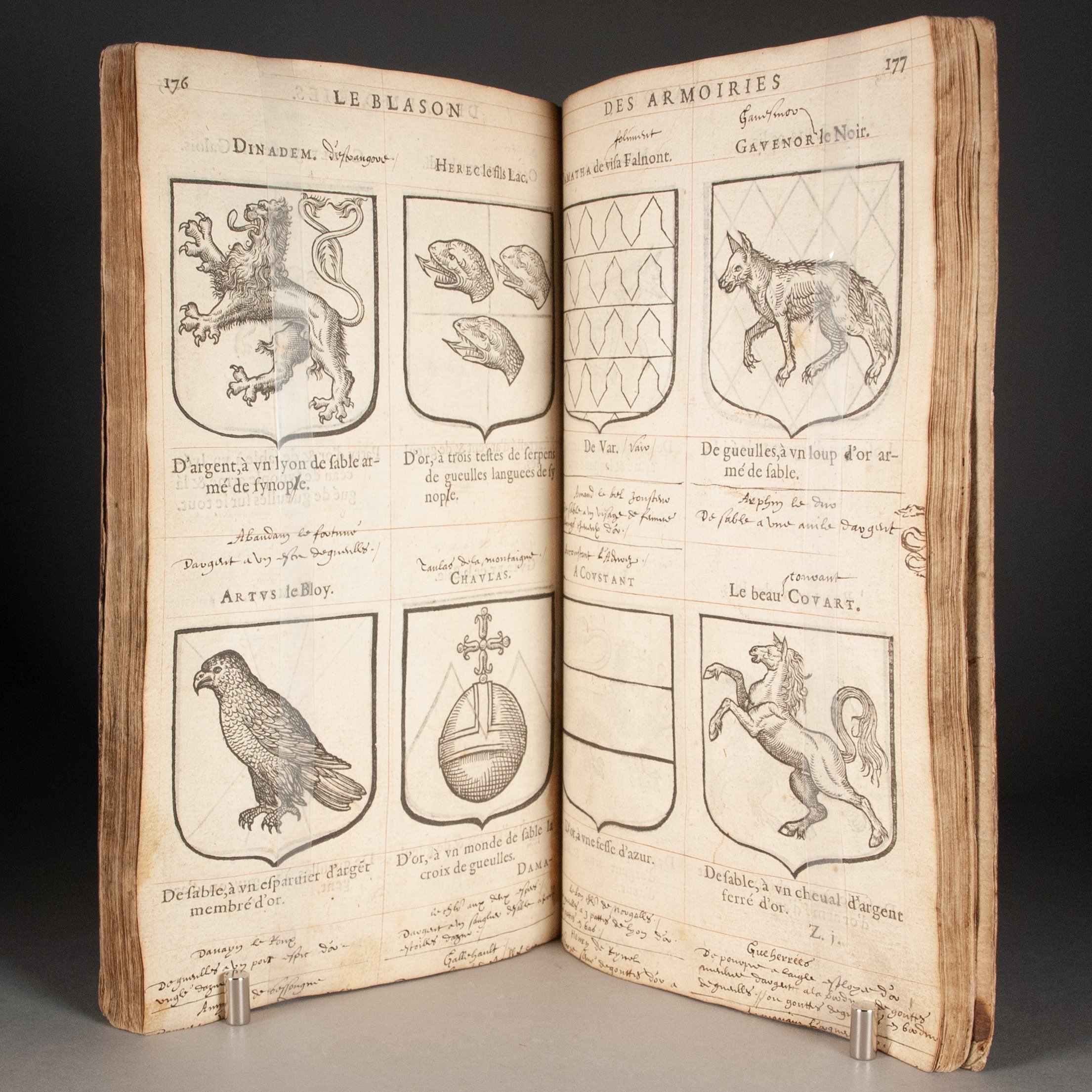

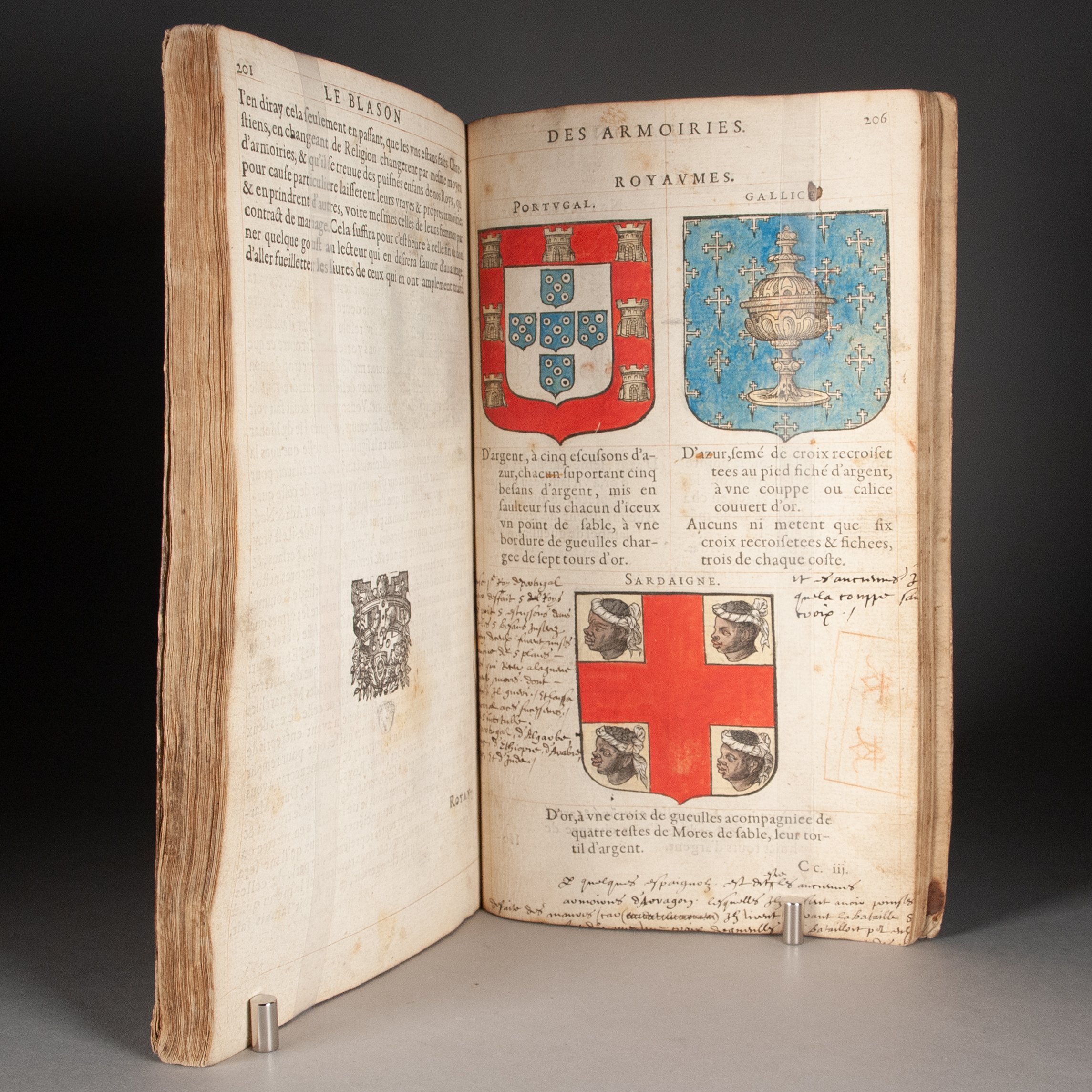

The fifth edition of the French craftsperson's comprehensive treatise on heraldry, first published in 1579, and "one of the period's most significant heraldic handbooks" (Kenny). François Béroalde de Verville claimed credit—and typically receives it—for the commentaries accompanying the illustrations, though commentaire is a rather inexact word. On p. 243 is a sonnet addressed to the reader by Pierre Manson. ¶ Much of the work is dedicated to what are sometimes called imaginary arms, being coats of arms assigned to those who lived before the advent of heraldry. The coverage extends deep into the ancient (and mythical) world, for example, providing arms for the likes of Osiris, Anubis, and Hercules. Imagination aside, the text is fantastically illustrated with DOZENS OF COATS OF ARMS, MORE THAN 90 OF THEM HERE HAND-COLORED, most with only a pale wash to represent gold, but a handful boldly colored in red, blue, and yellow. ¶ In North America, we find this edition only at the Newberry.

