Illuminated bestseller in Koberger binding

Illuminated bestseller in Koberger binding

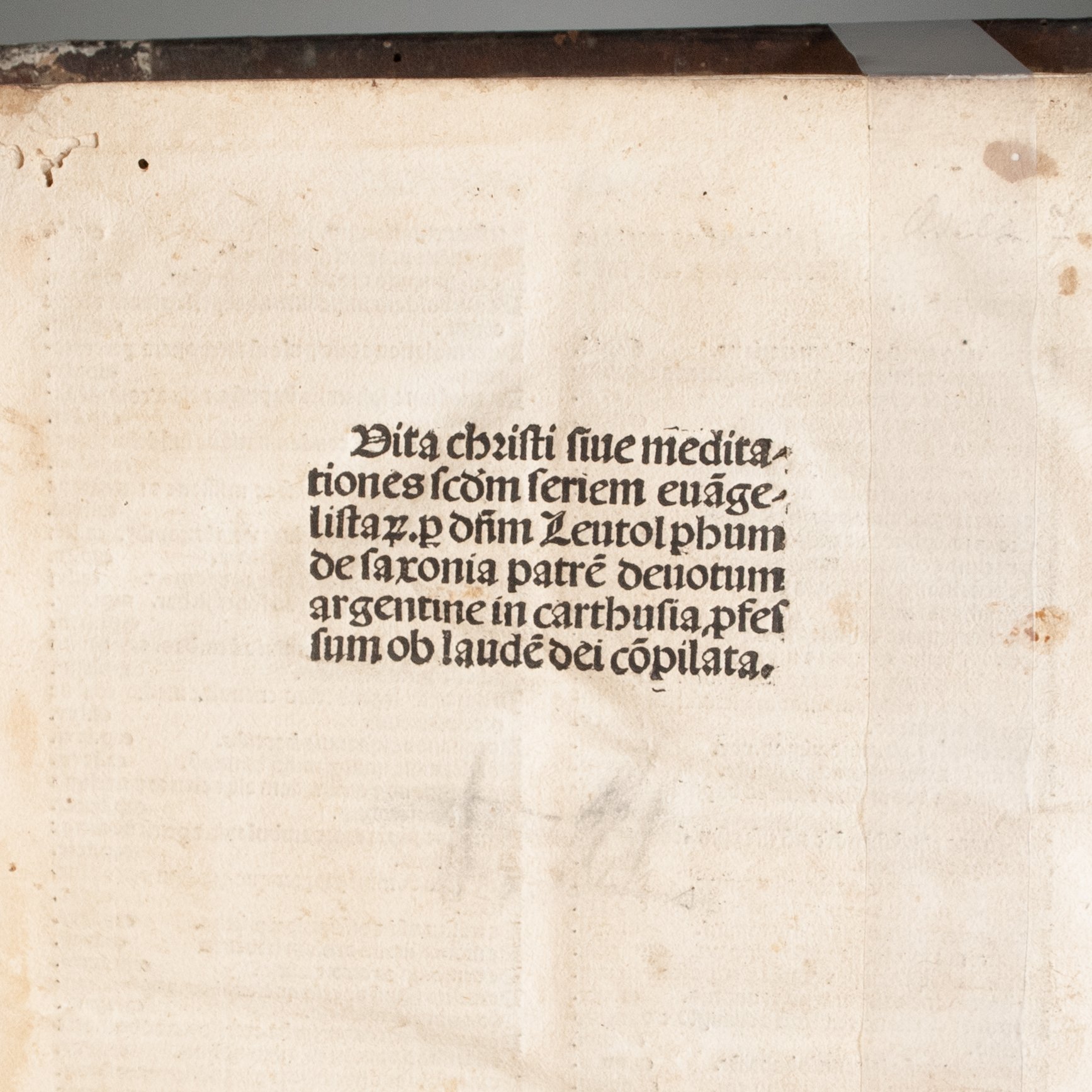

Vita Christi, sive, Meditationes s[e]c[un]d[u]m seriem eva[n]gelista[rum] p[er] d[omi]n[u]m Leutolphum de Saxonia patre[m] devotum Argentine in Carthusia p[ro]fessum ob laude[m] co[m]pilata

by Ludolphus of Saxony (Ludolf de Saxonia)

