Silver fittings likely made from melted alms

Silver fittings likely made from melted alms

Missale Romanum

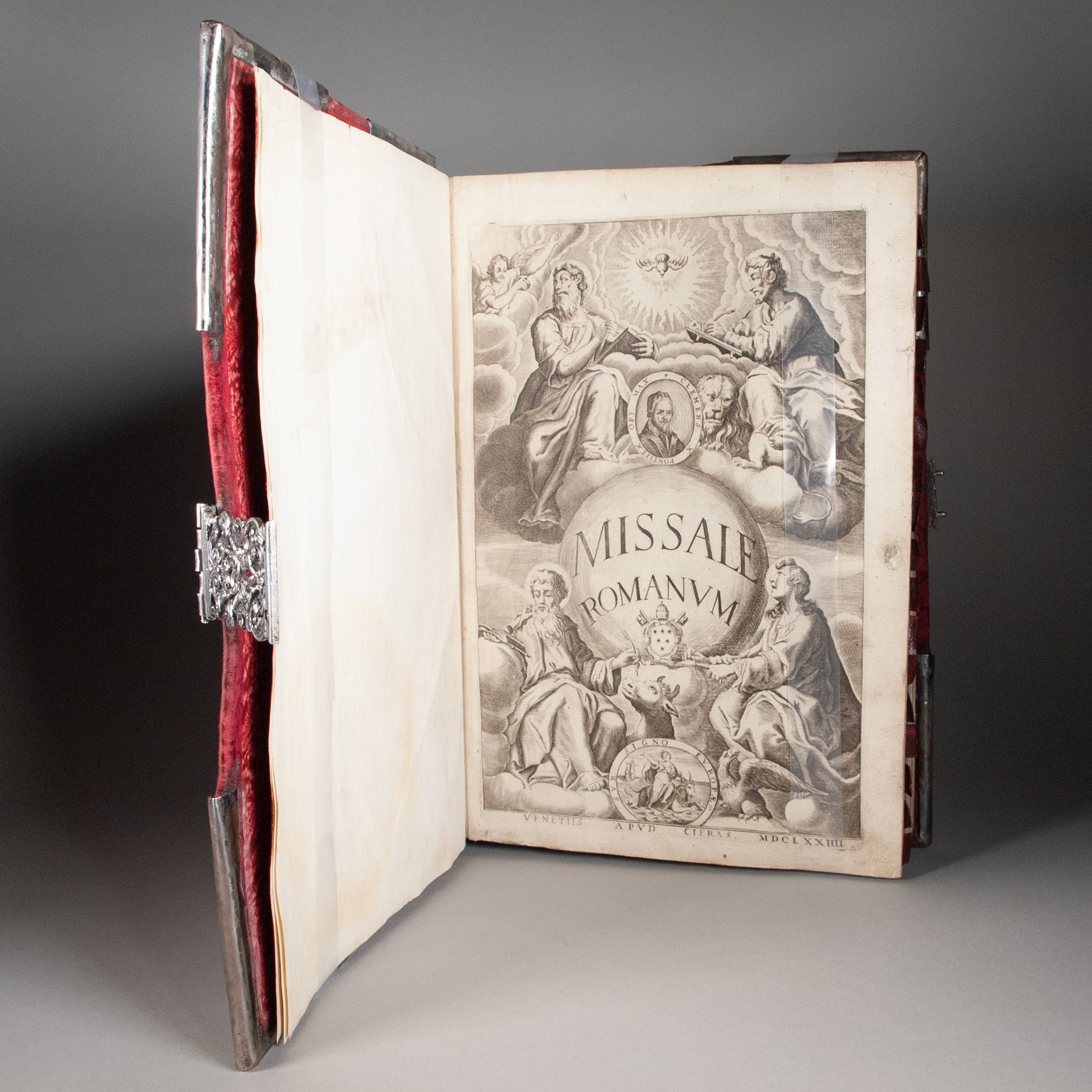

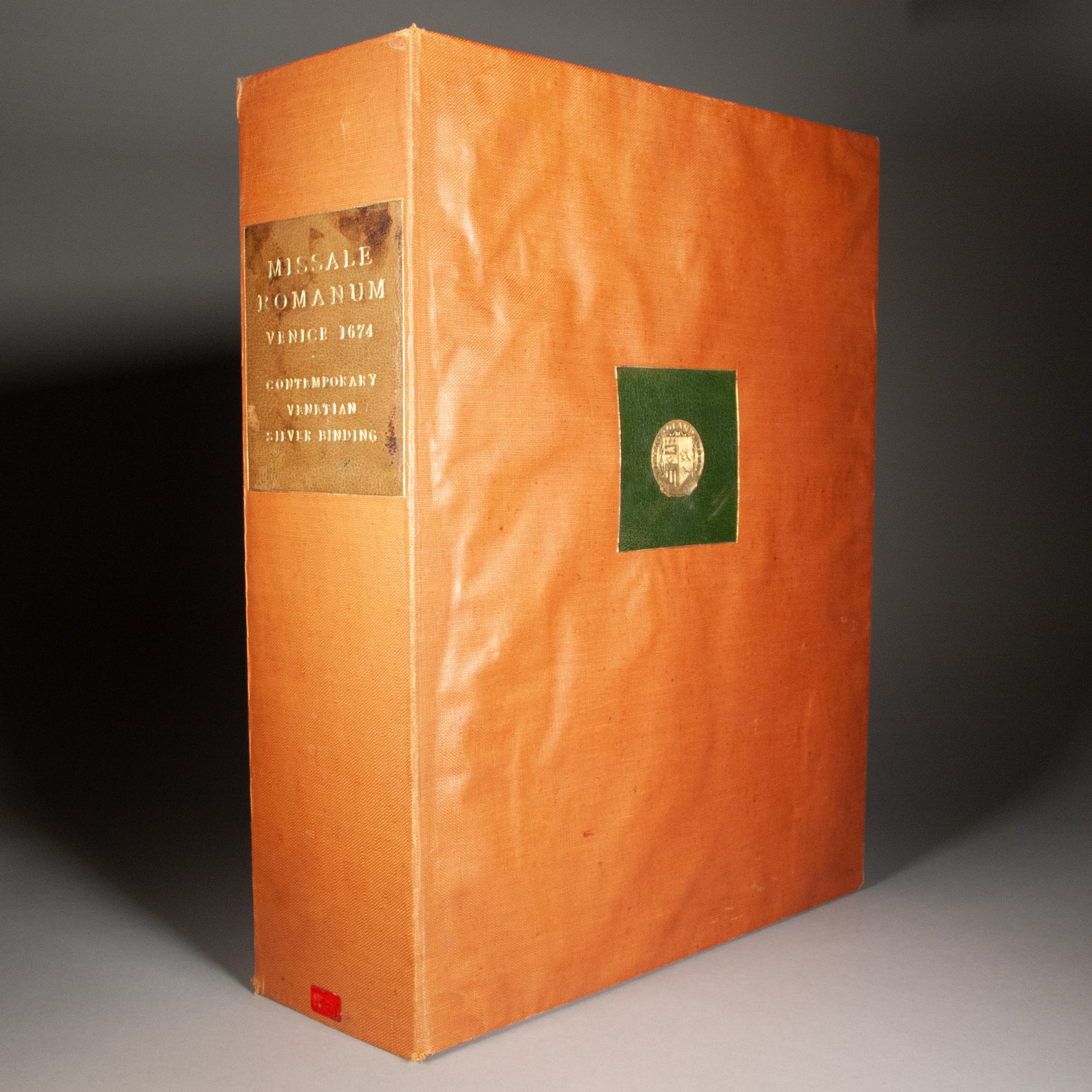

Venice: Heirs of Bonifacio Ciera, 1674

467, [1], lxxxviij, [4]; 2; 2; 4; 6, 9-28, [2]; [12] p. | Folio | [maltese cross]^10 2[maltese cross]^10 A-2E^8 2F^6 2G^4 a-e^8 f^6; A1; chi1; ^2; pi1 1-7^2 2^2; pi^2 ^2 C^2 | 365 x 257 mm