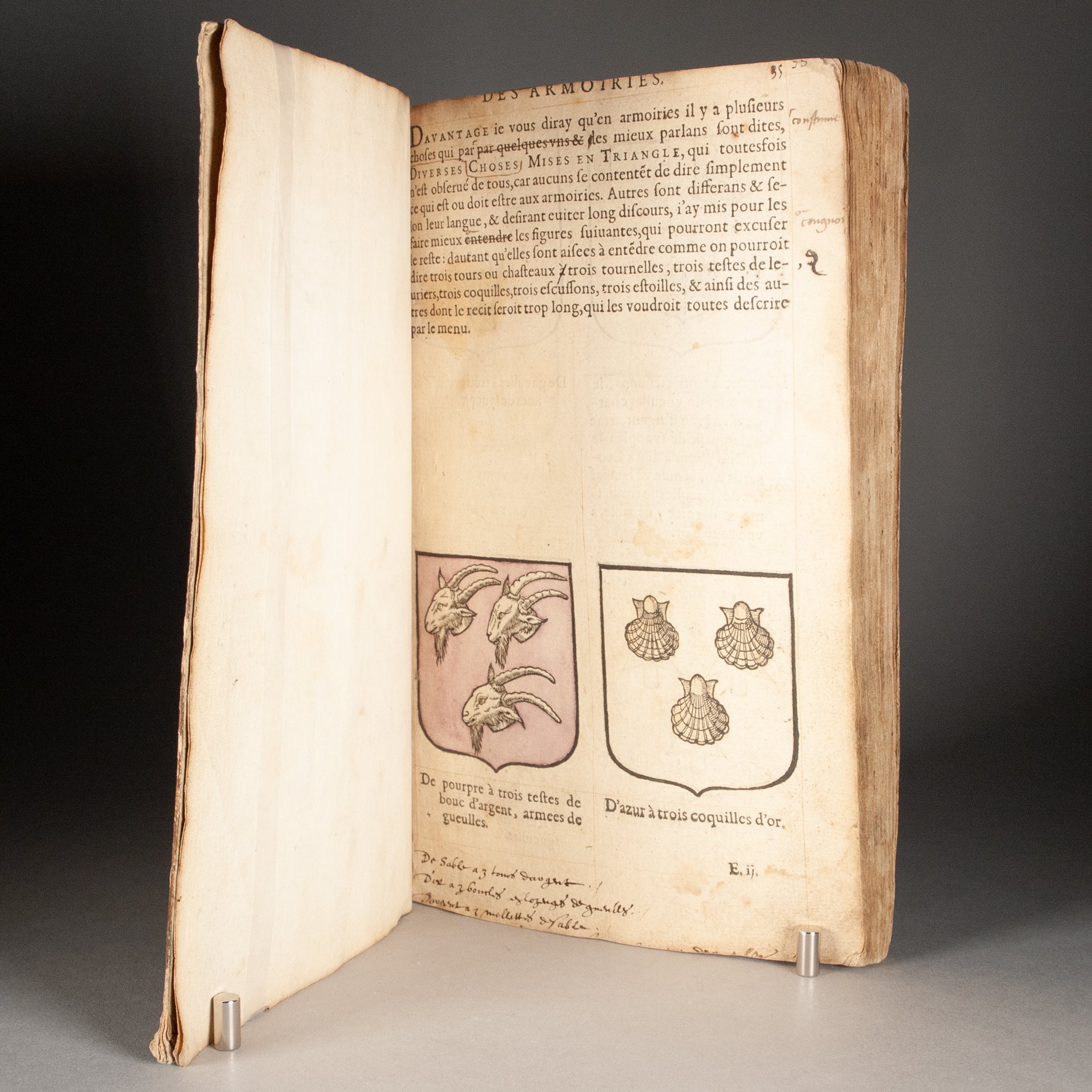

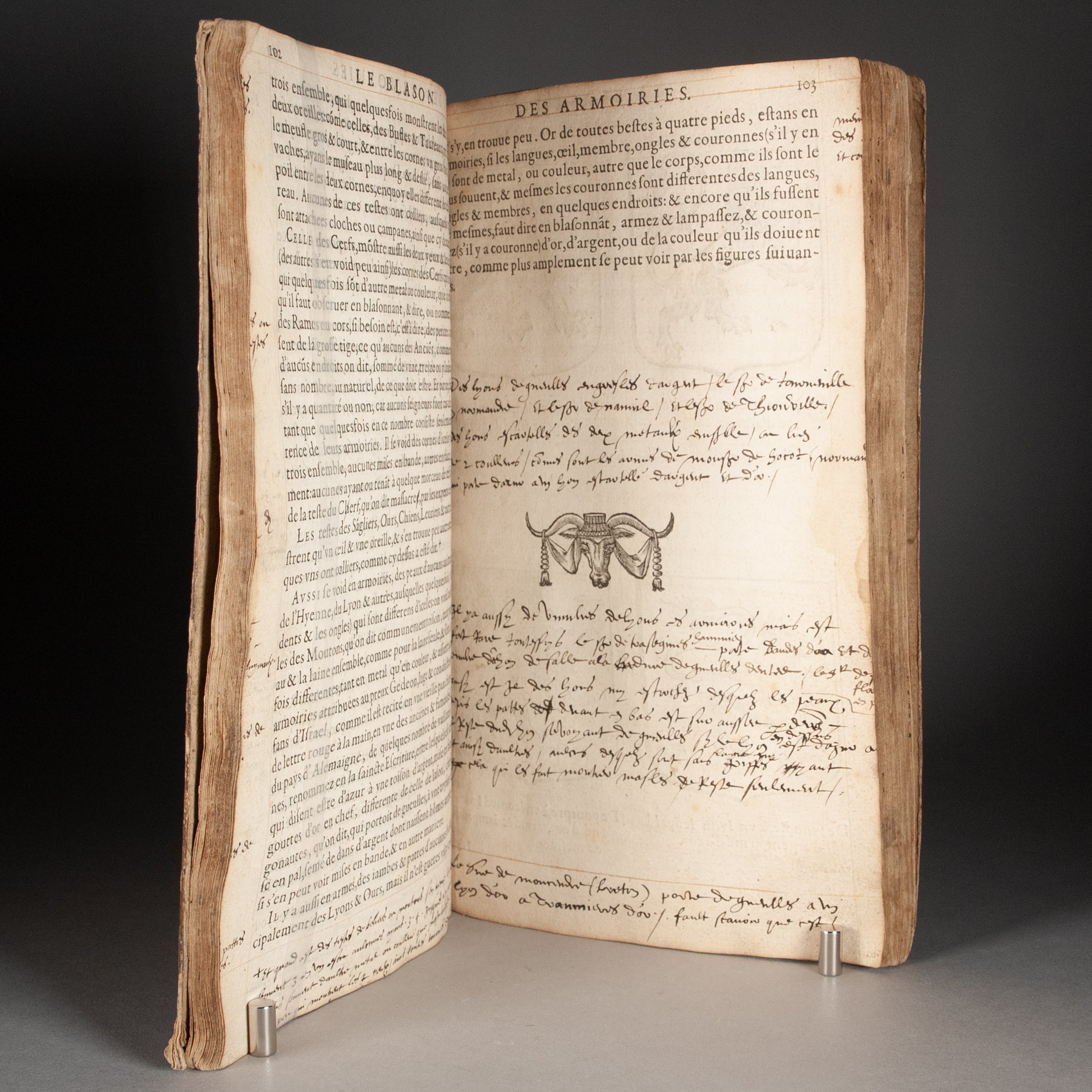

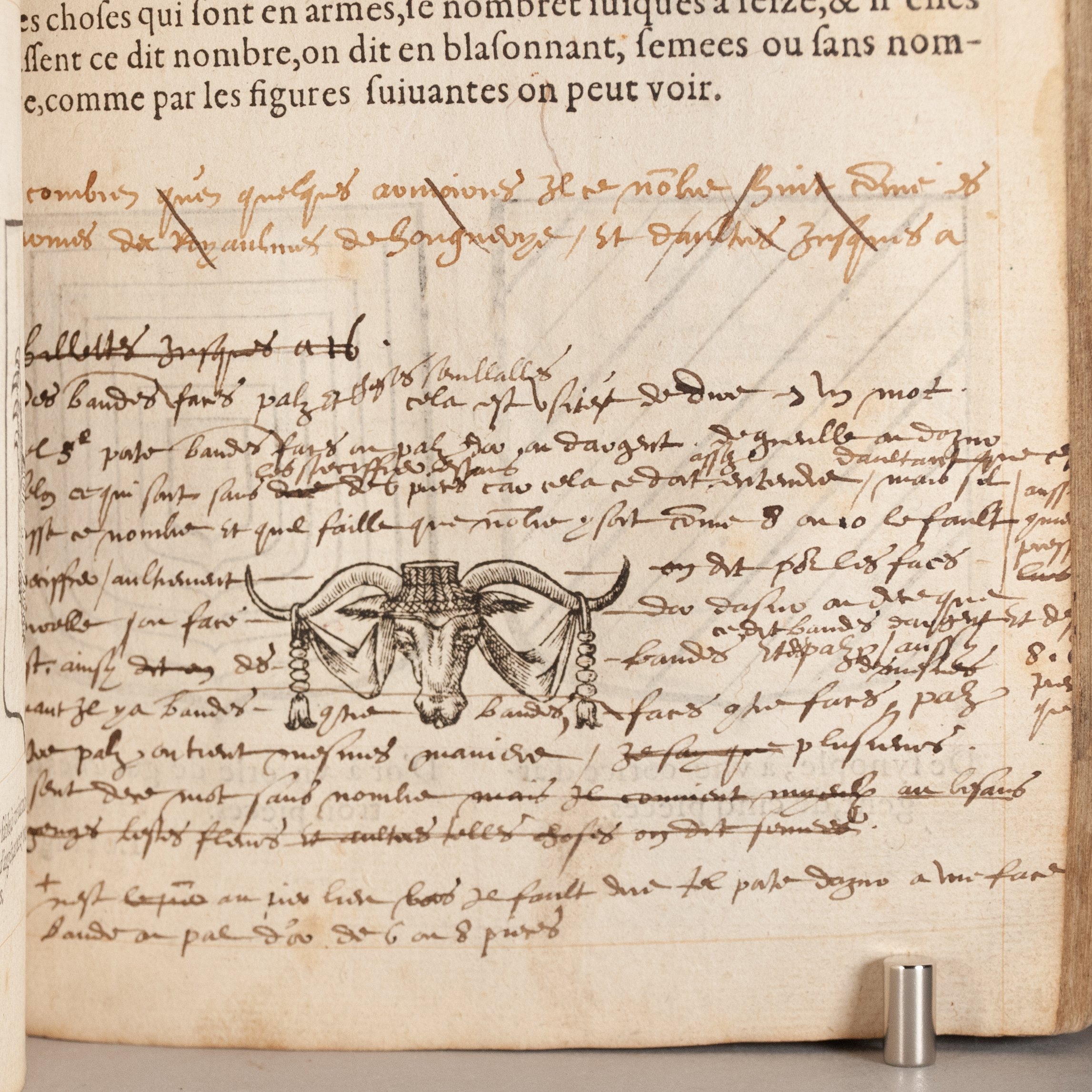

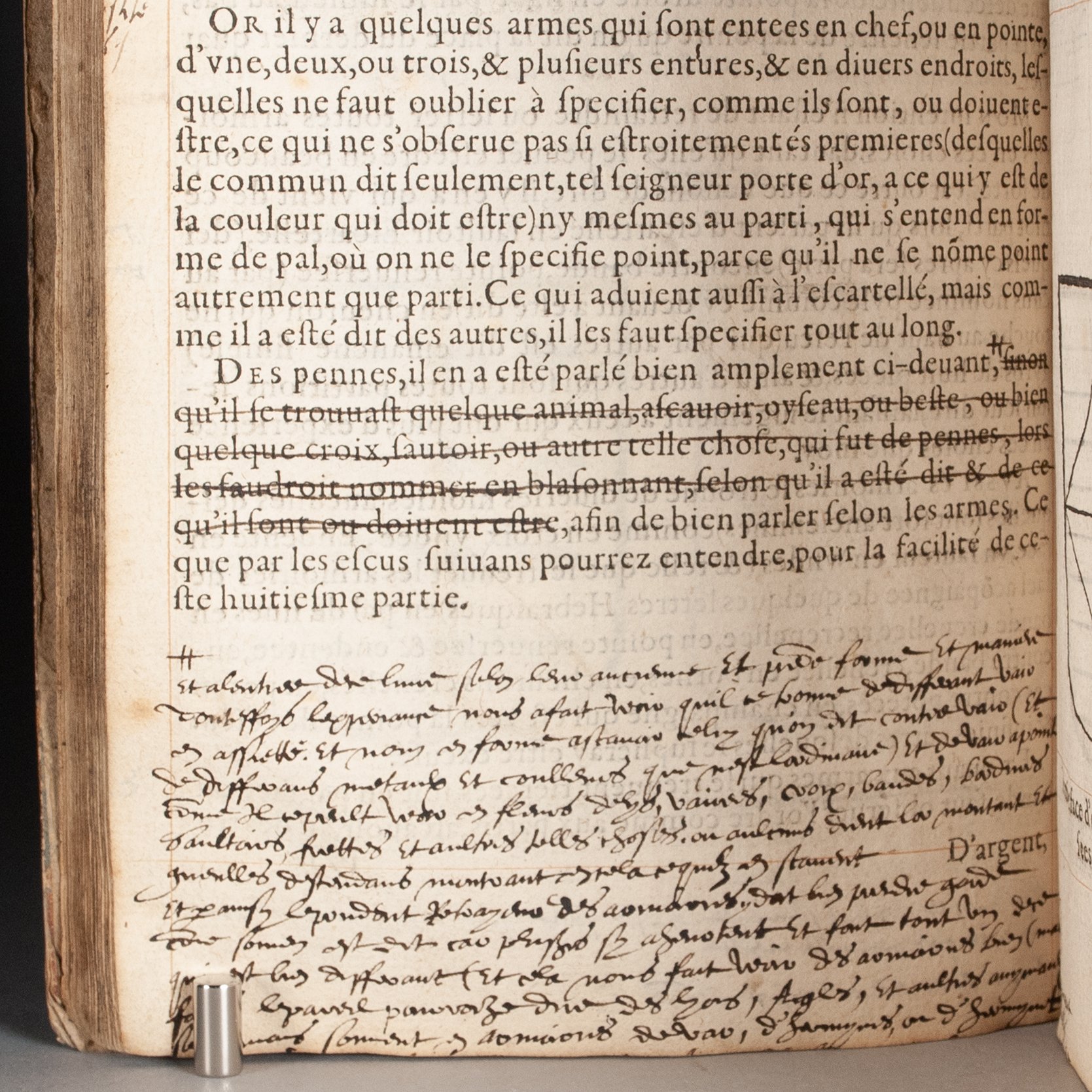

PROVENANCE: Heavily annotated in an early hand, one we'd hesitate to date later than the 17th century, with NEARLY TWO THIRDS OF PAGES CONTAINING SOME LEVEL OF ANNOTATION (and still more containing non-verbal marks). At times, the annotation looks much like proofreading. On p. 35, for example, our annotator makes a note to invert the printed phrase diverses choses, and replace entendre with congnoistre. Such relatively minor textual changes appear throughout, sometimes a full sentence is struck or a new one added, and even paragraph-length additions are not uncommon. But our (spot-checked) handwritten corrections do not appear in the digitized 1604 editions at the Lyon