Nuremberg: Anton Koberger, 14 August 1495

[312] of [312] leaves | Large quarto | A-Z^8 a-q^8 | 338 x 227 mm

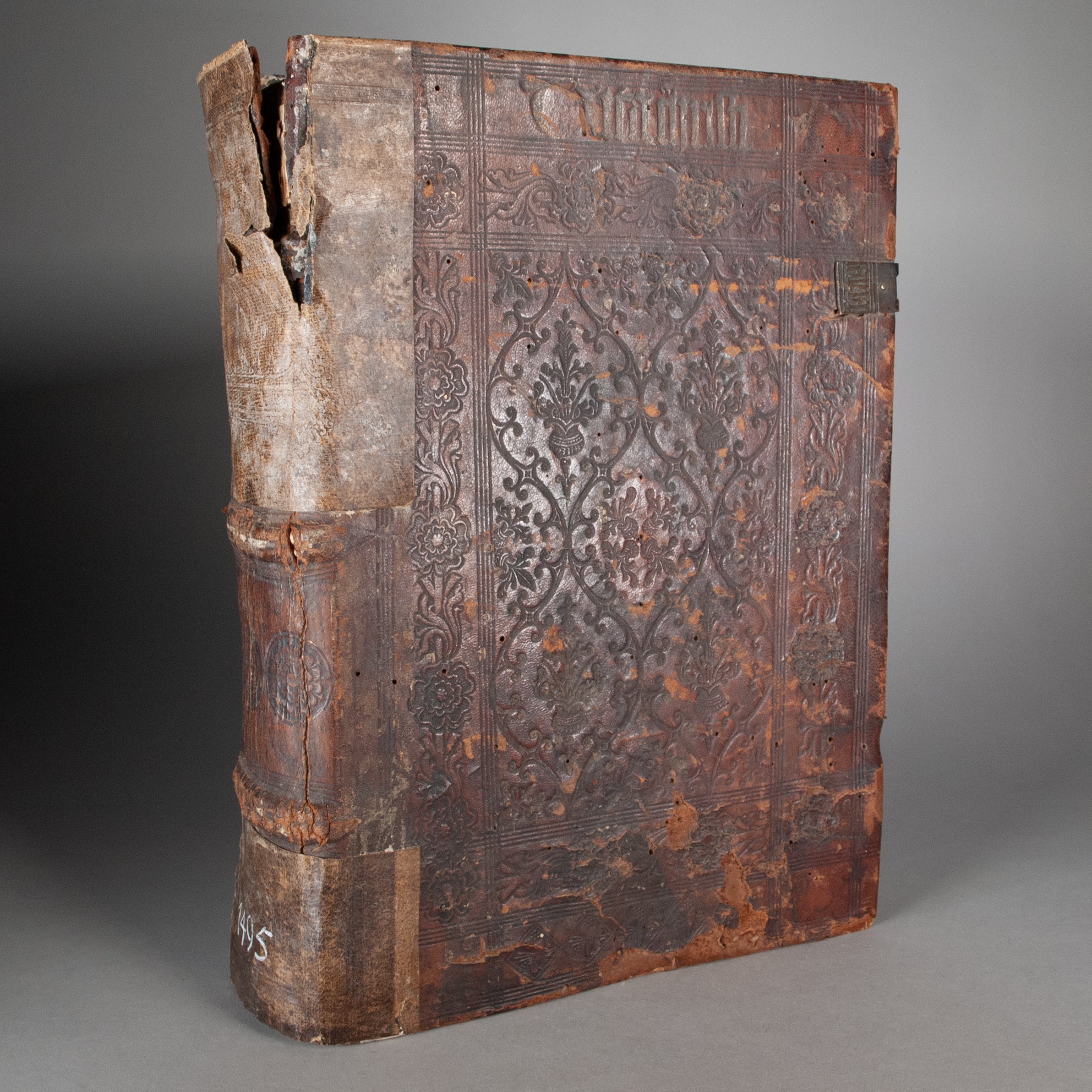

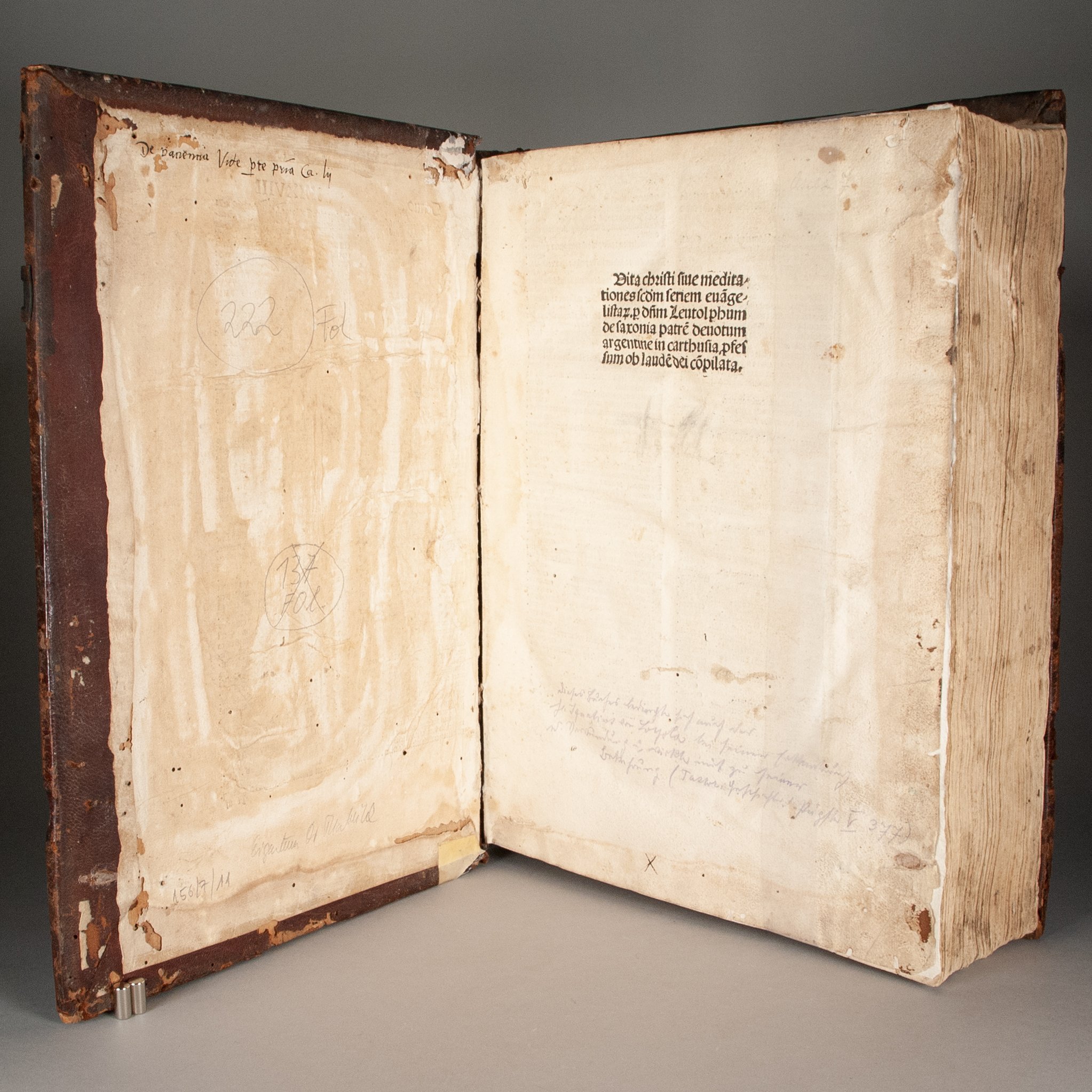

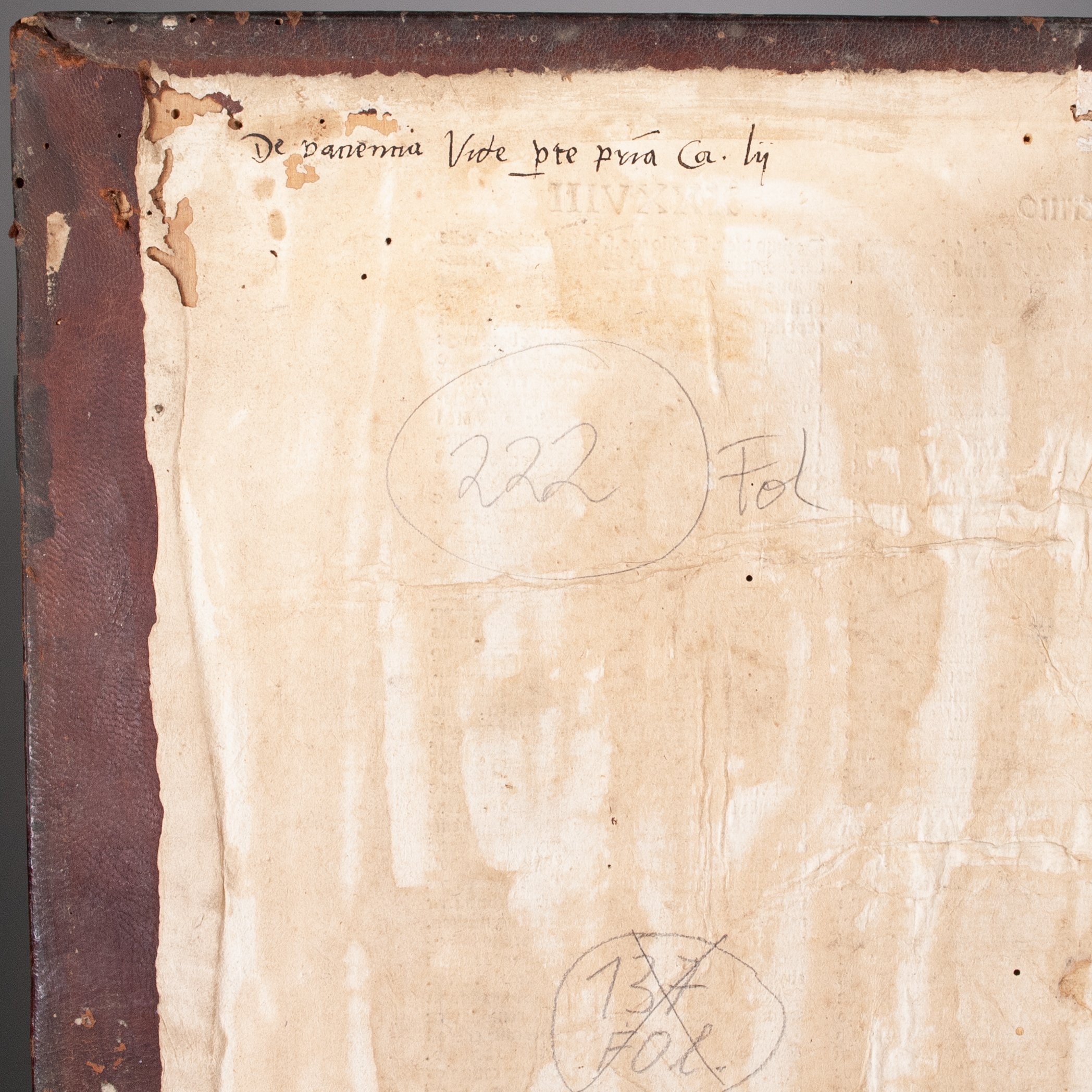

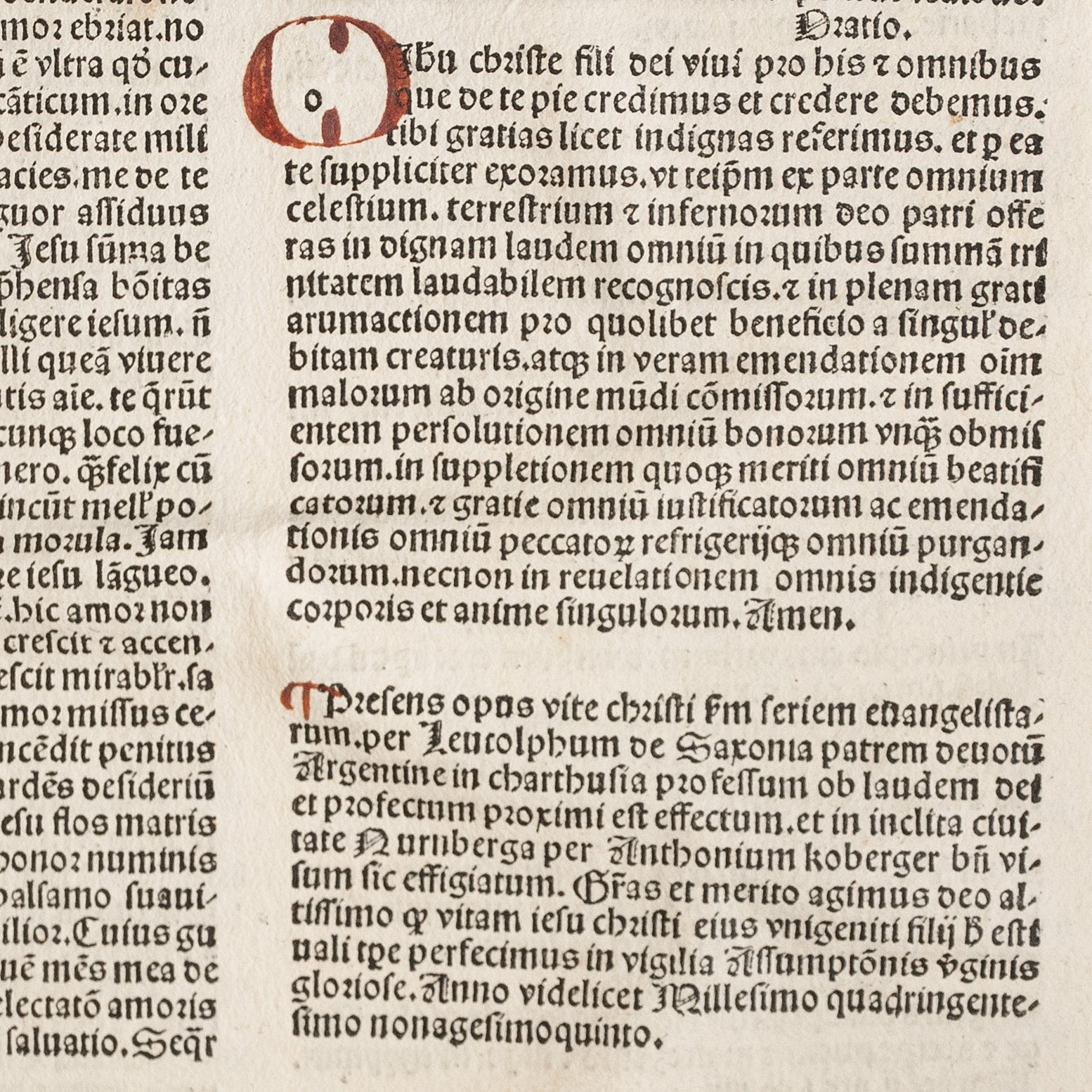

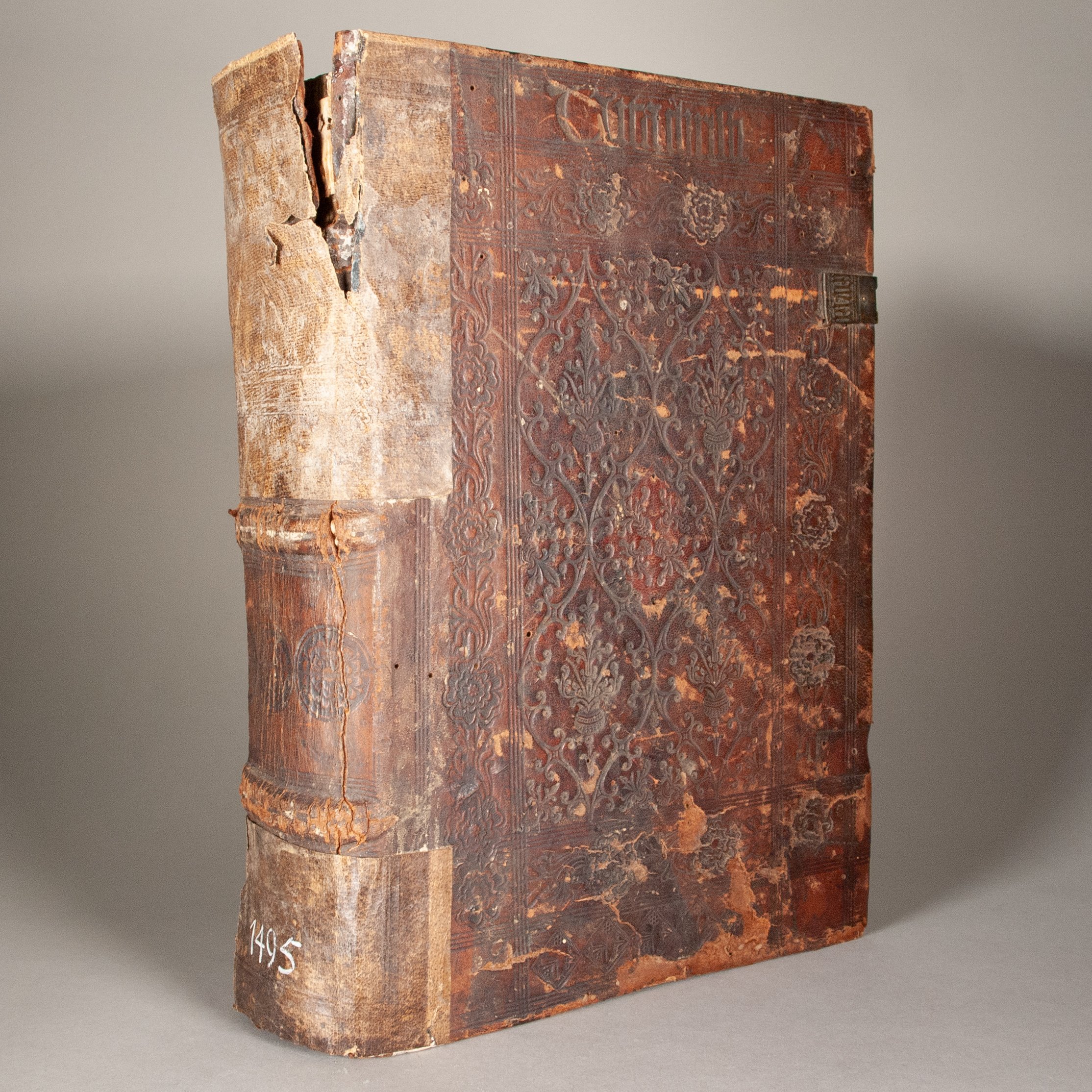

A later incunabular edition of a tremendously popular 14th-century devotional text, first printed around 1472 and reprinted nearly three dozen times by the end of the 15th century. This is Koberger's third and final edition. Ludolphus's Life of Christ was arguably the most successful and most influential contribution to vast vitae Christi genre, certainly in the later Middle Ages. If it competed with anything, it would have been the earlier pseudo-Bonaventuran Meditationes Vitae Christi. The Meditationes certainly influenced Ludolphus's work, but his was a more sweeping and intellectually ambitious text. ¶ Though naturally broader in scope than a passional—Ludolphus draws on the complete series of events in Jesus's life—he does of course include the Passion, that cardinal sequence of suffering. This underscores the typical goal of any life of Christ, not simply to provide some kind of CV for Jesus, but to help readers share in his pain and, through that mutual suffering, facilitate their own salvation. And Ludolphus really encourages his readers to share in Christ's pain. "The exercises contained in the actus go beyond sensory imagination and direct the reader to experience Christ's