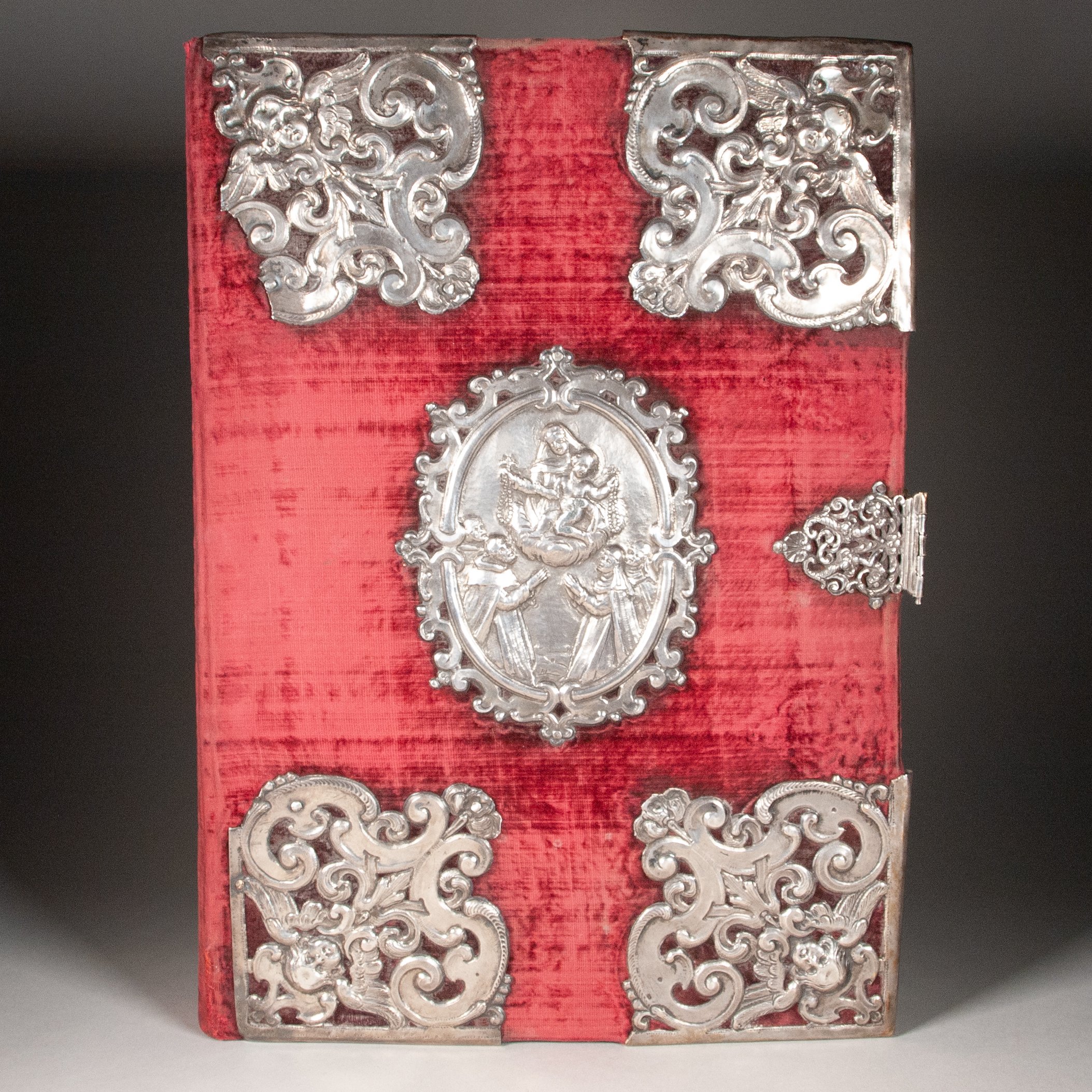

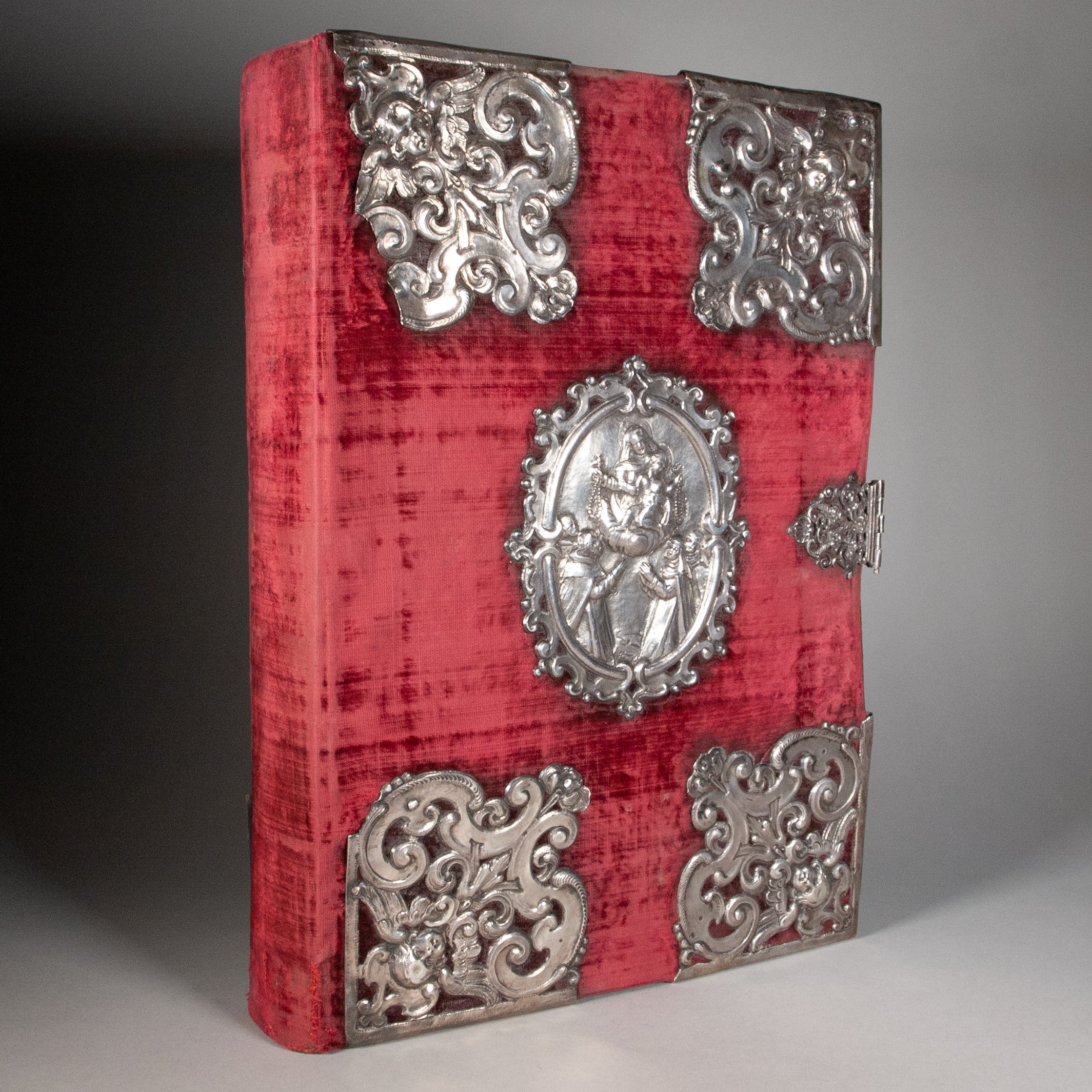

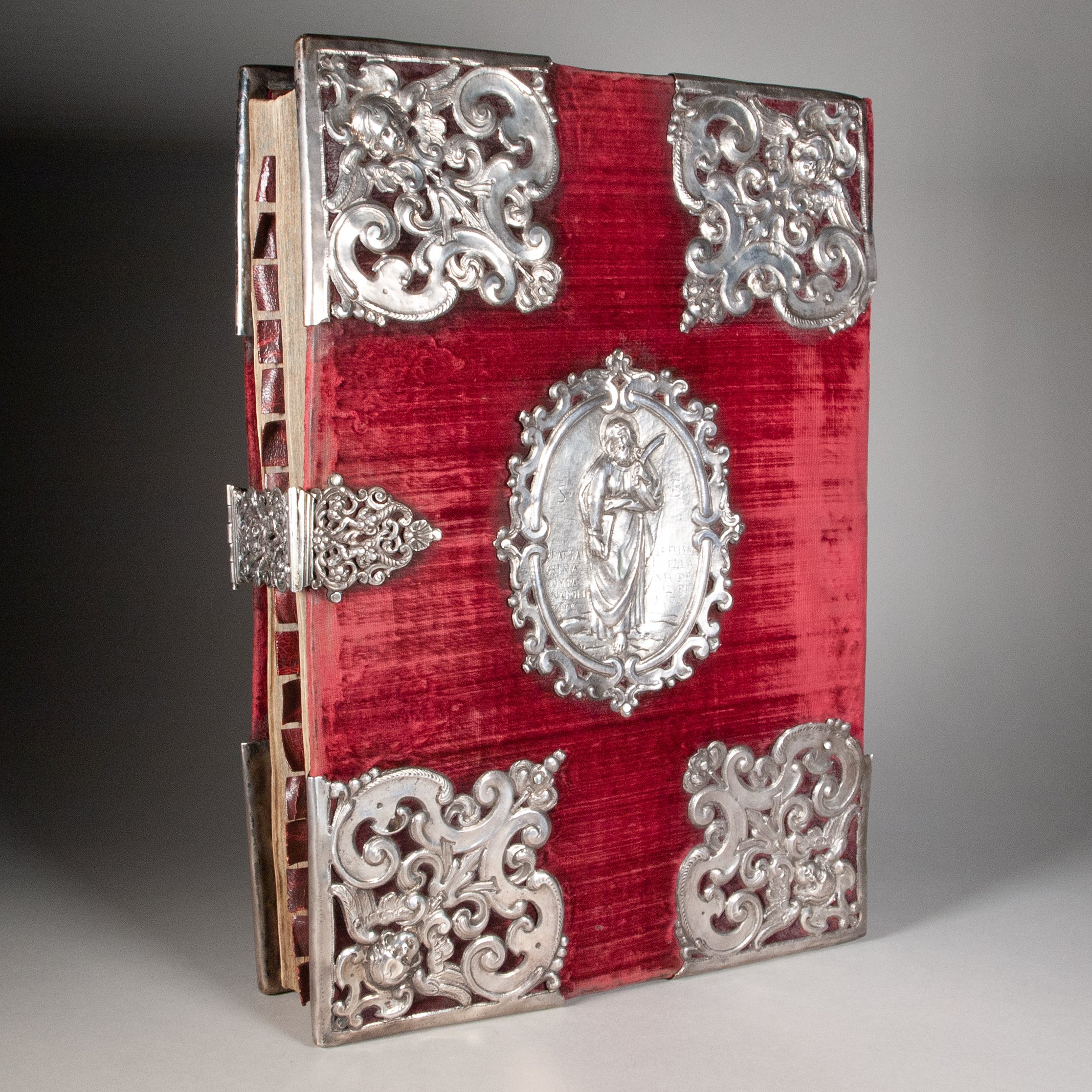

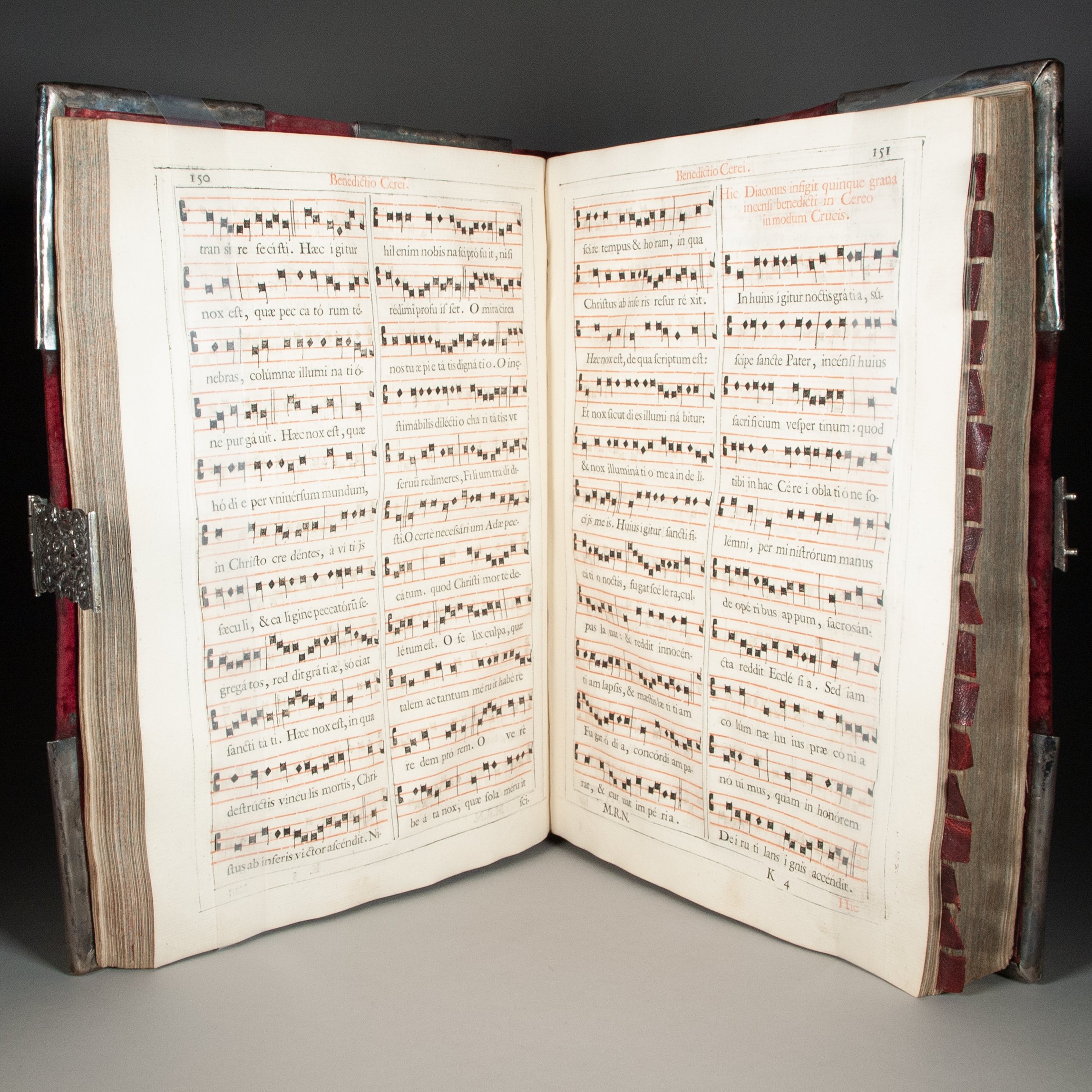

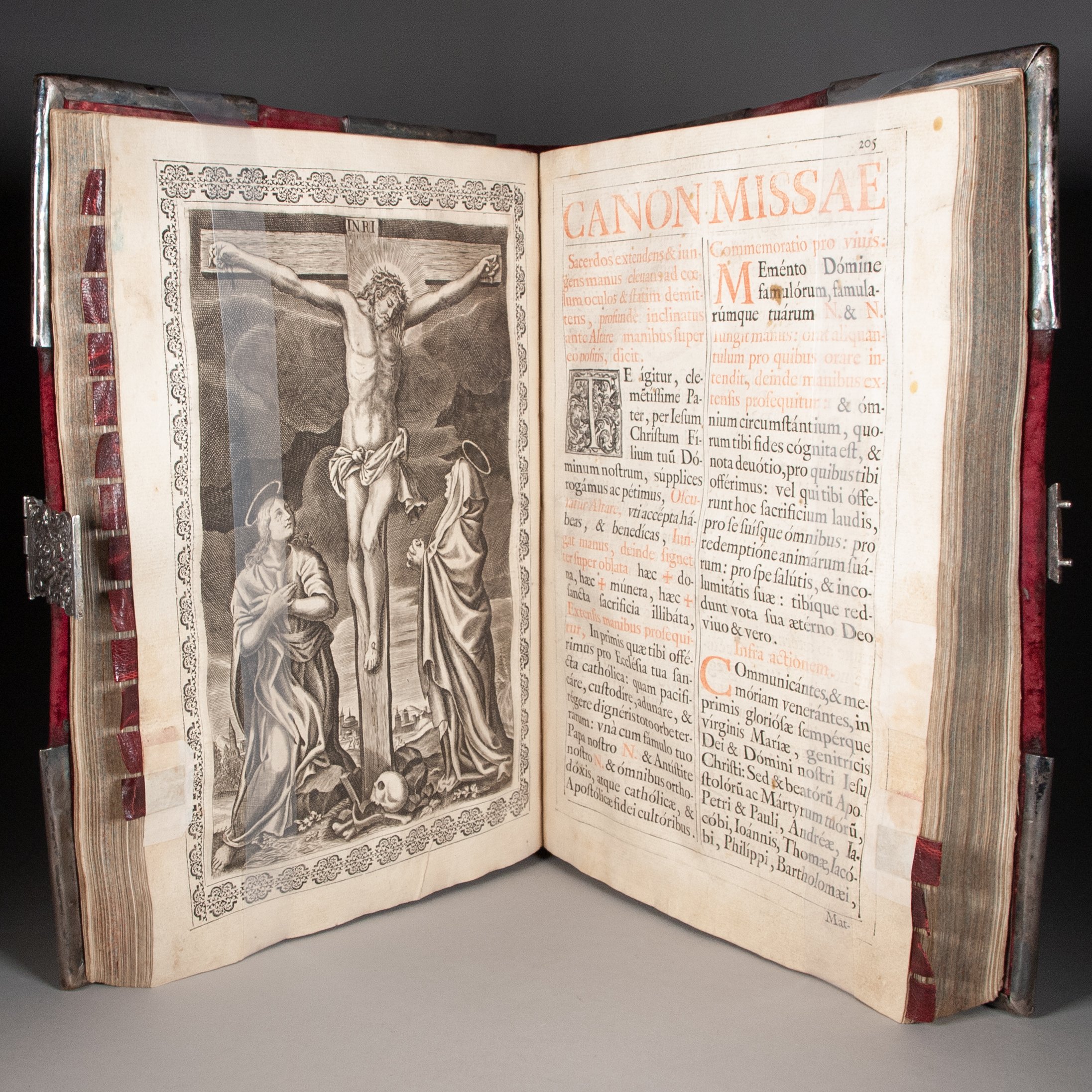

A monumental Roman Missal, here in the edition approved by Pius V in 1570, and incorporating the revisions of Popes Clement VIII and Urban VIII in 1604 and 1634, respectively. The missal was a ubiquitous liturgical genre, found in any Catholic church, and contained everything a priest needed to celebrate Mass. These were invariably large, expensive books, often very finely bound, conditions which must have fostered a strong motivation to maintain their utility as long as possible. So it's not unusual, as here, to find additional texts added over the years to meet a parish's evolving needs. Our