city library and the Hendrik Conscience Heritage Library, suggesting our copy was not a proof for the 1604 edition. Nor do they appear in the next edition, 1628. To be sure, if these annotations do reflect an early owner's ambition to publish something similar—we note especially their handwritten fin du premier livre du blason on p. 135, and fin du deuxiesme on p. 199—we've found no evidence that it ever came to press. ¶ Whatever the intent, the annotations are clearly the work of someone well versed in the terminology and traditions of heraldry. The vast majority revise and expand upon printed descriptions of coats of arms. On p. 172, for example, we find an annotation elucidating a description of a lion in certain colors: cest un leopard lyonné. A marginal note at the foot of p. 102 expands on the meaning of animal heads in heraldry (Et quand est des testes...). Our annotator frequently corrects colors the author provides (for example, see pourpre corrected to gueulles on p. 82). On p. 142, they provide descriptions of missing arms for Castor and Pollux. It's possible our reader may be pulling some of this information from elsewhere in the printed text. But scattered evidence suggests much of it comes from the annotator's own knowledge and additional reading. They sometimes comment on others' descriptions (aultre dit...), and they cited printed works of 1549 and 1584 on p. 245. Even incomplete, this copy provides the portrait of an early reader with a thorough knowledge of heraldry—more knowledgeable, perhaps, than the author himself. ¶ The lines of a fleur de lys on p. 30 and a cow on p. 222 have been DELICATELY PRICKED, PRESUMABLY FOR POUNCING. This was an early