suffering on her or his own body. For example, to understand the pain suffered by Christ during his captors' mocking, Ludolf suggests slapping oneself. By digging into one's scalp with one's fingernails, one can experience the sharp pricks of the crown of thorns. After a lengthy excursus on Christ's scourging, Ludolph even advises the reader to castigate him- or herself with a whip or switch, at least in thought" (Ehrstine). St. Ignatius of Loyola credited Ludolphus with his own spiritual transformation. During a post-surgical convalescence, he requested some popular romance to help pass the time. As there was no such book available, he was instead served a diet of devotional texts. That time spent reading Ludolphus was the impetus for his lifelong devotion to God, and put him on the path to founding the Society of Jesus. ¶ If his text is more than a passional, it's also more than simply a biography of Jesus. Ludolphus tapped not just vita Christi predecessors like the Meditationes, but the whole gamut of Church Fathers and scholastic commentators, offering "interpretations on all levels recognized by the mediaeval church. A full and unassailable bringing together of facts, doctrines and meanings, unified by the vigorous reflections of the author himself, it has a comprehensiveness and sobriety of general character unlike the predominantly emotional, colourful Meditationes" (Salter). It's a veritable summa of the Church, something Edoardo Barbieri calls "one of the greatest syntheses of the patristic literature." ¶ Here in a contemporary Nuremberg bindingfrom the workshop of Blumenstock II (active 1476-1516), dark brown leather over thick wooden boards, consistent with the style of a Koberger Binding. The front cover has the title stamped at top (Vita christi, just faint traces of gold remaining), a thick border assembled from foliage wrapped around a forked branch (s014018 or s005823) paired with an open rosette tool (EBDB s014012), this surrounding a central panel decorated with four impressions of a curving tendril botanical plate (109792s or p001311); at the very bottom of the front board is a row of pierced hearts (s014007 or s005227). The rear cover has the same rosette and foliage border as the front, but its central panel instead decorated with two intersecting quadruple fillets, each of the four triangular compartments stamped with a griffin (s004896 or s014008). The spine—at least its one visible compartment—is decorated with an encircled rosette tool (s014011 or s007605). ¶ Bindings in this style are often called Koberger Bindings, on the belief that their makers were working for the publisher. It's a difficult thing to prove, but not unreasonable in our case. Koberger did enlist the services of multiple local binders. In fact, Blumenstock II bound so many copies of the Nuremberg Chronicle that he's also known as the Weltchronik Meister. And surely there's no shortage of Koberger imprints in bindings like this, namely with a rosette and foliate border surrounding a central botanical tendril panel, often peppered with griffin stamps. Strengthening the case here are leaves of printed waste lining the boards (though only the left half of the rear board is lined with printed waste, the right half using unprinted paper). That leaf lining the front board is leaf Ff3 from a collection of sermons, its printed recto facing the board, its unperfected verso facing us. As the verso was almost certainly meant to carry text, too—its final line is fully justified—this leaf is very likely a proof. The leaf's types are strong matches for those Koberger used in our Ludolphus (130G and 74G); its text type has a 20-line measurement of ~74 mm. While we're unable to confidently rule out very similar types used by Amerbach in Basel, and while there are certainly examples of printer's waste traveling far afield before winding up in a binding, the Nuremberg binding may reasonably give the edge to Nuremberg waste. And if our binder had access to unpublished waste from Koberger's presses, it helps make the case for a close connection with the Koberger enterprise. ¶ A late medieval best seller from one of the greatest 15th-century presses, in a contemporary Nuremberg binding lined with probable proofs, with some contemporary annotation and a dazzling illuminated initial. This is truly the complete incunabular package. We find only two Blumenstock II/Weltchronik Meister bindings in auction records: at Bloomsbury in 1985, and an incredible hand-colored Nuremberg Chronicle at Bonhams in 2020.