demonstrate WELL OVER A CENTURY OF USE: a mass for St. Ignatius of Loyola (Rome: Ciera, 1676); a mass for St. Cajetan, dated 1674; a mass for the Seven Sorrows of Mary (Venice: Ciera, 1675); a mass for the Proper of Saints (Como: Pasquale Ostinelli, 1810); and another mass for the Proper of Saints, this one specifically for the Diocese of Como, also from Ostinelli's press. ¶ No doubt you're distracted by the arresting binding, contemporary crimson velvet over wooden boards, with baroque silver cornerpieces, centerpieces, and clasp, all presumably Italian work (though models for the silver mounts could well be from elsewhere). The centerpiece on the front board depicts the Virgin and Child on a cloud, each clutching a rosary, floating above men and women in worship. Though striking, we'd hardly call the design original. See, for example, Hayward’s No. VI (also #17 in the 1985 Sotheby's sale), another from Abbey's collection, on an Antwerp missal of 1649, likewise in red velvet with arabesque silver mounts featuring cherubim at the corners. Original or not, the work is exemplary. “The goldsmith who was required to produce a Missal cover was confronted with quite a different problem from that of his northern contemporary who made a cover for a Bible or prayer-book. The Missal was meant to be seen from a distance and the ornament is, therefore, embossed in fairly high relief” (Hayward). ¶ As a luxury covering material for books, the use of velvet dates to the Middle Ages, though its fragility has done its survival rate few favors. The fabric was difficult to work with, laborious to make, and