The West's first Black physician | Likely his earliest obtainable work

The West's first Black physician | Likely his earliest obtainable work

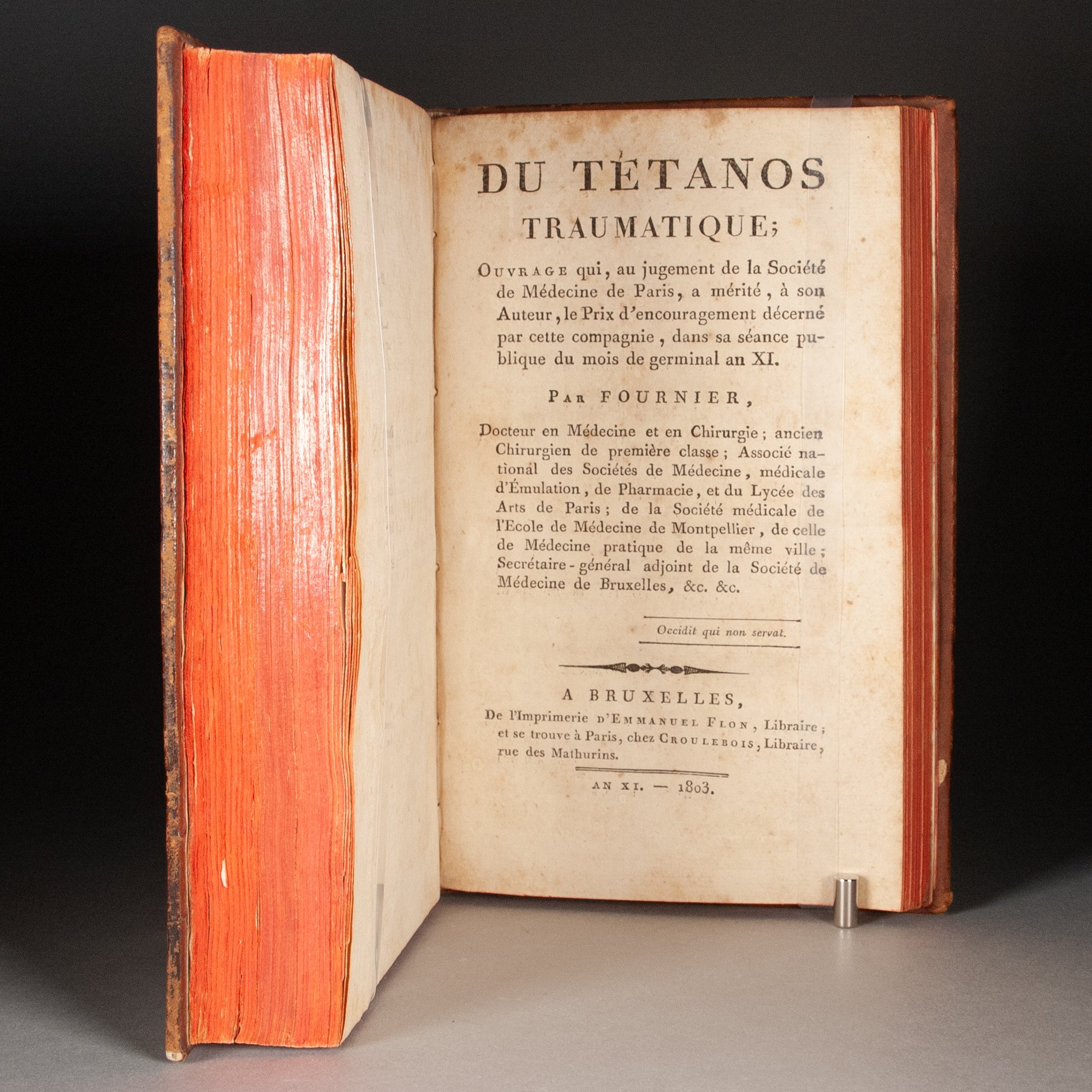

Du tetanos traumatique; ouvrage qui, au jugement de la Société de médecine de Paris, a mérité, à son auteur, le prix d'encouragement décerné par cette compagnie, dans sa séance publique de mois de germinal an XI