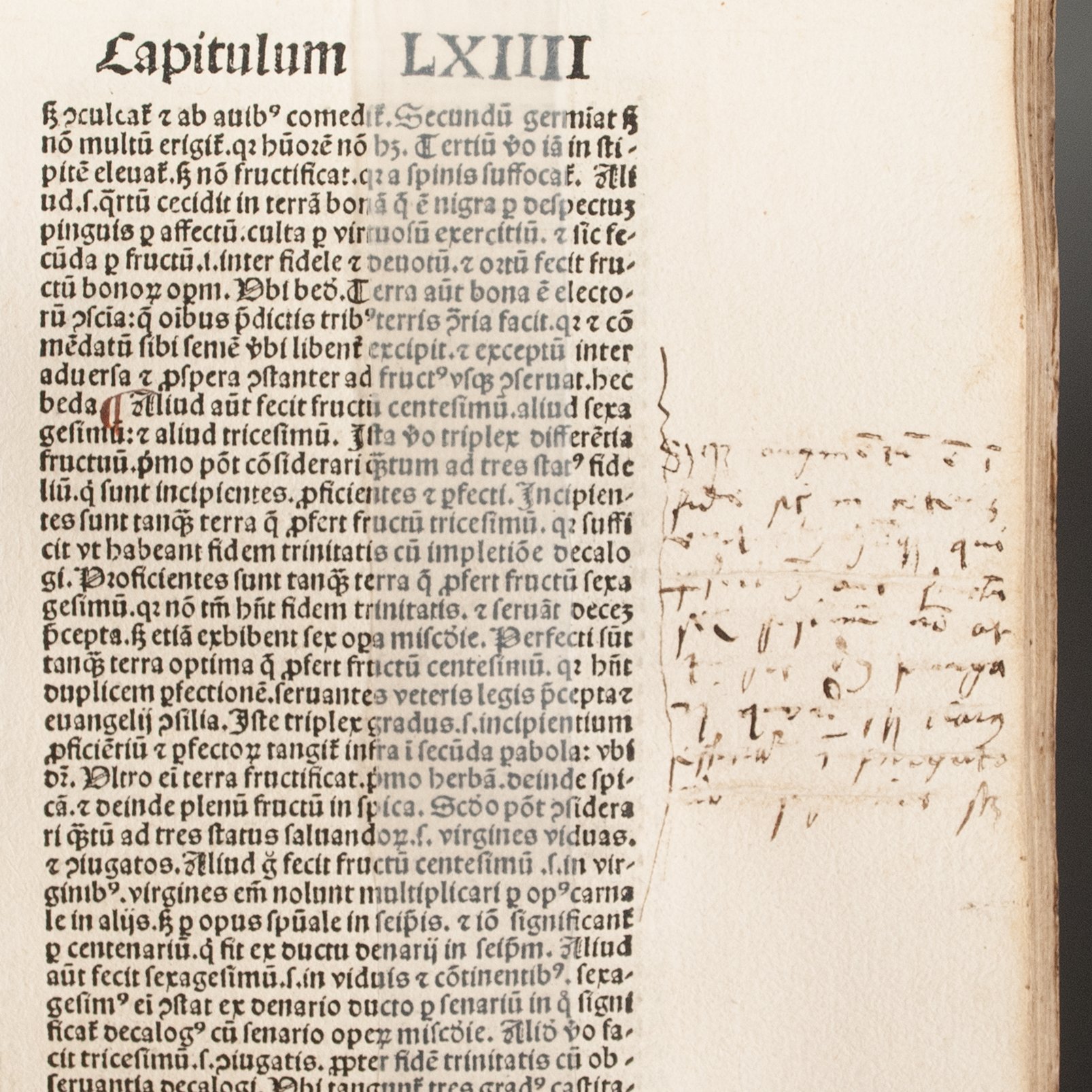

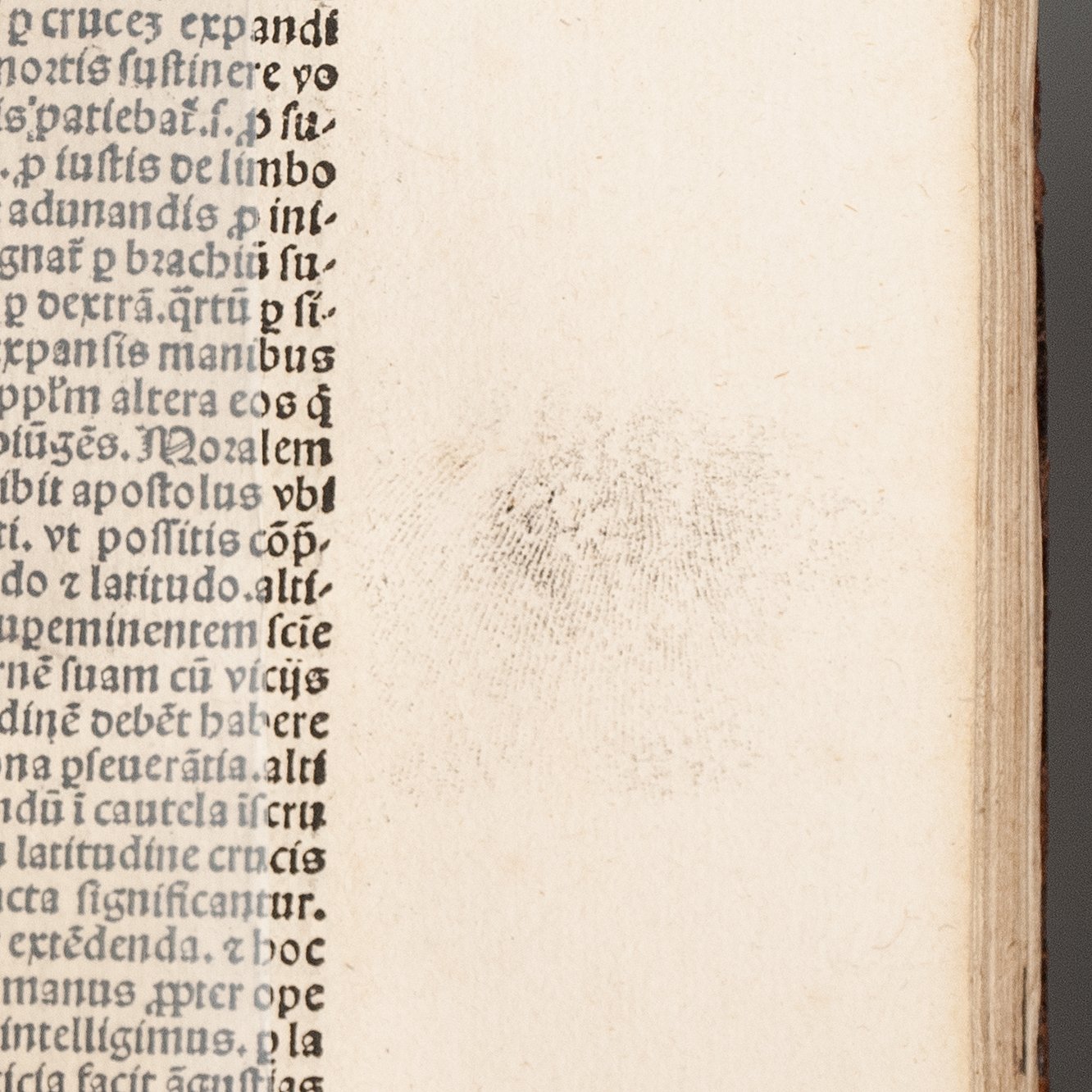

PROVENANCE: With a handful of early annotations scattered throughout, in at least two different hands, some of them several lines long. One early reader largely reinforces desired take-aways from the printed text. On D6r, for example, where Ludolphus mentions that people often remember Jesus in difficult times but abandon him (proditur) in good times, this reader agrees in the margin: "This is not to be rejected, that Christ is kept in adversity but just so dismissed in prosperity" (Non est reiiciendum hoc, quod Christus in adversis custoditur in prosperis vero amittatur). Most intriguing, this reader's annotation on O7r has been partially, but very noticeably, scraped away. We can't make out the handwritten comment, but it remarks on the concept of three different levels of faithful: Incipientes, Proficientes, and Perfecti, which variously require belief in the Holy Trinity and the performance of Good Works. Another early reader appears to have taken broader interest, and perhaps at times more personal. On y4r, for example, they find in Ludolphus "a most beneficial doctrine against despair" (Contra desperationem saluberrima doctrina), and highlight further words of comfort (Pectam preterita non nocent si non placent). ¶ On f8v and g1r, a reader appears to have marked passages of interest in drypoint, perhaps with the scratch of an uninked pen. Part of an inky handprint on k5r, someone in the printing shop we suspect, as the ink is the same color as the text and there are no annotations in the vicinity. A couple of wax drops on Z2v and Z3r. Some brief notes scrawled on the paste-downs and title, some old and some more recent, some devotional and some bibliographical.