typically more expensive than leather. Even in the late 18th century, it was usually reserved for public-facing service books (like missals) and high-end bindings for personal books (especially as a base for embroidered bindings). And obviously covering it in silver added a great deal of richness. For the less pecunious parishioners who worked outside the book trade, their church’s missal must have been one of few exposures to luxury bookbinding. ¶ An inscription on the rear centerpiece notes the binding was made from the alms of a Naples organization: Fatta de ellemosina della Compagnia de Napoli a 12 di 7bre 1676, preceded by initials SB, flanking a likeness of St. Boniface holding a book and a sword. Beyond having been simply financed by said alms, there's good reason to read the inscription more literally—fatta coming from fare, to do or to make. "The purchase of silverware went something like this. A customer went to the cashier [kashouder] and gave him, say, ten silver guilders. These had to be melted down [omgesmolten] to make book clasps [boeksloten], for example. The buyer then added—to name just one amount—a guilder for production" (van Noordwijk). Which is to say, CUSTOMERS COMMONLY PROVIDED THEIR OWN SILVER COIN TO BE MELTED DOWN AND REWORKED INTO BOOK FITTINGS, and we expect that was the case here. While the practice might have been typical, language suggesting the possibility on bindings themselves is anything but. ¶ An exceptional binding, with AN INSCRIPTION THAT EVOKES THE PRODUCTION METHOD BEHIND EARLY MODERN SILVER BOOK FITTINGS. We find no copies of this edition in WorldCat.