by François Fournier-Pescay

Brussels: Printed by Emmanuel Flon for Croulebois, Paris, 1803

xxviii, 86, [2] p. | 8vo | pi^2 a^8 b^4 A-E^8 F^4 | 200 x 121 mm

First edition of the Saint-Domingue-born physician's treatise on tetanus infections in combat, and likely the earliest obtainable work by a western physician of color. Fournier-Pescay published rather prolifically, but only one work preceded the present: his Essai historique et pratique sur l'inoculation de la vaccine, certainly published by 1801—in its fourth edition by an X of the French Republican calendar (September 1802 at the latest)—and quite rare. We find no first-edition copies of his Essai in WorldCat, just two copies of any edition in US libraries (a fourth edition at both Harvard and Duke), no editions in auction records, and just a few early holdings in the Catalogue collectif de France. Our Tétanos traumatique is not much more common. ¶ "Occasionally," trumpets Robert Fikes, "when researching important figures of the past, a person of considerable talent and importance is discovered—a person who, inexplicably, has been confined to the dim attic of history while far less significant figures have for ages basked in the sunlight of notoriety." That is François Fournier-Pescay to the field of medicine. "It is simply a fact that no other physician of African descent was able to accomplish as much during the 18th and 19th centuries, or probably any time prior to the onset of the Industrial Revolution." He was “the first medical doctor of African descent to help found a medical society, to publish medical research, to found a literary and scientific journal, and to become a distinguished administrator and educator at home and abroad” (Fikes). ¶ After studying medicine at Bordeaux, he spent a number of years practicing battlefield medicine for the French army, experience that surely influenced the present work. He then settled in Brussels as professor of pathology, where he co-founded the city's medical society and, in 1803—the same year as our Tétanos treatise—began publishing a journal devoted to the arts and sciences (Le nouvel esprit des journaux). He was personal physician to Ferdinand VII of Spain, was elected secretary to the French army's health council, was given the Legion of Honor's highest accolade by Louis XVIII, and played a role in the founding of the first lycée on Saint-Domingue, the Académie d'Haiti. In becoming Europe's first Black physician, he anticipated the accomplishment of James McCune Smith, the first African American to earn an M.D., by more than forty years. He was without peer, the significance of his path-breaking achievements perhaps best matched by those of Benjamin Banneker. ¶ Fournier-Pescay was born in 1771 to a French planter and Adélaïde Rappau, a free woman of African descent (mulâtresse libre). French law then forbade the couple from marrying, but they nonetheless became a prosperous plantation-owning family in present-day Haiti. Their son's relative privilege afforded him an education that set him on a path no one of African descent had yet blazed in early modern Europe. It's unclear exactly when he arrived in France—he finished medical school in 1792—but it is clear that his timing coincided with seismic changes in French colonial and race relations. Since the late middle ages, France officially maintained a Free Soil policy. In theory, anyone who set foot in France was free within its borders. However, as colonists began bringing their slaves along to mainland France, the French began to feel a bit uneasy. As the 18th century advanced, so too did laws restricting people of color. Those of 1716 and 1738 found a Free Soil loophole to deny slaves freedom. These efforts culminated in a law of 1777, which banned not simply slaves from France, but all people of color. Upon arrival, the newly established Police des noirs was tasked with confining them to designated depots and returning them to their colonial homes. But in 1791—the year of the Haitian Revolution, and apparently around the time the Fournier-Pescay family arrived in France—the Free Soil policy was reestablished for the mainland (even as slavery was effectively legalized in the colonies). And so Fournier-Pescay found himself in a country that had only just opened the doors of opportunity to people of color. ¶ This copy in a Sammelband and bound after three additional medical works: Giovanni Girolamo's Italian translation of Pierre-Joseph Desault's Traité des maladies des voie urinaires (Lezioni sopra le malattie delle vie urinarie; Pavia: Baldassare Comini, [between 1791 and 1808]; 205, [3] p.; [A]^8 B-N^8) --- Jacques-Louis Nauche's Nouvelles recherches sur les rétentions d'urine (3rd ed.; Paris: Croullebois, et al., 1806; [4], 142 p.; pi^2 1-6^8 7^8(-8?) 8-9^8) --- Antonio Scarpa's Memoria chirurgica sui piedi torti congeniti dei fanciulli e sulla maniera di correggere questa deformità (2nd ed; Pavia: Baldassare Comini, 1806; 72, [4], 73-88 p. + V folded plates; [A]^8 B-D^8 E^10 F^4). ¶ A magnificent testament to social progress in the Atlantic world. Despite a fairly prodigious output, much of Fournier-Pescay's work remains thinly held in North America and is conspicuously absent from the auction record. We find at auction only a copy of Die gesammte Fieberlehre sold in 2007; a few sale records for the massive 60-volume Dictionnaire des sciences medicales (1812-1822), to which he contributed a handful of articles; and the same for Michaud's similarly voluminous Biographie universelle (1811-), to which he likewise contributed. We find no auction records of Tétanos traumatique, and we find only five copies in North America (Yale's Harvey Cushing Library, Harvard's Countway Library, NLM, Washington University, and McGill University).