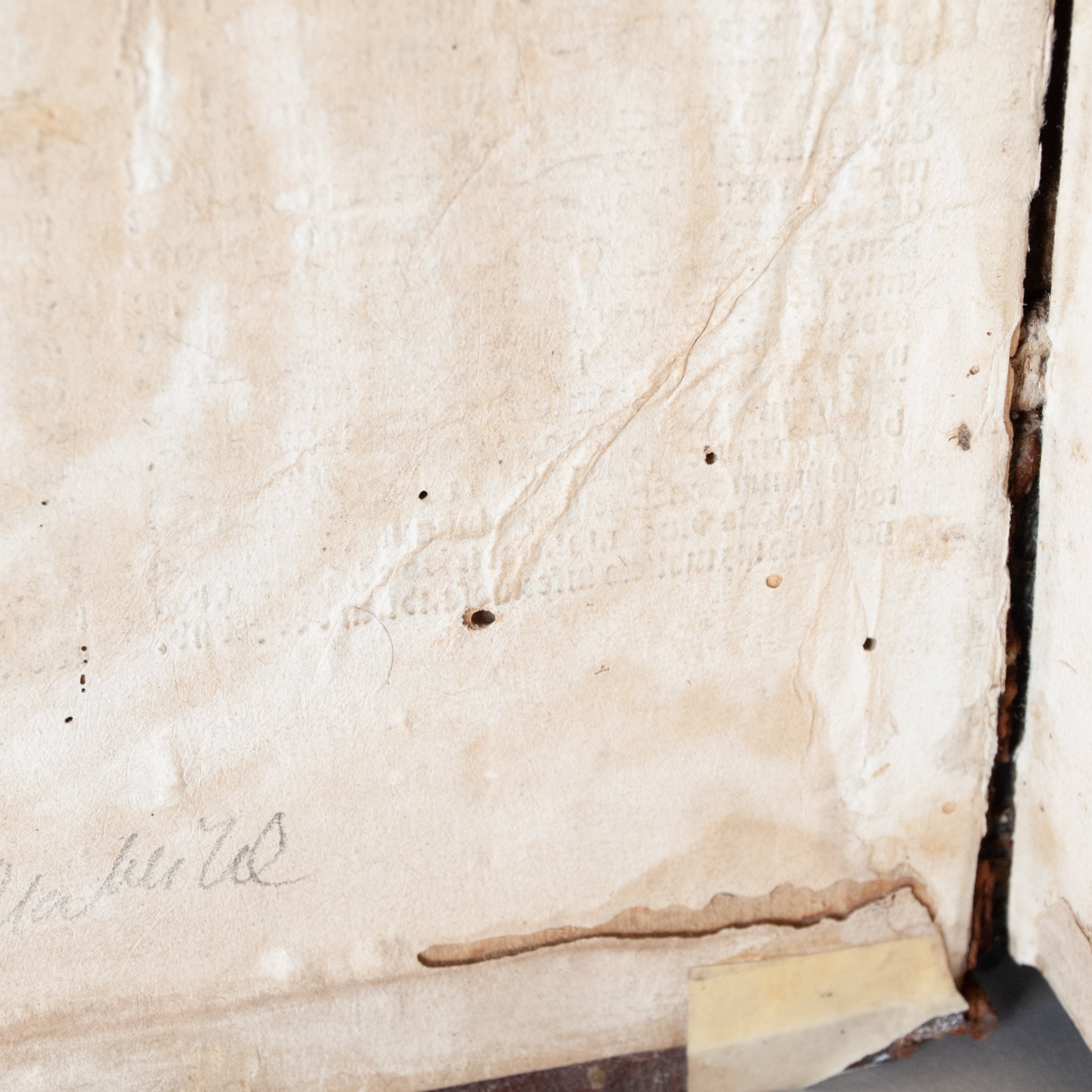

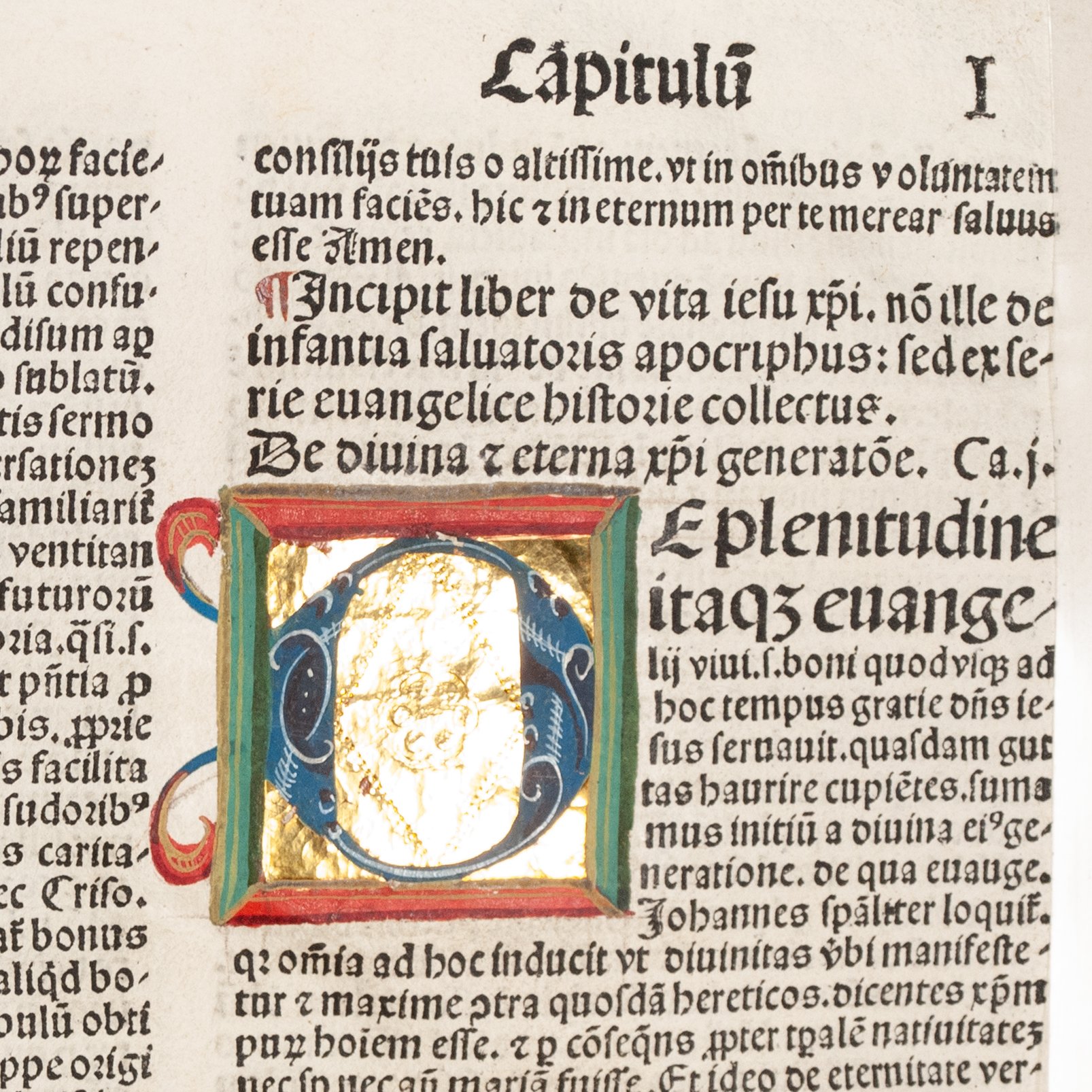

CONDITION: Contemporary Nuremberg binding of brown leather over thick wooden boards, as described above; one remaining brass catch for a clasp. With a large illuminated initial D on A4r in blue, red, green, black, and white, on a dazzling ground of burnished gold leaf, doubtless local Nuremberg work (we've seen a very similar illuminated D in a 1483 Koberger Bible). With countless pilcrows added by hand in red, numerous three-line initials in red, and occasional three-line initials in blue. Original sewing often visible at the center of the quires; quite a few deckle edges preserved, but also a témoin in the lower corner of leaf l8. ¶ Scattered worming throughout, mostly marginal; occasional mild soiling; rubrication frequently dulled to a (sometimes sparkly) gray; occasional marginal dampstaining; title ragged at the edges and reinforced on its verso; first dozen leaves with a little marginal loss at the upper fore-edge. Old spine repair using decorated parchment, perhaps taken from another medium, as it looks unlike book decoration (these repairs now heavily torn themselves); lower corner of rear board repaired; leather generally worn, with worming and occasional loss, especially at the bottom of the front board; clasps, corner pieces, and central bosses lost. For all that, a pretty solid, satisfying contemporary binding.

REFERENCES: ISTC il00346000; USTC 746772; Catalogue of Books Printed in the XVth Century Now in the British Museum, v. 2, p. 440, IB. 7494 (also reporting red initials and "Original stamped leather, with the inscription: Vitacristi"); Goff, Incunabula in American Libraries, L-346 ¶ On the content: Glenn Ehrstine, "Passion Spectatorship between Private and Public Devotion," Thresholds of Medieval Visual Culture: Liminal Spaces (2012), p. 312 ("Ludolph's treatise exerted widespread influence throughout Europe after its composition in the mid-fourteenth century and eventually became one of the primary sources for the Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius Loyola") 313 (cited above); Elizabeth Salter, "Ludolphus of Saxony and His English Translations," Medium Aevum 33.1 (1964), p. 26 (cited above; "the work rapidly gained fame"); Edoardo Barbieri, "Tradition and Change in the Spiritual Literature of the Cinquecento," Church, Censorship and Culture in Early Modern Italy (2001), p. 122 (“The Vitae Christi—accounts of episodes from Jesus’ life and passion—did not serve an ‘informative’ purpose in the intellectual sense. Rather, they had the ‘formative’ function of enabling the faithful to identify with the experience of Christ. That is to say, these ‘lives of Christ’ marked out a route to salvation which did not necessarily pass through the Bible."), 124 (cited above; “a significant series of events from the life of