method of transferring designs, used across a breadth of different trades. A thin powder could be rubbed through the fine holes, leaving a copy of the design on any material placed beneath it. ¶ Old ownership signature of one G. Perruchot on front fly-leaf; remnants of an engraved bookplate on front paste-down.

CONDITION: Old marbled paper over flexible paste board. Leaf H4 was likely blank, also missing from the digitized copy at Lyon's public library; errata preserved on leaf H3v. Ruled in red throughout. ¶ Lacking all before p. 37, including [12] pages of prelims, the title page among them, plus three leaves from the 2C gathering; cropped close, affecting many annotations; X and Y gatherings stained; pricking on p. 30 extends through several leaves; moderately soiled throughout. Binding worn, with many tears in the marbled paper; marbled paper soiled. Despite appearances, it's holding together very well.

REFERENCES: USTC 6900497 ¶ Neil Kenny, Born to Write: Literary Families and Social Hierarchy in Early Modern France (2020), p. 331 (cited above, and for Verville's credit: "He provided the commentaries to accompany Bara's illustrations"); Gilles Polizzi, "Fantômes et contrefaçons dans l'oeuvre de Béroalde de Verville: ouvrages virtuels, fictifs et fictionnels," Renaissance and Reformation 34.3 (Summer 2011), p. 97 (more on Verville, including his presence in Manson's poem on p. 243); Mayumi Ikeda, "Labour-Saving or Labour-Demanding? Replicating the Illumination of the 1549 Durandus," The Library 7th Series 25.3 (Sept 2024), p. 322 (pouncing, "a common design transfer method used in various trades, from embroidery to such large works as frescoes")

Item #540