PROVENANCE: Contemporary ownership inscription on a front fly-leaf, with a handwritten table of contents for the four items here bound together.

CONDITION: Contemporary marbled leather—not quite a tree pattern, but perhaps a tall shrub—and the spine simply gold-tooled in a neoclassical manner; edges stained red; marbled endpapers. ¶ A few marginal tears in the first work, and one in plate IV, none affecting content; plate III a bit soiled; foxed throughout, but the first work generally much brighter. Surface skinning to the leather in a few spots; spine generally rubbed and its title label lost; extremities worn, but not too badly. A nice, solid copy in a contemporary binding.

REFERENCES: Robert Fikes, Jr., "François Fournier de Pescay: The Unheralded Precursor of the Modern Black Physician," Journal of the National Medical Association 77.9 (1985), p. 683-686; Hans Werner Debrunner, Presence and Prestige: Africans in Europe (Basel, 1979), p. 133-134 (brief bio-bibliography; "François Fournier acheived recognition for his professional, diplomatic and scientific activity"); Biographie universelle ancienne et moderne (Paris, 1855), v. 13, p. 556-557 (pretty comprehensive bio-bibliography; born to a family in St. Domingue, "within which, as we saw from his color, African blood was mixed with that of the colony"); Shelby T. McCloy, The Negro in France (Univ of Kentucky, 1961), p. 100 (brief bio, largely drawing on the Biographie universelle); Henri Vanhulst, "Le mensuel 'L'esprit des journaux' et les débuts de la critique musicale à Bruxelles," Revue belge de musicologie 66 (2012), p. 63 ("a doctor of Haitian origin"); Olivette Otele, African Europeans: An Untold History (2021), p. 84 ("Black people were not the only group who supposedly threatened France; dual-heritage children were not welcome either."), 86 (In 18c France, "The authorities had effectively managed to criminalise black people"); Frédéric Regent, “Préjugé de couleur, esclavage et citoyennetés dans les colonies françaises (1789-1848),” La Révolution française: Cahiers de l’Institut d’histoire de la Révolution française 9 (2015), p. 16 (“Slavery, which in principle did not exist on French soil under the Ancien Régime, was abolished by the decree of 28 September 1791…The colonies, being placed outside the scope of the constitution, were not affected by this measure”); James T. Kloppenberg, Toward Democracy: The Struggle for Self-Rule in European and American Thought (Oxford Univ, 2016), p. 514 (“On September 28, 1791, it [France’s National Assembly] voted to outlaw slavery in France, where there were few slaves to free, and began inching toward granting rights to free blacks in the Caribbean”)

Item #834