PROVENANCE: The unspecified Naples compagnia responsible for this binding was likely a local confraternity, though venturing further seems rather hazardous given the generic language. If forced to suggest something, we might offer the Confraternity of the Holy Rosary, a sprawling Dominican organization for lay religious. We base our speculation only on the front centerpiece, in which Mary and Jesus each hold a rosary above a group of men and women. The Confraternity of the Holy Rosary was famously coed, though certainly not the only confraternity that admitted both sexes. The collection of alms was a common activity among those sodalities. Such money might typically have been spent on more traditional relief for the needy, though liturgical books do have their own history of donation. By way of Italian precedent, Lucrezia Tornabuoni, who married into the Medici family, commissioned an illuminated missal in the 15th century for a church. And we've handled a 1738 Venice missal, likewise in red velvet and silver fittings, that was likely a collaborative donation commissioned by four women. “Motivated by the desire for salvation patrons initiated the process, hiring artists and architects to build and decorate churches and provide the liturgical apparatus central to religious practice” (ffoliott). And certainly the missal ranks among the indispensable pieces of liturgical apparatus for any church. Given the additions for the Diocese of Como, we expect the book eventually, if not immediately, found its way to a church in that area. ¶ From the library of John Roland Abbey, THE MOST CELEBRATED COLLECTOR OF SILVER BINDINGS, with his bookplate on the front paste-down and his gilt-stamped leather label on the front cover of the box. Armorial embossed stamp of Detlef M. Noack (1925-2014), professor at Berlin's University of the Arts, on one of the newer front fly-leaves, with a small trove of documents recording his acquisition from Martin Breslauer on 7 August 1995.

CONDITION: Contemporary velvet and silver as described above; seventeen leather index tabs at fore-edge around the Canon of the Mass. Title page is engraved; register and colophon on final page, this copy complete per the register, with additions noted above. Printed in red and black throughout, with notated music, many decorative initials, and full-page engravings facing p. 17, 205, 215, and i. Housed in a custom cloth clamshell box, well padded on the inside. ¶ Scattered leaves rather soiled, with occasional wax drops, these sections clearly well used; Canon of the Mass with some tears, occasionally affecting content (Crucifixion image included), some of these repaired; Canon also quite soiled; tear in upper margin of Q3, affecting text; margins of Q4-5 reinforced; a handful of other small marginal tears, some of them repaired, occasionally affecting a few lines of text; faint odor of cigarette smoke. Recased, adding new fly-leaves and red paste-paper endpapers; the single clasp was at one point relocated to the middle of the fore-edge, likely making up for two incomplete clasps (subtle evidence in the velvet betrays the clasps' old locations); about a square inch of loss to the silver fitting in the upper left corner of the front board; paper at the front hinge worn through in spots, but the joint remains strong, with only a little play; pile worn away from much of the velvet, but with only a handful of small tears in the fabric itself, all at the foot of the spine and all neatly repaired. Box worn at the extremities, and its cloth on the front cover a bit cockled.

REFERENCES: Silver and Enamel Bindings (Sotheby's, 10 May 1985), #34 (this copy; "Italian, Naples, probably c. 1676") ¶ Bernard van Noordwijk, De erfenis van Kortjakje: 250 jaar boekjes vol zilverwerk (2009), p. 19 (cited above; silversmiths at the time, at least in Holland, would commonly have promotional display case, which could include book fittings alongside buckles, flatware, and just about anything else that might be made from silver); Nancy Quam-Wickham, "Silversmith," A Day in the Life of an American Worker: 200 Trades and Professions through History (2019), unpaginated ebook (on colonial American practice: "A client desiring to protect his or her wealth in silver products brought silver coins to the workshop, where the silversmith first melted the coins into ingots, or skillets, which could then be shaped into platework"); Sheila ffolliott, “European Women Patrons of Art and Architecture, c. 1500-1650: Some Patterns,” Renaessance Forum 4 (2008), p. [1] (cited above); Stefanie Solum, “The Problem of Female Patronage in Fifteenth-Century Florence,” The Art Bulletin 90.1 (March 2008), p. 80 (on Tornabuoni’s missal); J.F. Hayward, "Silver Bindings from the Abbey Collection,” Connoisseur 130 (Oct 1952), p. 102 ("The goldsmith was not expected to design his own decorative compositions, but copied them faithfully from a pattern-book or some other printed source"), 103 (cited above; "Relief ornament on the earlier bindings was usually cast and applied rather than embossed, but by the second half of the Seventeenth Century, the latter method was employed"), 104 ("There are no great names in the history of silver bindings; with very few exceptions the artists or craftsmen who produced them are anonymous."); Maria Hayward, Rich Apparel (Ashgate, 2009), p. 125 (on the relative value of velvet); Christopher F. Black, Italian Confraternities in the Sixteenth Century (Cambridge University, 1989), p. 36 ("more positive and egalitarian attitudes to women in mixed confraternities are found" in Rome and Lombardy), 38 (while coed confraternities were not unusual, those with more women than men were, "except possibly among Rosary devotional confraternities, which might be seen as essentially feminine societies," and appear to have treated women members with greater equity)

Item #800