Jesus, removing their accretions of legend and restoring them to their factual truth. To this plain account he applied a commentary based on the ancient and medieval exegetic tradition. It is of little importance that obtuse criticism has sought to devalue the work’s theological worth and to assert its purely devotional purpose, for it is one of the greatest syntheses of the patristic literature.”); Steffen Zierholz, "'To Make Yourself Present': Jesuit Sacred Space as Enargetic Space," Jesuit Image Theory (2016), p. 425 ("one of the most influential meditation texts of the late Middle Ages. Its significance for Ignatius of Loyola's conversion, as well as for the genesis of the Spiritual Exercises, is well known."); Richard S. Field, "64. Blockbook with the Passion and German Texts," Origins of European Printmaking (2005), p. 222 (“Devotion to the Passion of Christ reached its zenith during the fifteenth century. Pious men and women of all walks of life were deeply committed to the salvation of their souls.”) ¶ On the printer: The Oxford Companion to the Book (2010), v. 2, p. 848 ("He created the then-largest printing enterprise in Germany. His network of trade partners extended to Italy, France, Poland, Austria, and Hungary, and he employed numerous itinerant dealers."); S.H. Steinberg, Five Hundred Years of Printing (1996), p. 25 ("the biggest European printer of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries...He set up shop in 1470 and for a time combined printing, publishing and bookselling. All these things he did on a grand scale...At the height of his activities, Koberger ran 24 presses served by over 100 compositors, proof-readers, pressmen, illuminators and binders.") ¶ On the binding: Einbanddatenbankw001532 (for the Blumenstock II studio; individual tool numbers cited above); Lore Sprandel-Krafft, Die spätgotischen Einbände an den Inkunabeln der Universitätsbibliothek Würzburg (2000), p. 122 (descriptions of other Blumenstock II bindings); E. Ph. Goldschmidt, Gothic & Renaissance Bookbindings (1928), v. 1, p. 166 (describing the binding on a 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle: "There certainly is no doubt that the back cover of this Schedel is as typically 'Koberger' as any of the hundreds of original 'Koberger' bindings I have seen"; "The back cover shows the typical Nürnberg decoration. By way of a frame the staff entwined with foliage, on which at regular intervals the large rosettes are superimposed. The centre panel divided by diagonals into large lozenge-shaped compartments, containing either the scaly griffin...or the heart pierced by an arrow"); Ilse Schunke and Konrad von Rabenau, Die Schwenk-Sammlung gotischer Stempel- und Einbanddurchchreibungen (1996), p. 208 (brief account of the binder, noting his preference for using small plates to produce his tendrilled diamond motif)

Item #824